Pretty Woman interview. In the late 1980s, J.F. Lawton was a starving-artist screenwriter living on the seedy fringes of Hollywood Blvd. in America’s movie mecca. Lawton worked odd jobs in post-production and struggled to pay his rent. Sometimes he slept in his car. He’d written a small shelf-full of scripts, mostly wacky comedies and ninja movies, but only one — a comedy about a one-legged lesbian stand-up comic — had absorbed that ever-elusive industry “heat.” Madonna was even interested in it at one point, Lawton will tell you.

It was around the same time that Lawton befriended several of the streetwalkers who frequented the boulevard. They were his neighbors in the red-light district, and Lawton, a Riverside, Calif. native born to a novelist-turned-journalist father (Harry Lawton) and pianist mother, would talk to them at a donut shop where he’d head for a coffee fix. He heard how many of them had fled dying industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest to come to Los Angeles. He even once followed one to watch her buy crack-cocaine. Another young woman told him how a wealthy client took her to Las Vegas, where she was wined and dined for a week before returning to the hustle.

The story reminded Lawton of The Last Detail, Hal Ashby’s bawdy 1973 dramatic comedy starring Jack Nicholson as one of two Navy Lifers who show a court-martialed 18-year-old (Randy Quaid) a taste of the Good Life before he goes behind bars. At the same time, corporate raiders were a popular news item as they pillaged factories closing across the Rust Belt. “And it was kind of a hot topic in Hollywood,” Lawton says, noting the buzzy 1987 release of Oliver Stone’s Wall Street.

Prostitutes. Money-hungry suits. A lavish but short-lived Cinderella fantasy. It was through this stew of percolating observations and ideas that the premise for the future classic Pretty Woman was born. “I thought, what if you got these two people from these very different worlds together — you got the guy who’s destroying jobs and families, and then you have a young woman who’s been impacted by this indirectly, and put them together,” Lawton says.

The screenplay was initially called Three Thousand at the time — that’s spelled out, NOT 3000, as widely circulated across the infinite sprawl of the internet, much to Lawton’s chagrin — referencing the amount of money New York corporate hotshot Edward Lewis agrees to pay call girl Vivian Ward for her company over six days as he schmoozes his way around Beverly Hills. And has been well-documented in film lore ever since the release of the Julia Roberts-Richard Gere 1990 hit that turns 30 today, the original story was not a rom-com at all. It was a darker, edgier drama.

“The original was more of an art, independent, prestige film,” Lawton says. “It was meant to be a prestige art film — kind of sexy, kind of gritty.” Though fundamentally, “It was about economic imbalance,” the writer, who admits he leans toward Marxism, adds later. “It wasn’t about sex work as much as an attack on out-of-control capitalism.”

When Lawton sent out the script, “It exploded all over town,” he recalls. The writer soon found himself a hot commodity in Tinseltown, and brought the project to the Sundance Institute. “When you write ninja movies, you don’t get taken seriously. When you write art movies, you get taken seriously.”

Soon Three Thousand was in the works in its original form at a small production studio called Vestron, with the relatively still-unknown Roberts, who’s biggest credit at the time was the earnest 1988 comedy Mystic Pizza, attached to star. But the company went belly up. Not long after, over at Walt Disney Studios, then-president Jeffrey Katzenberg held a weekly development meeting where he was apprised of projects his executives had read. Several mentioned loving Three Thousand, but all with the caveat that it’d never work for Disney, not even its more adult-oriented Touchstone Pictures arm. Still, Katzenberg was intrigued. “I have a vision for it,” he said. Disney then outbid Universal for the script.

The “sanitation,” as its sometimes been called, or “reconceptualization,” of the film had begun. It was soon re-named Pretty Woman after the buoyant 1965 Ray Orbison ditty it featured. Well-established comedy director Garry Marshall, fresh off the “you’ll laugh, you’ll cry” success of Beaches (his pivot into drama), was hired to helm, signaling a clear tonal shift.

One of the central topics of discussion through the film’s development at Disney was the ending. In the original script, Vivian has fallen in love with Edward — or at least the world he inhabits, but the feelings are not mutual. He attempts to drop her back off on the streets, but she won’t get out of the car. A physical altercation ensues: She hits him, he drags her out of the car. He attempts to give her the money, but she won’t accept it. When he insists, placing $3,000 on the curb, she throws the money back in his face. He races off, leaving her where he found her. (While the climax is indeed bitterly harsh, Lawton did include a coda that found Vivian and her prostitute BFF Kit, played by Laura San Giacomo, on a bus en route to Disneyland. “Garry always had the suspicion that Disney bought the script because they didn’t want the hookers going to Disneyland,” Lawton cracks.)

“Almost everyone involved [in development] said, ‘Well, we can’t have [Edward and Vivian] go off together at the end, because that would be a cop-out,'” Lawton explains. “At some point I said to Garry, ‘He either has to break her heart or fall in love with her, because it’s about these two people. There’s not a third way, because there was some talk about her going to work at the [Beverly-Wilshire] hotel, talk about going to work with David [Alex Hyde White],” the grandson of the business tycoon (Ralph Bellamy) who employs Edward.

Lawton was reminded of the stories behind the making of the original stage version and movie adaptation of My Fair Lady, based on George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmallion, which Pretty Woman also has shades of (though the screenwriter says it was not a conscious riff). Shaw fought against the idea of Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins living happily ever after together, but to no avail. Any resistance from Lawton would prove equally as futile. “And so my first drafts for Garry started to put the first inklings of them ending up together,” he says. “And the more I thought about it, the more I thought, ‘Well, why does she have to be punished? She’s such a great, lovable character. When I was writing the [original] ending, I was crying. It was like, ‘Here’s a character I love, and I’m the god making sure that she’s punished. And for why?'”

Another major change was making Edward redeemable. In the original version — as evidenced by his coarse dealings with Vivian during the climax — he was not exactly Mr. Right. Instead of cheating on his girlfriend, he was now recovering from a breakup. He originally intended to hire Vivian from the moment she gets into his car; instead he becomes more passive.

In casting its leads, Disney initially wanted Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer, who had previously worked together in Brian DePalma’s 1983 kingpin shoot-‘em-up Scarface. “If they had gotten those two, it probably would have been a very different film,” says Lawton. “Not exactly the original script, but undoubtedly a different film.”

Pfeiffer never really bit, opening the door back up for Roberts, who screen tested for the part and immediately impressed Marshall. Pacino loved the script, and the Godfather star went as far as doing a reading opposite Roberts. “He said, ‘She’s great, she’s gonna explode, she’s gonna be a huge star, she’s perfect for it,'” Lawton recalls. It sounded like he was in. “And then he said, ‘No, no, I’m not gonna do it. It’s not for me.'” (Coincidentally, a year later Pacino and Pfeiffer would go on to costar in the sudsy romantic drama Frankie and Johnny, directed by… Garry Marshall.) Burt Reynolds and Tom Berenger also turned down the role of Edward.

Marshall and Roberts then conspired to put the screws on Gere, who, ironically, didn’t consider the metamorphosed material prestigious enough. “It’s not my kind of movie, it wasn’t what I was looking for,” the actor told Yahoo Entertainment in a 2017 Role Recall interview. At the time, Gere was hammering out more serious fare like An Officer and a Gentleman, Breathless, and The Cotton Club.

He was also less than enthused by Edward. “I remember I kept saying, ‘Just put a suit on a goat and put him out there.’ It’s about the suit more than anything else,” said Gere. Like Marshall, though — and Pacino, to an extent — he was ultimately won over by star-in-the-making Roberts.

According to Lawton, the chemistry between Roberts and Gere was so powerful, “there was no other way to end it.” Factor in the goofy sense of humor and ad-libbing comedic chops of Marshall — not to mention Roberts, who improv’d some of the film’s most memorable scenes adding her infectious chortle to key moments, and a fish-out-of-water romantic comedy was in full bloom.

After its release, Pretty Woman went on to gross $463 million worldwide (or true to the spirit of the original’s title, Four Hundred and Sixty Three Million!). It was the second highest grossing film of the year in the U.S., narrowly trailing the supernatural romantic fantasy, Ghost. Along with the success of 1989’s When Harry Met Sally, it rejuvenated the rom-com in Hollywood. It’s also commonly credited with popularizing the “hooker with a heart of gold” archetype that Vivian embodies, though Lawton is staunchly opposed to that characterization.

“This is not a ‘hooker with a heart of gold’ story,” Lawton insists, citing the character’s roots in Giuseppe Verdi’s opera La Traviata, “the Die Hard of hooker with a heart of gold stories, it inspired everything that came after it. The form is ‘rich prostitute, courtesan, successful, happy to be a prostitute. Happy to be doing sex work. Poor guy — or guy of modest means — then gets free sex from the rich prostitute. Because that’s the male fantasy, ‘Oh she’s beautiful, everybody wants her, but she really loves me… And then at the end, she sacrifices herself for him.

“This is the opposite. She’s poor, he’s rich and he sacrifices for her. He gives up the biggest deal of his life for her.”

Like any impactful film dripping of nostalgia, Pretty Woman continues to elicit the services of think piece writers everywhere — the majority praising its revolutionary feminist qualities, others lambasting its degradation of women. Lawton is unabashedly proud of its gender portrayals. “She and him are complete equals. She’s not a pushover. She’s very tough, she’s very smart. She’s more than his equal in every single way, except money. He will always be able to outbid her,” he explains.

Speaking of bidding, Pretty Woman’s creator harbors no resentment toward the studio movie system for drastically lightening his once gritty drama. “I needed a job, to be honest. I was glad to finally be paying the rent,” says Lawton, who went on to write genre films like Under Siege (1992), Blankman (1994), Chain Reaction (1996) and DOA: Dead or Alive (2006), and in 2018 premiered a stage musical version of Pretty Woman in Chicago. (The play’s West End production in London was recently shuttered because of the coronavirus pandemic.)

“I missed the prestige that might’ve come from an artier version,” Lawton says. “But it’s nice to put something so hopeful out there.”

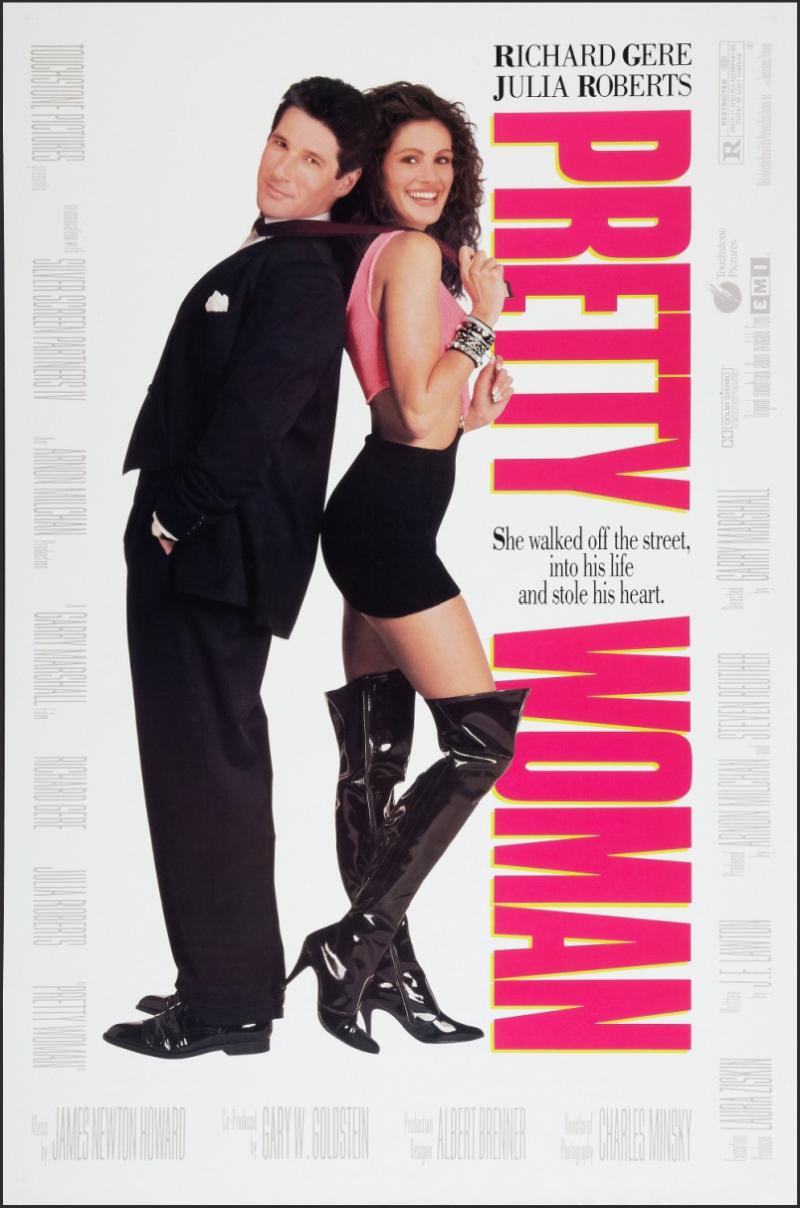

Pretty Woman (1990)

Directed by: Garry Marshall

Starring: Richard Gere, Julia Roberts, Jason Alexander, Ralph Bellamy, Laura San Giacomo, Amy Yasbeck, Hector Elizondo, Elinor Donahue, Judith Baldwin

Screenplay by: J. F. Lawton

Production Design by: Albert Brenner

Cinematography by: Charles Minsky

Film Editing by: Raja Gosnell, Priscilla Nedd-Friendly

Costume Design by: Marilyn Vance

Set Decoration by: Garrett Lewis

Art Direction by: David M. Haber

Music by: James Newton Howard

MPAA Rating: R for sexuality and some language.

Distributed by: Buena Vista Pictures

Release Date: March 23, 1990

Views: 238