The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR, or Soviet Union, was a communist state from 1922 to 1991 and was a big rival of the US from World War II to the end of the ’80s. But what was the Soviet Union really like? And what was it like living there?

Well, it turns out, it’s complicated. So today, we’re going to take a look at things you didn’t know about daily life in the Soviet Union. OK, you don’t know how lucky you are that we’re going to tell you how things worked back in the USSR.

From the late ’40s to the early ’60s, the Soviet Union had a counterculture group that aped Western beatnik and hipster culture and even made bootleg Lps. This being the USSR, the so-called Stilyagi, or style hunters, were forced to make the bootlegs out of recycled X-ray films.

This meant the records had ghostly bones all over them, which, to be honest, sounds pretty badass. The Stilyagi were, in the words of one style blogger, “a group of dandy youngsters dressed up in colorful American-inspired get-ups that were unafraid to make a bold fashion statement.”

McDonalds, Coca Cola and Pepsi

McDonald’s and Coca-Cola are often cited as being the two American companies with the most worldwide influence and reach. But it was actually Pepsi Cola that made it into the USSR first. Yeah, Pepsi was available in the Soviet Union a full 21 years before McDonald’s and 16 years before Coca-Cola. It had a lot to do with Pepsi’s appearance at an exhibit at Moscow’s Sokolniki Park in 1959, where the soda was given out for free in disposable paper cups.

The Soviets struck a deal with Pepsi a decade later that also included the distribution rights for Stoli vodka. Despite the headstart, however, Coke would catch up. And as of 2020, Coca-Cola was the most popular non-alcoholic beverage in Russia. Pepsi was second. ut speaking of beverages, famous beer lovers like Homer Simpson and Norm Peterson might have loved Russia because while this sounds wild, it wouldn’t be until 2011 that beer came to be defined as an alcoholic beverage in the former Soviet nation.

Prior to that, legislation classified it as a foodstuff, meaning it could be sold like a soft drink. This meant it could be sold in street kiosks and could be imbibed openly in just about any public place in the country. Now to be clear, this wasn’t because the Russians didn’t know beer was alcoholic or anything like that. It was really a legal consequence of an international trade pact known as the Nice Agreement. The agreement classified hard liquor and beer as two different types of goods, something Russian liquor producers spent years trying to change without success.

In any case, alcohol in general was wildly popular during the Soviet era. In fact, when Mikhail Gorbachev, the country’s head of state from 1990 through 1991, tried to pass a dry law that raised the price of booze and restricted when and what quantities it could be sold, affected his popularity. Some historians think it even hastened his downfall. Studies have shown that Gorbachev’s program correlated with a rise in life expectancy and a drop in criminal behavior. On the other hand, it cost the country about 100 billion rubles in tax revenues and became a massive source of income to organized criminals and black marketeers. So it was a mixed bag, or a mixed drink in this case.

In an era when everything is made to be constantly replaced and upgraded, it’s hard to remember that there was once a time when things were built to last, like for example, Soviet cars. According to Russian author Alexander Kabakov, from the 1930s to the 1950s especially, car owners in the Soviet Union took great pride in making their vehicles last as long as possible. And in some cases, they lasted a lifetime.

It wasn’t just careful owners that gave these vehicles their longevity. Quality control on the manufacturing end was a huge part of it and so was build quality. In fact, Kabakov says the metal frames were so thick coming off the line, they were basically resistant to corrosion.

Food in Soviet Union

Everyone’s heard of long Soviet bread lines, but that’s not even the half of it. Even as self-proclaimed well-off American student living in Moscow in the mid ’60s said that getting any food at all was a tremendous chore. According to Dr. Naomi F. Collins, she was constantly in a state of exhaustion just from the efforts of daily living. Even buying staples like cheese and rice took forever because you had to stand in long lines for nearly every item you wanted. And even after waiting, you didn’t get the item directly. You had to get vouchers at each station and pay a cashier before going back to the stations and picking up your items.

Kitchen Politics

Soviet authorities in Stalin’s time considered private kitchens, dining rooms, and even apartments to be dangerous to the regime. So an idea was tossed around in the early days to force people to eat in communal cafeterias. It sounds like a storyline from a Dr. Strangelove type political farce. But so-called kitchen politics were actually considered such a threat that Soviet leaders wanted houses built without kitchens at all. It wasn’t just about preventing people from having privacy.

The idea was also meant to relieve a housewife from her daily chores so that should develop as a personality and free the country from the tsarism and bring happiness to poorer classes because I guess we all know cooking only brings sorrow. Not surprisingly, the idea did not pan out. And soon, widespread industrialization led to over 100 different ethnic groups all being served the same exact meals, such as canned soup, meat, and fish.

Poverty

A New York Times feature from 1989 reveals quite a bit about the Soviet attitude regarding the poor and the homeless in the last few years of the USSR. One Western diplomat is quoted as saying that Soviet officials stopped gathering statistics on poverty because they insisted it simply did not exist. When presented with the idea of combating the issue with American style soup kitchens, one Soviet official even said, we are opposed to this system where poor people get free dinner.

Psychologically, it’s a strange idea to us. We will not consider such a variant. They probably should have considered such a variant, however, since the state of the Soviet economy made earning one’s dinner incredibly difficult. In fact, in 1989, it took a Soviet worker 10 times longer to earn a pound of meat than it did the average American. But not everyone was having a hard time getting the foods they wanted.

Kremlin Canteen

In 1984– the year, not the George Orwell novel– Konstantin M. Simis reported that despite there being a nationwide food shortage, the ruling elite in Moscow ate like kings, using the so-called Kremlyovskaya stolovaya, or Kremlin canteen. The canteen was a network of special stores that sold food of particularly high quality to those with special passes sausages, fish delicacies, cheeses, bread, vodka, cakes, as well as fruits and vegetables, produced and grown on state farms that supplied the canteen system exclusively. There were also American cigarettes, scotch whisky, English gin, and pharmacies that sold prescriptions you couldn’t find anywhere else in the country.

Antigay laws

Joseph Stalin really did not like the gay community. Soviet era documents declassified in 1993 show he personally insisted on the passage of an anti-homosexual law. He got his wish in 1933 when Article 121, which expressly prohibited male homosexuality, was added to the criminal code. Once in effect, such activity was punishable by up to five years of hard labor in prison.

Stalin wanted the law due to a report from the Soviet secret police that warned of pederast activists holding orgies and engaging in espionage. Throughout the Soviet era, being openly gay meant facing prison or even hard labor. Not only that, gay people were widely considered pedophiles and fascists and still are in parts of modern Russia where homophobia still lingers.

Stalin’s anti-gay legacy lingered into the mid-90s after the fall of the Soviet Union. Gay people in prison for sodomy didn’t even receive amnesty when the laws that put them there were repealed in 1993.

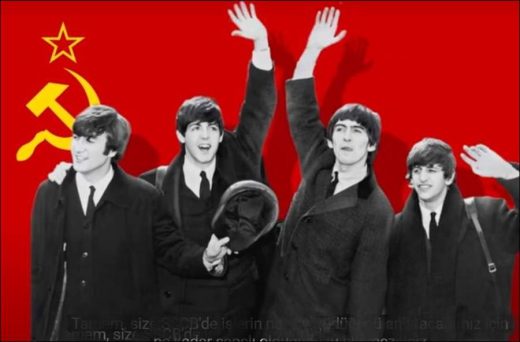

Blacklist

Facing accusations of religious obscurantism and anti-communism, heavy metal bands such as Black Sabbath, Nazareth, Iron Maiden, and Judas Priest were on a secret blacklist kept by the Soviets and distributed to party officials in 1985. It wasn’t just heavy metal that threatened the establishment, though.

Plenty of pop and indie acts made the list, too. Bands like Talking Heads, the Village People, and 10CC were listed in the document, which was written up for the purpose of intensifying control over the activities of discotheques. The translated title of the blacklist, by the way, was “the approximate list of foreign musical groups and artists whose repertoires contain ideologically harmful compositions.” It’s hard not to be amused by a totalitarian regime feeling threatened by the Village People.

It’s hard to imagine a capitalist government using its citizens to stop the production of tasteless bric a brac. But that’s exactly what the Soviets did. The Soviets apparently hated kitsch, at least in the early days.

In 1928, the state-run newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda even launched a campaign called “Down with Domestic Trash.” Why? According to the state-run newspaper, all these dogs, mermaids, figurine devils, and elephants only helped smuggle back Meshchanstvo. Meshchanstvo, for the record, is a virtually untranslatable term meaning preoccupation with every day. I wonder how they’d feel about Funko Pop figures.

Jewish people living in the Soviet Union after World War II were forced to hide matzah in pillowcases inside suitcases and transport it when visiting relatives because baking it inside synagogues was explicitly forbidden. Matzah, for those who don’t know, are the flat crackers Jews eat to commemorate Passover.

The Soviet Secret Police would patrol synagogues to enforce the rule. So Jewish families in the USSR had to get secretive themselves. It’s odd to think of making crackers as an act of rebellion, but it was. A man named Slava FRumkin who lived through it all says it was a point of pride. It was like a sense of secrecy around this. And it was filling, to some degree, with some pride your heart. You’re doing something secretly that the government doesn’t want.

Staples

Yes, the staples that held together Soviet passports were made from an inferior metal that could corrode and get rusty. This may seem like a bug, but it was actually a feature. And for secret agents trying to use fake passports, it was a huge deal.

Unlike passports in the USSR, American passports used stainless steel staples. So anyone trying to pass their fake Soviet passport off as a real one gave themselves away if they were using the wrong staples.

A Russian FSB or federal security service official told the Chicago Tribune that hundreds of American agents got caught because they didn’t know this. It’s always the little things.

Views: 229