After a commenter raised questions about the originality and authenticity of this interview, I found many similarities between the interview and the subtitled interviews included as DVD extras on the Criterion Collection DVD of “The 400 Blows” and its Antoine Doinel box set. This post has a detailed discussion of my investigation and conversations with Bert Cardullo, who presented this text as Truffaut’s last interview.

Below, I have annotated the Cardullo’s text, pointing out passages that are nearly identical or very similar to these recorded interviews, some of which are also available on YouTube. Although Cardullo’s “last interview” seems to have been pieced together rather than conducted as a conversation, many of these answers are indeed Truffaut’s and may lead some readers back to these video interviews.

Interview: Alter Ego, Autobiography, and Auteurism

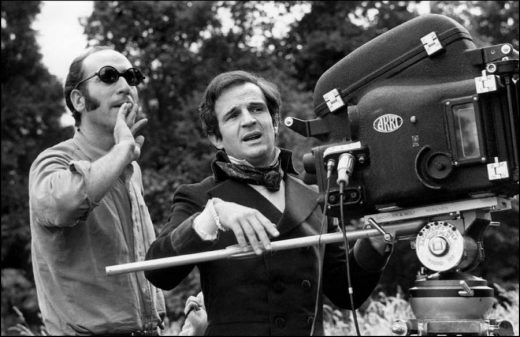

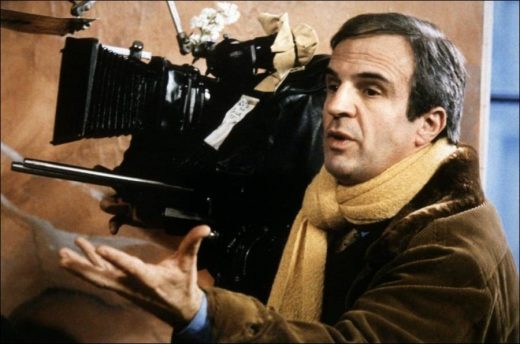

This interview was conducted both in English and French (translated by me) in late May of 1984 in François Truffaut’s private office at Les Films du Carrosse, the production company in Paris he founded and ran. His last public appearance had been in a television interview on April 13, 1984, for the “Apostrophes” series hosted by Bernard Pivot. When Truffaut generously agreed to meet with me for what was intended to be a print interview (which did not materialize at the time), he was clearly weak but unquestionably lucid. He died from brain cancer on October 21, 1984.

Bert Cardullo: I’d like to focus our discussion today on the Antoine Doinel cycle, M. Truffaut—though perhaps we’ll have time to treat some other films of yours as well. Could we begin by talking about your life prior to becoming a movie director?

François Truffaut: Yes, of course. During the war, I saw many films that made me fall in love with the cinema. I’d skip school regularly to see movies—even in the morning, in the small Parisian theaters that opened early. At first, I wasn’t sure whether I’d be a critic or a filmmaker, but I knew it would be something like that. I had thought of writing, actually, and that later on I’d be a novelist. Next I decided I’d be a film critic. Then I gradually started thinking I should make movies. And I think seeing all those films during the war was a sort of apprenticeship.

The New Wave filmmakers, you know, were often criticized for their lack of experience. This movement was made up of people with all kinds of backgrounds—including people like me who had done nothing more than write for Cahiers du cinéma and see thousands of movies. I saw some pictures fourteen or fifteen times, like Jean Renoir’s “The Rules of the Game” [1939] and “The Golden Coach” [1953]. There is a way to see films that can teach you more than working as an assistant director, without the viewing process becoming tedious or academic.

Basically, the assistant director is a guy who wants to see how movies are made, but who is constantly prevented from doing just that because he gets sent on errands while the important stuff is taking place in front of the camera. In other words, he is always required to do things that take him away from the set. But in the movie theatre, when you see a film for the tenth time or so, a film whose dialogue and music you know by heart, you start to look at how it’s made, and you learn much more than you could as an assistant director.

Which films first struck your attention when, as a boy, you began frequenting the cinema?

The first films I truly admired were French ones, like Henri-Georges Clouzot’s “The Raven” [1943] and Marcel Carné’s “The Devil’s Envoys” [1942]. These are movies I quickly wanted to see more than once. This habit of multiple viewing happened by accident, because first I would see some picture on the sly, and then my parents would say, “Let’s go to the movies tonight,” so then I’d see the same movie again, since I couldn’t say I’d already seen it. But this made me want to see films again and again—so much so that three years after the Liberation, I’d seen “The Raven” maybe nine or ten times. [CDNT65 2:50-3:25] But after I wound up working at Cahiers du cinéma, I turned away from French film. Friends at the magazine, like Jacques Rivette, thought it absurd that I could recite all of “The Raven” ’s dialogue and had seen Carné’s “The Children of Paradise” [1945] fourteen times.

A little while ago, you mentioned two Renoir films that you had also seen a dozen or more times. Could you say something about Renoir’s impact on you?

I think Renoir is the only filmmaker who’s practically infallible, who has never made a mistake on film. And I think if he never made mistakes, it’s because he always found solutions based on simplicity—human solutions. He’s one film director who never pretended. He never tried to have a style, and if you know his work—which is very comprehensive, since he dealt with all sorts of subjects—when you get stuck, especially as a young filmmaker, you can think of how Renoir would have handled the situation, and you generally find a solution.

Roberto Rossellini, for example, is quite different. His strength was to completely ignore the mechanical and technical aspects of making a film. They just didn’t exist for him. When he made notes in his scripts, he said all kinds of extravagant things, such as “The English army enters Orléans.” So you think, “O.K., he’ll need lots of extras.” And then you see “Joan of Arc at the Stake” [1955], where there are only ten cardboard soldiers jammed onto a small set. When Rossellini achieves serenity or even casualness in a film, like the one he did about India, it’s phenomenal yet at the same time inexplicable.

Such a film’s minimalism, its humility before its subject, is in the end what makes it such a magnificent work. My favorite Rossellini film is “Germany Year Zero” [1947], probably because I have a weakness for movies that take childhood, or children, as their subject. Also because Rossellini was the first to depict children truthfully, almost documentary-style, on film. He shows them as serious and pensive—more so than the adults around them—not like picturesque little figures or animals. The child in Germany Year Zero is quite extraordinary in his restraint and simplicity. **This was the first time in the cinema that children were portrayed as the center of gravity, while the atmosphere around them is the one that’s frivolous.

Rossellini reinforced a trait already evident in Renoir: the desire to stay as close to life as possible in a fiction film. Rossellini even said that you shouldn’t write scripts—only swine write scripts—that the conflict in a film should simply emerge from the facts. A character from a given place at a given time is confronted by another character from a very different place: and voilá, there exists a natural conflict between them and you start from that. There’s no need to invent anything. I’m very influenced by men like Rossellini—and Renoir—who managed to free themselves of any complex about the cinema, for whom the character, story, or theme is more important than anything else.

What about the influence on you of American cinema?

You know, we owe so much, here in France, to American cinema, which Americans themselves don’t know very well. Especially early American cinema, which Americans hardly know at all and even scorn. As for influential Americans around the time of the French New Wave, I’m thinking of Sidney Lumet, Robert Mulligan, Frank Tashlin, and Arthur Penn. They represented a total renewal of American cinema, a little like some of the New Wave directors in France.

They were extremely alive, the first films of these men, like early, primitive American cinema, and at the same time they were quite intellectual. Their movies managed to unite the best of both qualities. At the time, Americans scorned these filmmakers because they didn’t know them very well and because they weren’t commercially successful. Success is everything in America, as you know far better than I.

Why was the French New Wave an artistic success?

**At the start of the New Wave, people opposed to the young filmmakers’ new films said, “All in all, what they’re doing is not very different from what was done before.” I don’t know if there was actually a plan behind the New Wave, but as far as I was concerned, it never occurred to me to revolutionize the cinema or to express myself differently from previous filmmakers. I always thought that the cinema was just fine, except for the fact that it lacked sincerity. I’d do the same thing others were doing, but better.

There’s a famous quote by André Malraux: “A masterpiece isn’t better rubbish.” Still, I thought that good films were just bad movies made better. In other words, I don’t see much difference between a film like Anatole Litvak’s “Goodbye Again” [1961] and my picture “The Soft Skin” [1964]. It’s the same thing, the same film, except that in “The Soft Skin” the actors suit the roles they play. We made things ring true, or at least we tried to.

But in the other picture, nothing rang true because it wasn’t the right film for Ingrid Bergman or Anthony Perkins or Yves Montand. So “Goodbye Again” was based on a lie right from the start. The idea isn’t to create some new and different cinema, but to make the existing one more true. That’s what I had in mind when I began making films. There isn’t a huge difference between Jean Delannoy’s “The Little Rebels” [1955] and “The 400 Blows” [1959], either. They’re the same, or in any event very close. I just wanted to make mine because I didn’t like the other one’s artificiality—that’s all.

All François Truffaut movies on Great Movies.

Views: 383