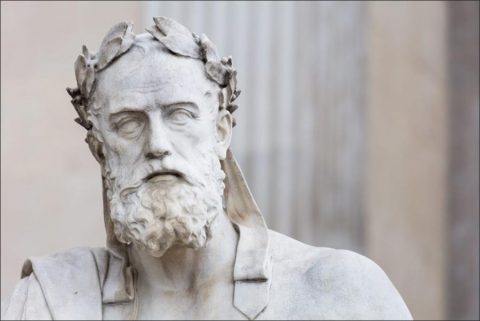

Xenophon was an Athenian born about 425 B.C. He was taught by Prodicus, then by Socrates, whose personality and ethical views made a lasting impression. In 401 Xenophon joined the expedition which Cyrus was preparing against his brother Artaxerxes, king of Persia. After the battle of Cunaxa the Greek contingent found themselves surrounded by enemies in the heart of the Persian Empire, and their generals murdered.

Xenophon helped to lead them through hostile savages, mountains, and snow-drifts to the Black Sea and so at length to safety. Later he accompanied the great Spartan, Agesilaus, on his Asiatic campaigns, returned with him, and fought in the Spartan army at Coronea ( 394) against Thebes and Athens. Being exiled from Athens, he received from the Spartans an estate at Scillus in Elis, where he lived for some twenty years engaged infield-sports and literary composition. He died about 350 B.C.

His works are not only interesting as literature and full of information; they reveal also a charming and versatile character. His adventurous many-sided life had three great interests: philosophy, war, and manly sports; it was dominated by two great personalities–Socrates and Agesilaus.

The philosophic writings give us a picture of Socrates which is a necessary complement to ‘the more imaginative work of Plato. It has been said that the latter corresponds to the Fourth Gospel, the former to St. Mark’s. And there is a story which resembles the calling of certain Apostles. One day Socrates met him in the street and inquired where one could buy this and that.

Xenophon told him. ‘And where must one go to become a good man?’ The youth could not answer. ‘Follow me,’ said Socrates, ‘and I will show you.’ The lessons which Xenophon learned were practical, the love of virtue, fairness of mind, sagacity. His Apology explains why Socrates did not fear death. The Memorabilia are a record of the Master’s conversations, designed to show the Athenians how innocent Socrates was of the charges which led to his execution.

Xenophon shows here some of Boswell’s merits: he reports the Master’s conversations with a minimum of comment and so conveys to us a personality splendidly vigorous and in love with virtue and common sense. But, had we no other account, Socrates would be almost forgotten to-day. The Symposium depicts Socrates at a drinking-party and ends with a charming naive account of a little play between Dionysus and Ariadne. In the Oeconomicus we read an account of household management given by one Ischomachus: ‘What a beautiful sight when shoes are arranged according to their kinds, and clothes properly sorted!’. The most interesting passage is Ischomachus’s training of his girl-wife.

A tract on Revenues recommends the development of the Athenian mines. Hiero is a dialogue between that great Syracusan ruler and the poet Simonides on the business of a ‘ tyrant’. The Polity of Sparta describes the Lacedaemonian organization admiringly but (if the passage is genuine) laments present-day degeneracy. In the famous Education of Cyrus is an ideal picture of Cyrus the Great and the development of an imaginary state. The Constitution of Athens is an important little treatise wrongly ascribed to Xenophon; it was written about 420, apparently by an oligarchic Athenian, and describes the democracy of Athens with hostility and insight. Hunting, Horsemanship, and the Commander of Cavalry are three practical handbooks.

Xenophon’s historical ‘works are the most important. Agesilaus is a biography of the great soldier who narrowly missed anticipating the conquests of Alexander. The Hellenica are a continuation of Thucydides, valuable for what they tell, but untrustworthy in so far as they omit or minimize: Xenophon’s devotion to Sparta has led him to whittle down, or fail to see, the importance of Epaminondas and the foundation of Megalopolis.

The first two books are the best, and his description of the coming of the news from Aegospotami is famous. ‘At Athens the tidings were announced when the Paralus arrived at nightfall, and the wailing passed up the Long Walls to the City as one passed the news to another. That night no one slept. They mourned not only the dead but themselves far more, expecting to suffer the doom they had inflicted upon Melos, the Spartan colony, and Histiaea, Scione, Torone, Aegina, and many other Greek towns’.

The Anabasis, one of the best-known and best-loved books in Greek, describes first the expedition ‘proper, and then (in six of the seven books) the retreat of the ten thousand Greek mercenaries after Cunaxa through the Persian Empire to the Greek cities on the Black Sea and so to Thrace. It is a story filled with peril, courage, and resourcefulness, relieved by many personal notes and picturesque details–the miseries of frostbite and snowblindness, the Mossynoeci whose children throve so well on chestnuts and pickled dolphin that they were ‘nearly as wide as tall’, the tempting expanse being entirely tattooed, and a wealth of quaint or courageous feats. The most celebrated passage describes the climax upon the summit of Mount Theches.

‘A great clamour arose. Xenophon and the rearguard imagined that new enemies were attacking in front… but as the shouting grew louder and nearer, and each party as it came to the top began to run towards those who took up the shouting, and the volume of clamour kept growing as more arrived, it struck Xenophon that something peculiar was afoot. Mounting his horse he took Lycius and the cavalry and galloped forward. In a few moments they heard the soldiers shouting “The Sea! the Sea!” and passing the word along. At this every man began to run, even the rearguard; the mules and horses were put to the trot. When all had reached the summit, in that moment they embraced one another, their generals and their captains, weeping’. Xenophon is no genius, but it is precisely because of this that he provides the finest example of what the Greek world could provide as a truly liberal education.

Visits: 330