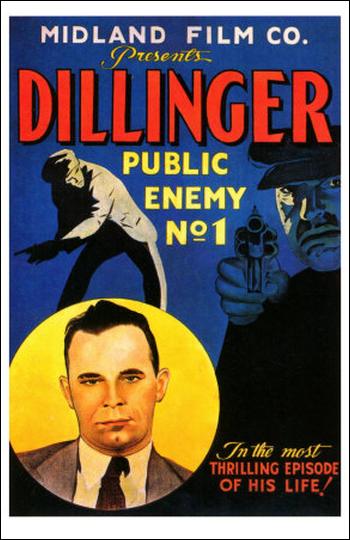

Though many essays, books, songs and films have told fascinating stories from the Great Depression, Michael Mann has long been interested in examining this turbulent era through the experience of a criminal who became a folk hero for a generation. For Americans in the early 1930s, who watched their life savings vanish and became jobless and hungry, they found a hero in a man who robbed and challenged the banks that caused the collapse and the government that could not fix it: John Herbert Dillinger.

Mann, who had previously written a screenplay about the era-about the famed train robber and bank robber Alvin Karpis-explains Dillinger’s appeal: “Dillinger, probably the best bank robber in American history, only lasted 13 months. He was paroled in May of 1933, and by July 22, 1934, he was dead. Dillinger didn’t `get out’ of prison; he exploded onto the landscape. And he was going to have everything and get it right now.”

“In assaulting the banks,” the director continues, “and outwitting the government…to people battered by the Depression, it’s as if he spoke for them. He was a celebrity outlaw, a populist hero.”

While no time frame in either Dillinger’s or nemesis Melvin Purvis’ lives could be considered particularly ordinary, the filmmakers were interested in a very specific window as they imagined Public Enemies. “It was this 14-month run of Dillinger’s life that opened a window for us into a confluence of forces that were at work during this period of American history,” says producer Kevin Misher. “There was a nexus between John Dillinger, perhaps one of the more famous Americans of the 20th century; Melvin Purvis, the underanalyzed G-man; and J. Edgar Hoover, a titan of American history. These three were in a dance of power and death.”

Soon after his release from prison until late June 1934, Dillinger embarked upon a whirlwind bank-robbing spree across the Midwest that attracted fervent nationwide attention, especially from J. Edgar Hoover and his nascent Bureau of Investigation.

To track and capture Dillinger, Hoover assigned a young, square-jawed agent named Melvin Purvis, whose profile actually inspired cartoonist Chester Gould in creating the look for Dick Tracy. But Dillinger and his men proved to be much wilier than the FBI agents, who would eventually bring down such gangsters as Pretty Boy Floyd (Channing Tatum of Fighting, the upcoming G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra), or their boss could ever imagine.

As they honed their techniques, Dillinger and his crew used a number of strengths to their advantage: a hardness hewn by years in prisons that were as lawless as they, the latest in automatic weaponry, a fragmented public safety system that had not yet been nationalized, state-of-the-art Ford V8 getaway cars and the knack for riding the wave of anti-banking sentiment from the very public whose banks they plundered.

While they could easily argue with his methods, few who saw the newsreels during Saturday matinees would disagree that someone was finally “sticking it” to the fat cats who they felt had destroyed their lives.

Time and again, the outlaw embarrassed government at every level and escaped from seemingly impossible situations, including a breakout of his crew from Indiana State Prison in September 1933, an escape from the Lake County Jail in Crown Point, Indiana, in March 1934 and an evasion of Purvis at the Little Bohemia travel lodge in northern Wisconsin in April 1934. And while his men never hesitated in the use of violence, the often chivalrous Dillinger could be counted upon to give money back to citizens during a bank robbery and not curse in front of female hostages.

When it comes to the law and lawless, Mann understands and appreciates that truth is stranger than fiction. Dillinger and his pursuers’ story was just the inspiration he was looking for in his next project. “Their mobility and use of technology made them almost invincible,” he says. “This was happening at a time when massive forces conspired against Dillinger: what Hoover built with the FBI-the first national police force, the first interstate crime bill, the use of very progressive, modern technology and data management. They were doing what is routine in law enforcement now, but what had never been done before in this country.”

Battling a doubtful Congress about the efficacy of his newly formed FBI, Hoover grew furious that Dillinger was becoming a folk hero to American citizens, while his schooled and polished agents were flubbing cases. Many of his colleagues saw the head of the bureau as an inexperienced, puffed-up suit and didn’t trust his methodology. In a frustrated effort to escalate the pursuit by Purvis and his agents, Hoover enlisted the aid of a Western lawman, Special Agent Charles Winstead, and two of his associates to track Dillinger. That, coupled with such orders to arrest relatives, girlfriends and associates of the criminals (in the FBI’s efforts to get tough on crime), did the trick.

While eluding the law, the bank robber had traveled across the country with girlfriend Billie Frechette, spending money in lavish quantities and rubbing elbows with the elite of Florida. Eventually, Dillinger’s luck ran out at the Biograph Theater in Chicago on July 22, 1934. As the screening of Manhattan Melodrama ended and he left the movie theater, law enforcement officials-under the direction of Agent Purvis and with the help of a Dillinger traitor called the “Lady in Red” (Chicago madam Anna Sage)-put him to rest with a slew of bullets. His legend only grew.

For grisly souvenirs of their hero, devastated fans of the “Jackrabbit” dipped handkerchiefs in the pool left by his blood, and thousands lined up at the morgue to view his body. From curious onlookers to lawmen, everyone wanted a piece of the legacy.

Dillinger’s primary antagonist, Melvin Purvis, received the lion’s share of the credit. And none were more unnerved by Purvis’ accolades in the celebration of Dillinger’s demise than J. Edgar Hoover. Continues Misher: “Dillinger was so famous that when he was killed, Purvis became `The Man Who Shot John Dillinger,’ even though he was not the man who pulled the trigger. As a result, Hoover started to resent the fame and acclaim that Melvin Purvis, G-man, had in the United States and drummed him out of the FBI.”

Three-quarters of a century later, Dillinger’s status as a legendary criminal is cemented. From the classic image of his crooked smirk as he draped his arm around one of his admiring captors, to his status as one of Chicago’s most famous residents, the dapper Dillinger remains iconic.

Views: 208