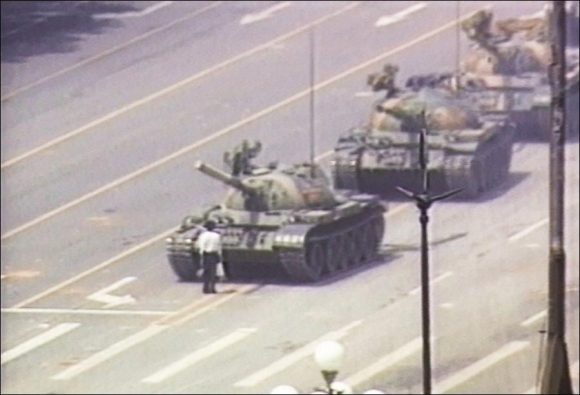

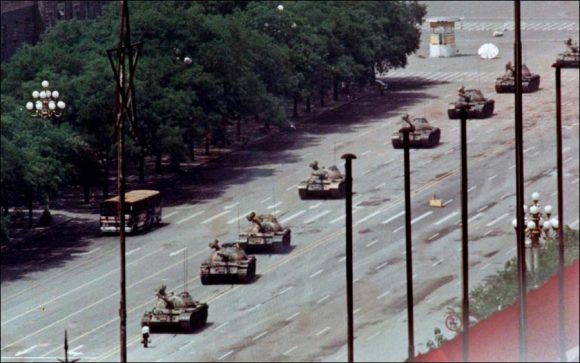

Nothing reflects the lasting potency of the iconic “Tank Man” photo quite like the dogged attempts to censor it on China’s internet. Practically any image that so much as gestures at the famed photograph of a man in front of a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square risks deletion from the country’s closely monitored web; recreations showing a line of books approaching a cigarette package, a swan before an oncoming truck and a grasshopper in front of a tire have all been removed.

According to Weiboscope — a social media monitoring project at Hong Kong University — even Francisco Goya’s “Third of May 1808” (1814), which echoes the Tank Man in sentiment and composition, could not make it past censors.

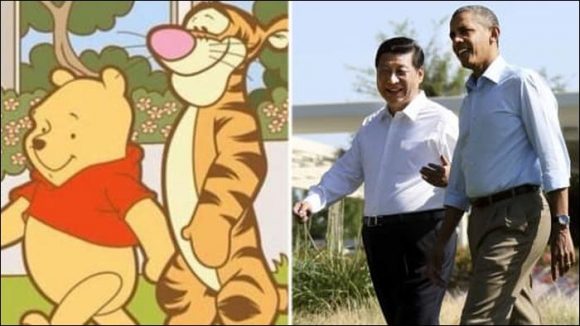

Behind China’s Great Firewall — which is more like a continually shifting, dynamic barrier — the Tiananmen Square massacre did not happen, the ongoing Hong Kong extradition bill protests are incited by Western countries and Winnie the Pooh doesn’t exist. This tightly controlled media climate has given rise to innovative circumvention tactics. While searchable keywords in plain text face automated deletion, digital images require more nuanced monitoring.

News articles from banned websites like the New York Times appear in upside-down screenshots on Weibo, a social site akin to Twitter (which is blocked in China). One writer managed to keep a photo from the Hong Kong protests up on WeChat, but only after adding brushstrokes and flipping it sideways. Resourceful netizens also use images of ordinary objects and cartoon characters as symbols in an ever-growing visual lexicon made for dodging censorship.

In recent months, the grip on the internet has tightened. In June, the protests and the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre kept censors on edge. The Washington Post and The Guardian were freshly banned, along with a handful of other major news sites. And a series of sensitive anniversaries in July — including deadly riots in Xinjiang in 2009 and the death of democracy advocate Liu Xiaobo in 2017 — pose more challenges for Chinese internet censors trying to clean the web of what government leaders call “spiritual pollution.”

Jason Ng, author of “Blocked on Weibo” (2013), notes that the Chinese government’s utmost priority is discouraging unified, anti-establishment action. But for Ng, the intrigue lies in the gray areas — where the state does more than prevent political unrest. “Clearly, it is not only protests that are being censored. There is some sort of intentionality,” he said. “It is fascinating to think through the moral reasons why things are removed. How does the government try to shape social mores? How do they try to shape culture through censorship?”

Some removed images are unsurprising: depictions of state-sanctioned violence, cartoons disparaging government leaders and aerial shots of protests. But many of them appear innocuous at first glance. All images — even harmless ones — of top Chinese political leaders are banned, except on official websites and approved blogs.

For other content, moderators tend to err on the side of caution since private companies, rather than the government, are responsible for complying with state guidelines. After President Xi Jinping eliminated term limits, for example, censors temporarily banned the letter “n,” which was likely a reference to the math symbol and was used to poke fun at the undefined length of his tenure.

The Chinese Communist Party is particularly sensitive to politically charged jokes. In 2013, when an image comparing then-US president Barack Obama and Xi Jinping to Tigger and Pooh Bear went viral, the rotund honey aficionado was quickly banned, and last year, the movie Christopher Robin did not release in China.

Charlie Smith, a pseudonym for the co-founder of GreatFire.org, a China-based information freedom organization, believes this is a testament to the sensitivity of China’s leader. “Quite honestly, if you were to be compared to any kind of cartoon character, you could do way worse than Winnie the Pooh — maybe Squidward,” he mused.

While Pooh Bear might be the best-known of the playful creatures removed from China’s web, he’s not the only one. Years earlier, censors blotted out mention of a 72-foot-tall inflatable frog after internet users likened it to former president Jiang Zemin, once nicknamed “toad.” And after a 2013 recreation of “Tank Man” replaced the tanks with inflatable rubber ducks, “the yellow rubber duck, in whatever context, was doomed to the blacklist forever,” Smith said.

Views: 152