The Baby Maker movie storyline. Tish Gray (Barbara Hershey), a California hippie, is introduced to Suzanne and Jay Wilcox, a wealthy Beverly Hills couple who are unable to have a child. They offer Tish a considerable sum of money if she will conceive and bear a child by Jay. Tish, who enjoys being pregnant, agrees to the scheme, and she and Jay go to his cabin in the mountains; shortly after returning to Los Angeles, Tish learns that she is pregnant. Suzanne, who is eager to have the child, makes Tish promise to give up her hippie way of life and the use of drugs.

Tension begins to mount between Tish and her boyfriend, Tad Jacks, and after an argument she leaves him and moves into the Wilcox home. Although the household seems peaceful, Jay’s feelings for Tish grow stronger while Tish becomes resentful of Tad’s infidelity and has doubts about giving up the child to a middle-class family. Furthermore, she is berated by her friend Charlotte for accepting such a lifestyle, but their friendship resumes when Tish agrees to go to a demonstration against war toys. When Tish bears the long-awaited child, the Wilcoxes pay her the balance of the money, take the child, and bid her farewell.

The Baby Maker is a 1970 American drama film directed and co-written by James Bridges and released by National General Pictures. Emmy-winner and Oscar-nominee Barbara Hershey (“Portrait of a Lady,” “Hannah and Her Sisters”) plays a free spirit who agrees to bear a child for a childless couple in this early look at the phenomenon of surrogate motherhood. Co-starring Scott Glenn (“The Silence of the Lambs,” “The Right Stuff”), this is the first feature by director James Bridges (“Urban Cowboy,” “The China Syndrome”).

Film Review for Baby Maker

The current Chicago Seed contains a devastating attack on “The Baby Maker” by Penny (nobody at the Seed has a last name except its lawyer), and it’s a review I really enjoyed reading. After Penny’s finished with “The Baby Maker” it stands exposed as a haven of middle-class values, male chauvinism, political naivete and phony hipness.

Penny’s critical strategy is the deadpan plot synopsis, an especially effective tactic because it appears to be objective. Actually, you can get quite subjective in a plot synopsis by carefully selecting what you tell and don’t tell. You’ve also got to adopt a certain conspiratorial tone in your language.

I mention Penny’s review, first, because I liked the writing; second, because “The Baby Maker” is terribly vulnerable to her approach. A movie about a middle-class couple hiring a hippie chick to have their baby because the wife is sterile, indeed!

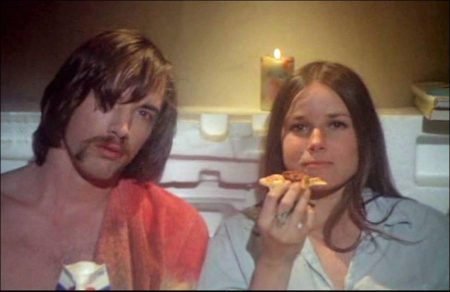

And yet “The Baby Maker” will appeal to many audiences, I think, because it’s fundamentally civilized, and funny, and stunningly well-acted. Too often in these days of being compulsively with it, people avoid movies they might like to see, because they’re afraid it would be unhip to be seen at such a movie. It’s also unhip, I suppose, to have an emotional reaction to scenes like the natural childbirth in “The Baby Maker,” and yet that scene of 10 or 12 minutes was as beautiful, as transcendently humanistic, as anything I’ve seen in a movie in a long time.

Like a lot of movies these days, “The Baby Maker” exists more in its individual scenes than as a whole. There are bad lapses of tone, as when the girl throws paint on her former boyfriend, or when the wife embarrassingly slips her wedding ring onto the girl’s finger before the baby making commences.

And yet against that you can balance a scene where people are picketing against war toys, and you think for a moment the scene has collapsed into banality, and then it surprises you with a hilarious switch in tone. Or, most stunningly, the childbirth scene, played so luminously by Barbara Hershey that there are tears in the audience, and that’s unusual because they’re tears of joy, not sorrow.

The movie has to be taken, I think, as a comedy of manners. The husband (Sam Groom, with the easy attractiveness of a young James Stewart) and his wife (Collin Wilcox-Horne) are, indeed, middle class. But part of the movie’s humor comes from playing the middle class against itself. The girl notes that the couple has all the Frank Sinatra albums. “Yes,” the husband says, “but we have all the Beatles albums, too.”

Well of course the Beatles are maybe two years beyond being contemporary, but the movie knows that and that’s why the dialog works with a sort of sly understatement. Later, when the husband promises the girl that the baby will have “all the Dylan albums,” you appreciate this sort of understatement; quiet irony is rare these days.

I obviously like “The Baby Maker” more than I suspect a lot of people will. But let me say it’s a movie you won’t find painful to experience, even if you don’t like it. And if you do like it, if you’re willing to grant the necessary suspension of disbelief, “The Baby Maker” may begin to really get to you. Sure, the ad campaign is raunchy. Sure, the wife seems a little too neurotic even for the demands of the character. But a moment’s thought on the plot of “The Baby Maker” may suggest what errors of taste it might have committed. It could have been awful, but it’s actually pretty good.

The Baby Maker (1970)

Directed by: James Bridges

Starring: Barbara Hershey, Scott Glenn, Collin Wilcox-Horne, Sam Groom, Scott Glenn, Jeannie Berlin, Lili Valenty, Helena Kallianiotes, Phyllis Coates, Madge Kennedy, Ray Hemphill, Bobby Pickett, Paul Linke

Screenplay by: James Bridges

Production Design by:

Cinematography by: Charles Rosher Jr.

Film Editing by: Walter Thompson

Set Decoration by: Raymond Paul

Makeup Department: Sugar Blymyer, Wes Dawn

Music by: Fred Karlin

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: National General Pictures

Release Date: October 1, 1970

Views: 263