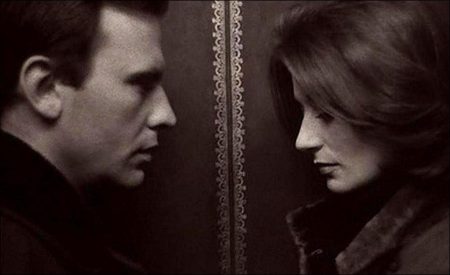

Paris-based race-car-driver and widower Jean-Louis Duroc and movie-script supervisor and widow Anne Gauthier meet when they drop off their respective adolescent children, Antoine and Françoise, at their Deauville boarding school after their regular weekend outings. Despite being attracted to each other, they are guarded with each other, speaking as if their former spouses were still alive.

Initially, they spend time together in their weekend outings with their children. As they get to know each other, as their attraction grows, and as their true marital status comes to light, they each make calculated moves to advance their relationship, however slowly and cautiously each still is in this venture. However, each must overcome some emotional baggage, especially concerning their late spouses.

Of course it’s pure pop—but done with deceptively simple, even casual technique, and the kind of light touch that comes from tremendous self-assurance. One is tempted to remark that its images seem to have been plucked from advertising, except that—such was the influence of the film—the advertising of the era may have been inspired by the film, rather than the other way around.

Making love, winning the audience

The real “killer” moment in this picture—which otherwise seems so insubstantial as to be hardly a movie at all, but a daydream of a movie—is the scene in which the man and the woman make love. At the time it was an extraordinary, even audacious moment in a movie. Here’s why.

In the midst of lovemaking, the man senses—from a nearly imperceptible change in the woman’s demeanor—that something is wrong. He stops: She is thinking of her late husband.

This was—and still is—one of the very few moments in cinema wherein a scene of lovemaking advances the story, rather than interrupting it. Most scenes of lovemaking are completely unnecessary, because the significance is merely the fact it occurs at all; not in the details of how it is accomplished.

Sex and the storyteller

It is not a solecism to show a sexual act in a movie, but it does present a serious, technical, narrative problem for movie makers: After a spectacle of sexual congress has completely distracted an audience, the story will have stopped dead in its tracks. How to get a movie started again, after that? That is a trick that requires finesse—and a storyteller’s cunning, of which writer-director Claude Lelouch and screenwriter Pierre Uytterhoeven had an abundance.

The trick is not in what immediately follows the scene but rather the rhythm which the screenplay had already established: A crisp, swift, intense rhythm—like a heartbeat—that prepares the audience to move forward from one scene to another like one wave succeeding another to the shore.

Detail and sensitivity

This part of the story shows a level of detail and sensitivity which rarely occurs in cinema inside or outside the bedroom.

Success and Influence

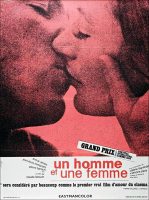

I don’t think American cinema was ever the same after this movie was shown. It was a hit in art-house theaters in the USA; it took two Academy Awards: Best Foreign Language Film, and Best Writing, Story, and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen; but what made it not only successful but vastly influential, was that the ABC Television network showed the movie in prime time, to an audience far larger than what it could have gained in theaters—embedding it, and its candid, casual use of intimacy—into popular taste.

And: There is that amazing, light, but elegant theme by composer Francis Lai! It makes American pop movie scores seem turgid and overbearing.

Un Homme et Une Femme (1966)

Directed by: Claude Lelouch

Starring: Anouk Aimée, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Pierre Barouh, Valérie Lagrange, Antoine Sire, Souad Amidou, Henri Chemin, Yane Barry, Paul Le Person, Simone Paris, Gérard Sire

Screenplay by: Pierre Uytterhoeven

Production Design by: Robert Luchaire

Cinematography by: Claude Lelouch

Film Editing by: Claude Barrois, Claude Lelouch

Costume Design by: Richard Marvil

Music by: Francis Lai

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Allied Artists Pictures

Release Date: July 12, 1966

Views: 800