It’s a story that’s told fast and easy. Vivian Morris goes to New York City after being kicked out of Vassar her freshman year of college. She moves into an old theater house owned by her offbeat aunt, Peg, and quickly adjusts to a booze-filled, action-packed life—albeit one behind the scenes.

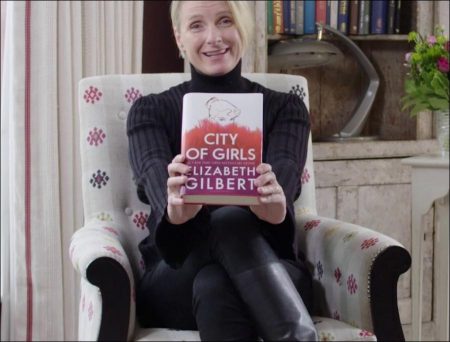

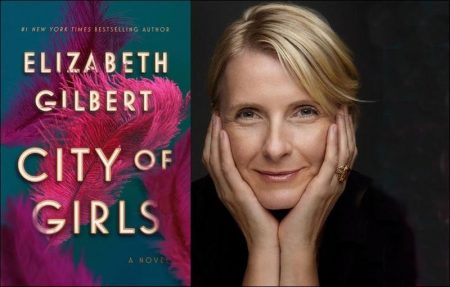

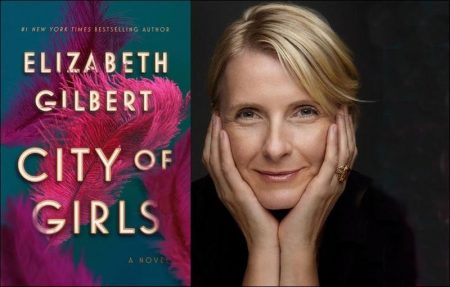

City of Girls is both the name of Elizabeth Gilbert’s ninth book and the title of the new musical created by Peg’s theater company. In an unconventional coming-of-age story, Vivian loves and loses, and learns that you can still make big mistakes and have a great life.

With City of Girls, Gilbert celebrates the jubilation of youth, the thrill of sexual exploration, the glamour of 1940s New York, and women who act on impulse and live to tell the tale.

Elizabeth Gilbert became a household name in the literary world more than a decade ago, after the publication of her memoir, Eat, Pray, Love. Her books take readers to unexplored times and places, and uncover experiences that we didn’t know we had in common. Her novel The Last American Man was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2002.

Elizabeth Gilbert Interview

She talked to April Umminger about writing City of Girls. Their conversation has been edited.

You’ve said that it took you six years to write City of Girls. Did you ever think about walking away and not finishing it, or was it something you knew you would always come back to?

Elizabeth Gilbert: Most of the time was done in research. And that’s about how much time it takes for me to gather enough material to be able to write in a different time period and feel like it sounds accurate and authentic.

I spent a lot of time doing interviews with old showgirls and dancers and actresses in their 90s and almost in their 100s—which was really fun. And then I did a ton of research on theater in the 1940s in New York City, and what it was like working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during the war, and that detail. And then in the middle of it, my partner grew ill and passed away.

I had a year and a half where I didn’t work on it at all, but then I came back to it as quickly as I could. Working on it brought me a lot of joy. It’s a book that I wrote for the delight of the story, and I’m hoping to offer it to people with the same effect. That’s my desire, anyway.

What was the inspiration behind the novel and placing the story in the theater, in New York City, in the 1940s?

New York City has been one of the love affairs of my life. I always call it the great mother. I’ve always felt it’s a very warm and welcoming place that’s taken me back any number of times when I’ve gone off in the world and failed at something. New York will always be like, “Ah, come back…we’ll let you come back. We’ll give you another seat at the table.”

I love the city, and I am particularly fascinated with New York in the 1940s. I feel like that was its most magical hour, and I wanted to write about that.

And then for years I wanted to write a book about promiscuous women whose lives are not beset by ruination because of their sexual desire. The typical classic Western canon novel about women who have sexual desires is that they always end up destroyed by it.

I’ve always felt like that was a little bit unfair. So I wanted to write a novel about girls who are young and reckless and wild. Certainly, consequences happen to them, but they don’t end up under the wheel of a train.

That’s one thing I liked about the book. You do not shelter these characters from negative consequences, but you don’t destroy them completely. How did you balance that?

Well, all I had to do is look at the mistakes that I made in my own life, mistakes my female friends made in their lives, mistakes borne of—especially in your youth—a combination of arrogance and ignorance.

We took our hits in the romantic and sexual field for being reckless, for being wild. But you know, we survived it. What I think is interesting is the subject of resilience. How do you come back from a shameful deceit?

All of us who are still living have done exactly that—if it’s not in the sexual realm, then in some other way in our lives. We made a bunch of errors and we thought it was the end of everything, and for a while it was… But you brush your knees off, and you keep going, and maybe your life is even richer for having had those experiences.

In researching this, did you find any books—or authors—that show a more evenhanded coming-of-age?

Mary McCarthy wrote a book called The Group that was about these girls who go to college together and go out into the world and what happens to them. She wrote pretty candidly about sex in a way that seems rare for the time.

Can you talk about the ending that Vivian has with Celia Rae and Edna? Did you consider changing the outcomes of those relationships?

Without giving too much away…I will say this: At the basis of every novel, whether it’s a period piece or a contemporary novel, novelists are always—in a way—writing about themselves.

There are mistakes we make in our lives that cannot be fixed. And despite our best efforts and our best intentions, there are people who sometimes will not forgive you. There are also things that we, in our own lives, cannot forgive in others. This is just part of the human experience.

I think part of maturity, part of one of those things that makes older women so fascinating and so wise, is their perspective on understanding not everything can be fixed. And then, who are you going to be? Who are you going to be despite not being offered that olive branch?

What that does in Vivian’s life is give her this well of compassion for people when they’re stuck in intractable situations because of their decisions. She has that humanity you can only earn when you have screwed up.

That’s very well put.

I’m sure nobody can relate to that. [Laughs]

Your books have touched so many people and inspired people to live their lives differently. Do you write primarily for you or do you start a book with your audience in mind?

I certainly got my start writing only for myself because no one was interested. If you’re not writing for yourself when you’re an unknown writer, then you’re not writing. It’s just you in your room doing your thing, so it’d better be coming for you or else it’s not going to be coming at all.

When Eat, Pray, Love happened, on my fourth book, all the sudden I was seen not only as an author but as a teacher. For the first couple of years, I had a very ambivalent relationship toward that. But I actually do try my very best to help people.

As an artist, the important thing is to do the work that lights me up, fires me up, that feels challenging and feels like it would be exciting. Then, as a human being, or a public figure, I think: What is my obligation to my reader?

Certainly, after Eat, Pray, Love there was no publisher in the world who was going to say, “You know, what we really want you to do is write a 500-page, 19th-century novel about botany.” That was like a marketing death knell, but for me, that’s what I wanted to do. So I did it.

That makes me wonder: How did the commercial success of Eat, Pray, Love affect your writing?

To be very candid, it’s given me financial independence in the world—which is glancingly rare for a writer and incredibly rare for a female writer. Part of the reason I wanted to write The Signature of All Things is I wanted to honor that incredible gift by writing the most ambitious and unlikely book I could possibly do that required the most amount of work.

Because I thought, I don’t need to pander to the market because I can support myself now, thank God. I can afford to take enormous, creative risk that other people might not be able to afford to do. I also felt like I wanted to do that in honor of all the countless generations of female artists who haven’t had the time or the resources to spend six years researching a novel. I felt like that was the best possible use—on the personal level—of that commercial success.

In terms of your writing style, how does it change from memoir to fiction? Do you prefer one? Is one easier than the other?

Novels are harder, but they’re so much more fun. I always have to go into a different world in order to write a novel. I wrote about lobster fishing off the Maine islands in the 1960s for my first novel, and then for The Signature of All Things I wrote about botany in the 19th century, and now I’m in the New York City theater world. It’s a lot of research. I like that part, but it’s an enormous amount of work.

The thrilling part about writing a novel is that you get to say what happens. I can control a novel in a way that I cannot control real life. It’s just so fun to make proclamations and you get to be the little God of that world. I just love the freedom of it.

In a memoir, you don’t actually get to say what happens. I’m so much more careful, because you’re often writing about other people’s lives. You have to be incredibly responsible about that and making sure that the facts are absolutely unassailable. It’s a little bit more restrictive in that way.

In reading about you and your writing process, I learned that you set your kitchen timer for 15 to 20 minutes—is that still the process? Do you journal? How do you begin?

This is something I really advise people who are writers, or who are new writers—I do believe the most valuable tool is the kitchen timer. Set it for half an hour if you’re beginning, or for an hour. The only rule is that you don’t leave. You don’t leave the chair, you don’t leave the desk. And you don’t look at your email, and you don’t look at Instagram, and you don’t do anything other than that for whatever the allotted amount of time a day. And when that timer goes off—you’re released!

You are obliged to not write again for the rest of the day because all you need to know is that you had a good day of writing because you filled that time. That’s how I begin every project. And what happens over time is you start to long for a little more time. That’s when you don’t need the timer anymore.

So what are some of your favorite novels, and what books are you reading now?

The book I read this year, that I love so much, is called Pretend I’m Dead by Jen Beagin. It’s about a woman who’s a house cleaner, who’s a big underachiever, and it takes place in New Mexico, and she’s trying to get her life together, and it’s cynical and funny and heartbreaking and just fantastically written. I’m buying it in bulk and giving it to all my friends.

Do you have a favorite novel that you’ve written?

You know, right now it’s City of Girls because it’s the newest and it’s fresh. It brought me so much joy to research it. Then, in the aftermath of my partner’s death, writing it returned me to joy from a place of very deep grief and loss.

There’s almost near-universal stress and anxiety in everybody right now, and I just feel like, “Take a break and read this book that goes down like a champagne cocktail, and maybe it’ll take your mind off your worries for a little while, as it did for me.”

The character of Vivian—in one way, she’s quite modern with her sexual endeavors, but in other ways she’s pretty passive in letting other characters direct her life.

The person I met in the real world who most inspired Vivian’s character was a dancer I met in her 90s, who lives in the same apartment on the Upper West Side that she bought in New York City in 1952. She came to New York from Chicago to be a showgirl.

At 95, and one of the most beautiful women I’ve ever seen, who was more than happy to sit and talk to me about her sex life. She had never gotten married and never had children…and she’d had a great time just being herself. It was fun for me to write a character who really did just kind of go along with the flow of her life, and yet by the end of her life, you can feel that she’s done it well.

Vivian says in the book, “Sometimes other people have better ideas for you than you have.” Vivian’s got a friend who’s a real go-getter, who is very ambitious, and she goes into business with her and it ends up being the best thing she could have ever done. But she would have never come up with those ideas—she’s just too much of a dreamer.

I think this book is a really fun read, but it is also very wise in some of the lessons that it comes to about life. It sneaks up a little on you. The tagline for your book is that “you don’t have to be a good girl to be a good person.” What do you want people to take from that?

The other thing that I wanted to do in this book was to write about women who are really on the hunt, in a very active way, for sexual experiences. As passive as Vivian is in other aspects of her life, she’s certainly not passive sexually. She goes out in the world and picks men up and has a lot of ambivalence about that when she’s younger. By the time she’s in her 40s, she has this clarity that this is just what she’s like—it’s how she is and it’s what satisfies her.

She ruminates on this idea that she’s not a good girl, certainly not for the time in which she was living, but she’s a good person. She has integrity, she’s honest, she’s loving, and she takes care of the people she cares about. That’s a big breakthrough for her.

“Good girl” is a very, very, very narrow category that is a kind of a prison in a way. But “good person” is broad. I’m glad the publisher pulled that quote and put it on the back cover. Even if people don’t read the book, there are some who might really feel better reading that line.

City of Girls really captures the evolution of relationships—that where you start is not where you end up, that important relationships can take you by surprise, that life is not so tidy. Was that a takeaway that you wanted?

Ultimately the takeaway is that it’s a celebration of female friendships. That becomes the constant in these women’s lives even though their personal lives and their romantic lives may be messy and chaotic; what remains and what endures are these deep, long female friendships. We all live our lives in chapters, whether we’re novelists or not.

The book has a lot of sex in it, and a lot of recklessness and wildness, but there is also a steadfastness of the heart between these women to each other. That is another thing I wanted to celebrate because I feel like that’s also a story not told enough. That’s the constancy in my life as well.

Any other things that you’d want your readers to know, that I haven’t asked, or that you hope your readers take away?

One of the main characters in the novel is Vivian’s aunt, Peg, who owns this shabby theater company in New York City. It puts on really lame song-and-dance performances for a local working-class audience.

What I love about Peg is she’s got a great perspective on herself. She doesn’t take her art very seriously. She knows that her job is to provide entertainment for people whose lives are difficult. She’s very adamant that they’re putting on cheap little love stories, with songs and dances and showgirls and magicians and maybe a dog.

And people will leave feeling better than when they came in. There’s a spirit of this novel that I want to feel like that. That’s the offering. This is an offering for your entertainment, and my hope is that you’ll leave the pages feeling a little better than when you came in.

Views: 185