Behind the sheltered mosques and madrasas of the Silk Road, a completely different chaos of chaos and chaos is full of Uzbekistan.

Under the pristine madrasah in Bukhara Lys blue-tiled Lyabi Hauz square, the pools were still standing. Men wearing long tunics were sitting in the roadside cafes, sipping tea from silver teapots. The narrow streets led to four-door towers surrounding the city center, where hawkers sold embroidered jackets, dried spices and leather shoes. Whatever I imagined about the ancient Silk Road cities of the steppe of Central Asia, they all came true.

Vladimir Kim rolled his eyes. Im I will show you the real Bukhara”

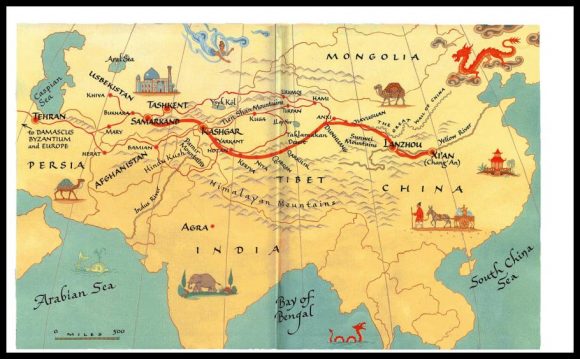

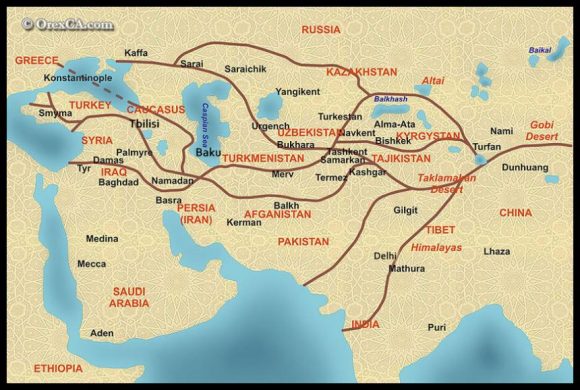

As far as I’ve learned, Uzbekistan has two sides. One side was meticulously restored (or aggressively, as some would say) cities, such as Bukhara and Samarkand, where 19th-century trade houses were turned into boutique hotels, and old stucco and marble shops became a breakfast room. This is Uzbekistan, where visitors are brought through tours and the city centers remain pale monuments at the time when this vast and barren region was one of the economic and intellectual centers of the medieval Islamic world. On the other hand, as the Uzbeks know, Uzbekistan is beyond the Silk Road.

When Kim, the only English-speaking guide in my Silk Road Tours group, realized that I was the only English-speaking traveler (the others spoke either French or Italian), she decided to cut off the planned itinerary.

Beyond the sheltered mosques and madrasahs of the Silk Road in Bukhara, he showed me another city with pale-colored and multi-storey Soviet buildings that remained from 67 years of Uzbekistan as part of the USSR. He also took a tour of a public market behind the castle, where old women sold their breads, each of which had their own Bukhara stamp (each province has its own line design), and young women came to buy soft wedding gowns like velvet.

I couldn’t hide my surprise when I found out that the price of one of these garments was 850,000 som (about 1000 TL som, which corresponds roughly to the average salary of an average worker). I thought the seller gave me a high price for being a tourist.

The people here put forth their intention for the wedding, Kim Kim said. People print invitations for the wedding or print them on paper by hand. They spend their savings on clothing and especially on food. As in many countries where nomadic societies have lived in history, hospitality to foreigners is regarded as the greatest virtue here, and it is a shame not to offer food to the guest who comes home in the villages.

While the rest of the group went to a restaurant near Lyabi Hauz, they sneaked in between silk scarves and imitation handbags and banged on the neck with the pumpkin-filled samsa desserts (the shape of samosa dessert in Central Asia) and popcorn bags on both ends. Who took me to the store.

I admired a coin scarf around a woman’s face, and with a broken Russian (the common language still spoken here) I asked where I could find one. He snapped his fingers and said something in Russian and Uzbek quickly, and as I understand it, he meant “come here…”

Two minutes later, we were standing in front of a counter made of corrugated tin, lined with arches in the shape of arches under the ceiling. I asked Kim if this lady worked here. “No,” he said, “he just wanted to help you, that’s all.”

In the historical center of Bukhara, in the tourist part of the city, commercial activities provide the basis for social interaction. But here, within a few minutes’ walk of medieval madrasas, I saw that dynamism turned into a joyful turmoil. The atmosphere of this market, freed from the daunting formality of tourism, was more evocative of a more dispersed, intertwined and surprisingly welcoming Russian basrobas than an eastern market.

At the heart of the market, an Uzbek family stopped me, carrying a large cardboard box with imitation Ray-Ban glasses, outside the restaurant, where the scents from boiled lamb piled us inside. They insisted that I buy a pair of glasses as a gift, telling me that I was the first American they met (of course they saw a lot of Americans on TV screens). Although I politely tried to reject it, I still did not succeed.

This dilemma in Uzbekistan continued to make me feel throughout my journey. In the morning, with the rest of the group, I visited not only Bukhara but also other Uzbek cities, such as ancient Samarkand, to explore the Silk Road.

Here, I would take photos of Registan, a charming square in the center of ancient Samarkand, where each large building was restored with modern blue mosaics, where it is impossible to tell where the past ends and where the present begins. I would visit the Uluğ Bey observatory, where one of the most famous scientists in the Islamic world was created with a 35-meter long sextant (angular distance meter) designed to measure the positions of stars instead of a telescope. I used to sit on the old rugs placed on top of each other in tea houses and eat honey baklava and drink cardamom coffee.

Then Kim would point us into another country.

On the suburban side of Samarkand, we used to eat a large plate of horse meat rice decorated with well-boiled eggs and quail filled with sausage. In the capital of the country, we exchanged money in the streets and liquor stores in Tashkent (the size of the black market for the Uzbek som was enormous). We went to Soviet-style bars and had a double on top of the drink, which was originally called vot okçay in by the Uzbeks and was translated as “white tea ancak, but actually meant vodka. We ordered lamb noodles and lettuce noodles covered with light pepper and enjoyed the night meal. We would buy spices like red sumac – bay leaf, wrapped in an old Russian newspaper and painted our fingers.

This was not the ideal Uzbekistan of President Islam Karimov, a controversial and authoritarian person who was described as “our first and last president”.

In this gloomy, yet cheerful Uzbekistan, we spent the last night of our tour at the Shodlik Palace Hotel in Tashkent, built in Soviet style. After looking at the dim sauna that resembles an abandoned warehouse rather than a spa, I asked them to bring a bottle of bek Uzbek Champagne ünden from the room service menu. However, the staff refused to do so.

I was told by the receptionist: in Go down instead, we’re pretty busy right now ”.

I met Kim and paid about 15,000 som for a double okchay in the hotel’s Hemingway bar (which, like most Hemingway bars, got its name from its proximity to alcohol rather than a real connection to the author), which seemed surprisingly expensive.

They put a bottle of vodka in front of us.

Kim That’s perfectly normal, Kim Kim said with a grin.

We raised our glasses in Russian and drank until we finished the whole bottle.

Views: 697