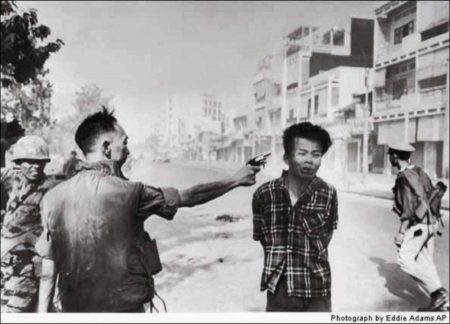

As the Vietnam War shook the country’s faith in their government, it also influenced writers, philosophers and theologians to question the metaphysical implications of these events. Vietnam, the first rock’n’ roll war, was also the first television war, with combat footage on the nightly news.

Johnson tried assiduously to manage television coverage of the war, pundits debated endlessly about whether television had “brought the war home” or had trivialized it as just another interruption in the stream of commercials, and whether the scenes of carnage and the reports of American atrocities had numbed its audience or had increased anti-war sentiment or street violence.

Television reporting was brutally attracted to scenes of violence and dissent – they made good pictures. By the end of the 1960s political groups denied conventional access to the media had recognized the staged act of violence as an effective means of gaining attention. Terrorism happened for the television camera. Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, saw the media as his enemy.

Although his1968 campaign was an object – lesson in the packaging of a candidate’s image, his attitude had been indelibly marked by his failure in the televised debates with Kennedy in 1960. Even before the Watergate Senate hearings topped the ratings in 1974, Nixon and his staff regularly denounced television’s “nattering nabobs of negativism.”

In common with most Western television systems, the Federal Communications Commissions Fairness Doctrine enforced the provision of equal time for the expression of opposing views on any given issue. Its effect was to secure the middle ground for television itself, and to make its presenters the arbiters of political dispute. Television’s credibility relied on its apparent neutrality, something that marked it out from the partisan allegiances of newspapers.

By the late 1960s television news was expected to be profitable as well as prestigious. CBS Evening News cost $7 million to produce in 1969, and made a profit of $13 million. The need for pictorial content meant that television took to “managing” the production of news in ways reminiscent of the “yellow press” at the beginning of the century. Needing to deliver stories with both drama and immediacy, journalists passed from gathering news to creating it, in the form of predictable and manageable events such as press conferences and publicity stunts.

American youth, on one hand, are brought up in the knowledge of American history, which includes many well-known and glorified examples of “rugged individualism,” and are encouraged to emulate this “truly American” trait. On the other hand, however, American youth are constantly challenged to conform to national and patriotic standards requiring high degrees of conformity to majority opinion.

Although these conflicting values have of course been a natural part of any era, they appear to have been unusually intense during the late 1960’s when dissent and counterdissent concerning the war in South Vietnam ran high. Some of the basic questions that emerged for the sociological observer concerned the surprisingly widespread public opinion which perceived dissent not as an expression of independent individual thinking and believing but as subversive and “un-American” conduct.

The music took shape amid the creative ferment and changing dynamics of the mid-60s, as popular music became more overtly political; opposition to the Vietnam War mounted; and the civil rights movement grew to encompass different minorities who began organizing and demanding changes to the status quo.

Television news stimulated an ever-growing cynicism and disaffection with politics by its emphasis on dissent and disagreement. At the same time the medium itself became the vehicle for the normal. It existed to sell viewers to advertisers, and advertisers were little interested in showing their wares to black ghetto-dwellers, for example, who might want the proffered consumer goods but lacked the wherewithal to purchase them. Television’s largest advertisers – the manufacturers of automobiles, cosmetics, food, drugs, household goods and, until 1971, tobacco – wanted the networks to supply them with a middle-class audience for their sales pitch.

In the late 1960s the American networks discovered that a detailed study of the audience provided them with a way of selling advertising time at higher prices by selecting programs aimed at a wealthier, educated audience. Fewer shows were aimed at middle-aged, middle-class viewers in large towns and rural areas. More programming was directed at a younger, urban audience with more money to spend. The controlled irreverence of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, launched in 1967, was one gesture toward this audience.

In October 1982, film audiences around the country cheered as they watched a Vietnam vet named John Rambo single-handedly take down a posse of blood-hungry policemen and National Guardsmen in the Oregon wilderness. A rousing populist fable that reflected the public’s growing discontent with the political establishment, Rambo: First Blood became a world-wide box office hit, spawning two sequels and transforming Sylvester Stallone, fresh off the success of Rocky, into one of the biggest stars of his generation.

Most notable, however, was John Rambo’s ascension to the ranks of global icon, a position which, two-and-a-half decades later, is undiminished. One can still find Rambo mudflaps and shopping bags in the Far East, Rambo T-shirts in Africa and Rambo action figures in Central America.

Related Link: View more Popular Culture stories

Visits: 138