Chanel’s collaboration with the Parisian artistic avant garde had been much more successful. As early as 1922 she worked with Jean Codeau, Picasso and the composer Arthur Honegger on a production of the classical Greek play Antigone; and from 1923 to 1927 she worked with Sergei Diaghilev and Codeau on ballet designs.

For the first of their joint works, Le Train Bleu, a fantasy about the Riviera, the dancers were costumed in bathing suits, pullovers and tennis or golf shoes, and the leading female role was a tennis player. So fashion, sport and the artistic avant-garde united to celebrate the modernity of modem life, and Chanel’s little black dress (American Vogue called it the “Ford of fashion”) became the epitome of modernist style.

The modernist movement in art transcended both national boundaries and those of artistic form, influencing all the arts from architecture to the novel. Visually, it was the embodiment of the ideal of speed, science and the machine. It was a love affair with a rationalist, utopian future, and in architecture and design this led to an ascetic functionalism that considered houses and flats as machines for living, fumiture and household artefacts as items for use, not ornament, and even human beings as machines.

More than almost any other aspect of mass culture, high fashion acted as a conduit for this esthetic, translating it into a popular language of pared-down design and understated chic. In architecture, the Bauhaus movement created buildings that used glass to reveal the inner workings of the design. They stripped away the superfluous ornament that had cluttered 19th-century architecture with what was now regarded as the sentimental idealization of a past recreated in pastiche.

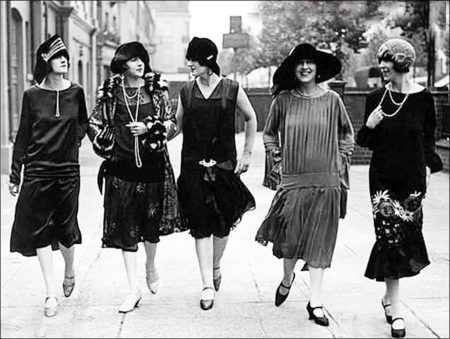

In dress, too, the watchword was now functionalism; clothing was simply an envelope for the body, which it impeded as little as possible. If there was to be adornment of any kind, it was to be of the art deco variety. Art deco was so called after the Exhibition des Arts Decoratifs, held in Paris in 1925. This exhibition had in a sense inaugurated the idea of a lifestyle, though the expression was not then used. It included a Pavilion of Elegance, in which the fashion designs of Chanel and Poiret, among others, were displayed. They complemented the furniture, ceramics and architecture – throughout, the few ornamental motifs and bright colors permitted were definite, clean-cut and jazzy.

In literature and painting, part of the modernism of modem art had been that the work of art interrogated its own intentions and questioned its own form. Perhaps what Cecil Beaton was to describe as the “nihilism” of the Chanel look was modernist too: it not only mocked the vulgarity of conspicuous consumption but, in inventing a look that was universal, international and reduced to the minimum, it almost sought to abolish fashion itself, creating instead a classic look that defied the one essential of fashion – change. At the same time the geometric, angular design of women’s clothing imitated the clean, spare lines of modern abstract art and design. Woman was no longer treated as a voluptuous animal; she had become a futurist machine.

Fashion thus disseminated the new esthetic of the modernist avant garde across two continents, and radically altered the way in which erotic beauty was conceived. Fashion became, superfiicially at least, classIess, and the great thing for a woman was no longer to look grand, but simply to look modem.

For the first time the New World and the Old engaged in a mutual cultural exchange of style and imagery. Although Paris stillled the way, the vamps and innocents of Hollywood – Theda Bara, Gloria Swanson, Mary Pickford, Louise Brooks constructed new tastes in beauty, while the “lost generation” of American expatriates settled in Paris and the south of France. Some of these hoped to create a new art and a literature that would reflect the often excessive and even tragic pleasure-seeking of the postwar generation.

Emest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald and many others tried to be as well as to describe a modern breed of sexually free beings, women and men whose minds, hearts and bodies were as untrammeled by traditional nations of morality as their bodies were by constricting clothes. Fitzgerald’s characters “discovered” the Riviera in summer until then it had been only a winter resort – and the suntan became another sign of working-class toil to migrate up the social scale. It became the status symbol of the globetrotter, who need never work and whose wealth permitted this inversion of established tastes. Society ladies took care to become brown as navvies, and Fitzgerald’ s heroine wore only pearls and a low-backed white bathing suit to set off her iodine-colored skin as she lay on the Mediterranean sands.

Related Link: View more Popular Culture stories

Views: 360