Byzantine art and architecture, works of art and structures works produced in the city of Byzantium after Constantine made it the capital of the Roman Empire (A.D. 330) and the work done under Byzantine influence, as in Venice, Ravenna, Norman Sicily, as well as in Syria, Greece, Russia, and other Eastern countries.

For more than a thousand years, until the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, Byzantine art retained a remarkably conservative orientation; the major phases of its development emerge from a background marked by adherence to classical principles.

Artistic activity was temporarily disrupted by the Iconoclastic controversy (726–843), which resulted in the wholesale destruction of figurative works of art and the restriction of permissible content to ornamental forms or to symbols like the cross. The pillaging of Constantinople by the Frankish Crusaders in 1204 was perhaps a more serious blow; but it was followed by an impressive late flowering of Byzantine art under the Paleologus dynasty.

Byzantine Art

Mosaic

Byzantine achievements in mosaic decoration brought this art to an unprecedented level of monumentality and expressive power. Mosaics were applied to the domes, half-domes, and other available surfaces of Byzantine churches in an established hierarchical order. The center of the dome was reserved for the representation of the Pantocrator, or Jesus as the ruler of the universe, whereas other sacred personages occupied lower spaces in descending order of importance.

The entire church thus served as a tangible evocation of the celestial order; this conception was further enhanced by the stylized poses and gestures of the figures, their hieratic gaze, and the luminous shimmer of the gold backgrounds. Because of the destruction of many major monuments in Constantinople proper, large ensembles of mosaic decoration have survived chiefly outside the capital, in such places as Salonica, Nicaea, and Daphni in Greece and Ravenna in Italy.

Painting

An important aspect of Byzantine artistic activity was the painting of devotional panels, since the cult of icons played a leading part in both religious and secular life. Icon painting usually employed the encaustic technique. Little scope was afforded individuality; the effectiveness of the religious image as a vehicle of divine presence was held to depend on its fidelity to an established prototype. A large group of devotional images has been preserved in the monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai.

The development of Byzantine painting may also be seen in manuscript illumination. Among notable examples of Byzantine illumination are a lavishly illustrated 9th-century copy of the Homilies of Gregory Nazianzus and two works believed to date from a 10th-century revival of classicism, the Joshua Rotulus (or Roll) and the Paris Psalter.

Other Arts

Enamel, ivory, and metalwork objects of Byzantine workmanship were highly prized throughout the Middle Ages; many such works are found in the treasuries of Western churches. Most of these objects were reliquaries or devotional panels, although an important series of ivory caskets with pagan subjects has also been preserved. Byzantine silks, the manufacture of which was a state monopoly, were also eagerly sought and treasured as goods of utmost luxury.

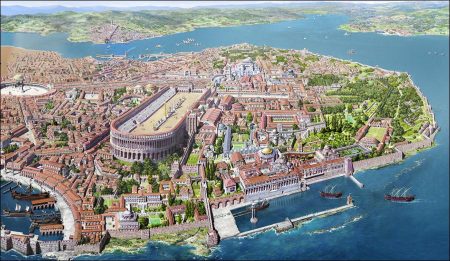

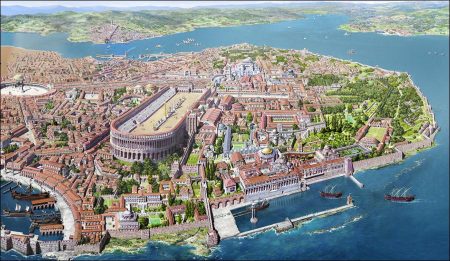

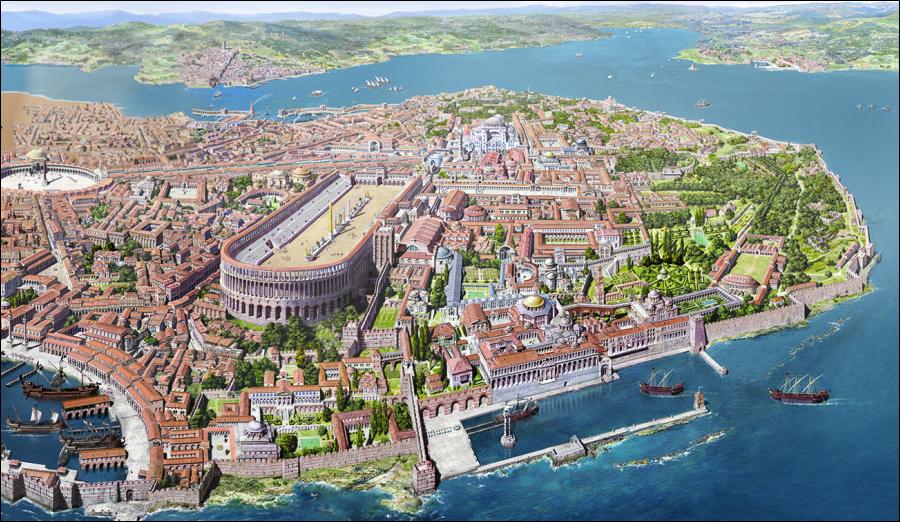

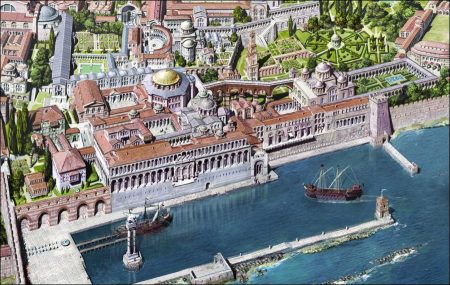

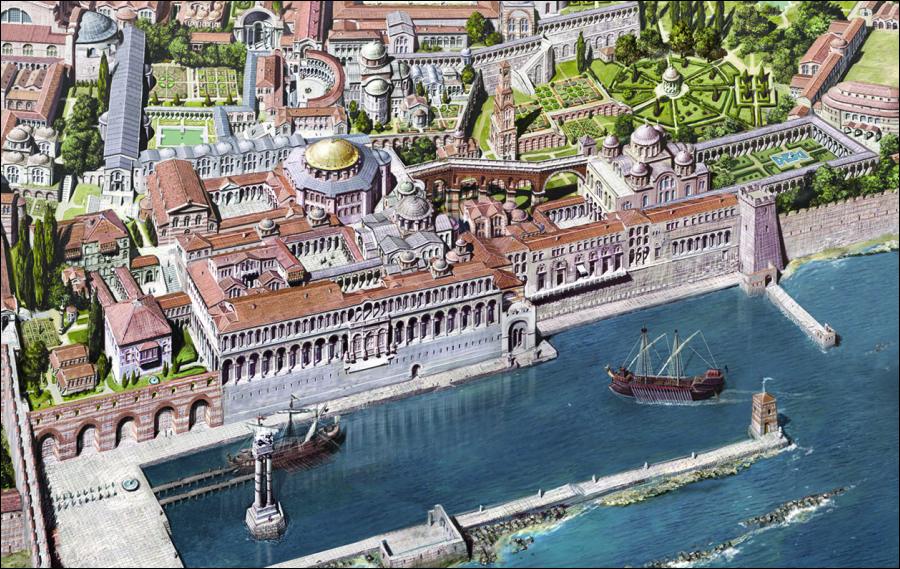

Byzantine Architecture

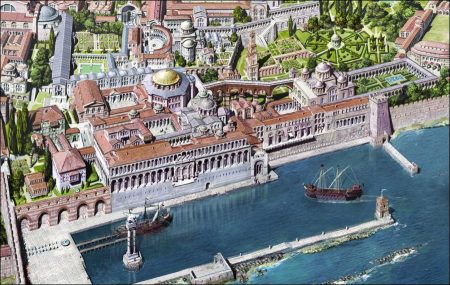

The architecture of the Byzantine Empire was based on the great legacy of Roman formal and technical achievements. Constantinople had been purposely founded as the Christian counterpart and successor to the leadership of the old pagan city of Rome. The new capital was in close contact with the Hellenized East, and the contribution of Eastern culture, though sometimes overstressed, was an important element in the development of its architectural style. The 5th-century basilica of St. John of the Studion, the oldest surviving church in Constantinople, is an early example of Byzantine reliance upon traditional Roman models.

The most imposing achievement of Byzantine architecture is the Church of Holy Wisdom or Hagia Sophia. It was constructed in a short span of five years (532–37) during the reign of Justinian. Hagia Sophia is without a clear antecedent in the architecture of late antiquity, yet it must be accounted as culminating several centuries of experimentation toward the realization of a unified space of monumental dimensions.

Throughout the history of Byzantine religious architecture, the centrally planned structure continued in favor. Such structures, which may show considerable variation in plan, have in common the predominance of a central domed space, flanked and partly sustained by smaller domes and half-domes spanning peripheral spaces.

Although many of the important buildings of Constantinople have been destroyed, impressive examples are still extant throughout the provinces and on the outer fringes of the empire, notably in Bulgaria, Russia, Armenia, and Sicily. A great Byzantine architectural achievement is the octagonal church of San Vitale (consecrated 547) in Ravenna. The church of St. Mark’s in Venice was based on a Byzantine prototype, and Byzantine workmen were employed by Arab rulers in the Holy Land and in Ottonian Germany during the 11th cent.

Secular architecture in the Byzantine Empire has left fewer traces. Foremost among these are the ruins of the 5th-century walls of the city of Constantinople, consisting of an outer and an inner wall, each originally studded with 96 towers. Some of these can still be seen.

Views: 829