On September 23, 1961, NBC introduced its new series, “Saturday Night at the Movies,” featuring Marilyn Monroe, Lauren Bacall and Betty Grable in “How to Marry a Millionaire.” This broadcast was an astounding success and pointed to Hollywood’s growing inclination to release its post-1948 movies to television. Seven more series representing all three networks and every night of the week appeared over the next five years.

The culmination of this trend was an ABC Sunday telecast of “The Bridge on the River Kwai” in September 1966.” It would be some time before anyone tried to make the same case for American television, which had changed little from the way Newton Minow, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, had described it to its producers in 1961, as “a vast wasteland”. Minow had just been appointed to his post by John F. Kennedy, and many in his audience might have expected gentler treatment from a president who had been elected, they believed, on the strenght of his appeal on television.

The precise birth date of the telefilm is arguable, although only a handful of contenders exist prior to 1961. Claims range from Ron Amateau’s 60-minute Western, “The Bushwackers, ” which appeared on CBS in 1951, to Disney’s “Davey Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier,” which was broadcast as three separate segments during the 1954-55 debut season of “The Wonderful World of Disney.”

Also, it was not uncommon during the late 1950s for TV’s dramatic anthologies to present some of their teleplays on either film or videotape. Three shows especially, “Desilu Playhouse,” “Kraft Theatre,” and “The Bob Hope Show,” filmed a number of their one-hour offerings, while a few of these presentations were even expanded into a second hour airing the following week as a finale of a two-parter. Still, these haphazard examples have really more to do with trivia than historical precedent, as the man primarily responsible for pioneering the formal properties of the telefeature is Jennings Lang, a New York lawyer who became programming chief for MCA’s Revue in the late 1950s.

Television obliged politicians to become performers in a way radio never had. Kennedy, youthful, authoritative and almost handsome enough to play the lead in a TV doctor series, seemed perfectly cast. Pursuing a policy of accessibility to the camera, he held live press conferences, delivered an ultimatum to Khrushchev via television during the Cuban missile crisis, and encouraged his wife to take the nation on a Tour of the White House. The impact of his assassination was intensified by the fact that he was not just the President, but a television celebrity whom the viewing public had been encouraged to feel they knew through the intimacy of the medium. For the four days between the assassination and the funeral all three networks suspended their regular schedules and carried no advertising.

By 1960 half the population of the United States depended on television as its prime source of news. Network prime time had settled into a mixture of half-hour comedy shows and hour-long action/drama series. Drama, like comedy, was constructed around a repeatable situation, usually provided by a professional activity. Lawyer- and doctor -shows provided an ideal format for hourlong stories featuring guest stars as clients or patients, but the same formula was used for series on teachers and social workers.

The formula had its limitations. The central characters had to remain unchanged by the episode’s events, in order to be in their proper places by the following week’s episode. The serial form provided the programming stability necessary to deliver viewers to advertisers on a regular basis. Networks tried to carry their audiences from one show to the next, employing the principle of Least Objectionable Programming. This meant that the majority of viewers who simply watched television, rather than selecting specific programs, would wacth whichever show they disliked least.

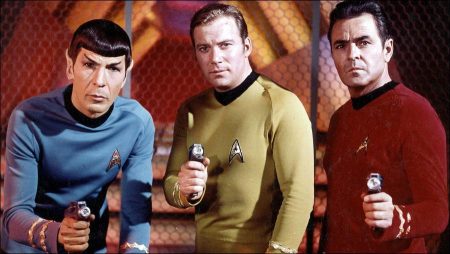

As mentioned earlier, the fall of 1966 was when ABC first decided to begin telecasting a number of Hollywood “blockbuster” films, including “The Bridgeon the River Kwai” on the River Kwai” and later “The Robe.” CBS, on the other hand, strove for prestige programming to counterbalance its lineup of popular, though pedestrian situation comedies, such as “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “Green Acres,” “Petticoat Junction,” the “Andy Griffith Show,” and “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.”

These specials were composed mostly of important American plays, like “Death of a Salesman” and “The Glass Menagerie,” which actually pulled moderate, though respectable ratings for a time. Most important, however, Lang was first able to interest NBC in financially promoting the made-for-TV form in the spring of 1964. By 1966, it was apparent to both Universal TV and NBC that they had gambled themselves into developing a television genre of enormous potential, as economic dividends were realized almost immediately from this feature-length hybrid. In contrast, however, much of the aesthetic and socio-cultural possibilities inherent in the telefilm would lie dormant for another five years.

The unit of television viewing was not the individual program but the daytime or evening schedule as a whole. As a result, television placed little emphasis on the distinction between fact and fiction. In sports and game shows it offered its audience an engagement with an endless dramatic experience, in which consequences and conclusions mattered less than the exuberance of competition, choice and performance. Television had a peculiar capacity to dissolve distinctions between comedy, drama, news and commercials.

Television’s other typical form, the talk show, perfected its formula in the early 1960s with The Tonight Show, hosted by Johnny Carson. Talk shows packaged personality as a commodity, but all television employed it; even newsreaders became celebrities.

NBC and MCA, Inc., inaugurated 1964 by creating “Project 120,” a never fully actualized weekly film anthology whose very name echoed the live dramatic series of the 1950s. NBC allotted $250,000 for the first telefeature, as MCAUniversal hired Hollywood journeyman Don Siegel to direct “‘Johnny North,’ an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s short story, ‘The Killers,’ starring John Cassavetes, Lee Marvin, Angie Dickinson, and Ronald Reagan in his last role. The movie that resulted eventually cost over $900,000 and was deemed by the network “too spicy, expensive, and violent for TV screens.”

Clearly, it was evident to both NBC and MCA from the outset that the budgetary constraints and the dictates of content would be different for the telefilm from what was previously expected for the usual theatrical picture. As a result, “Johnny North” was retitled “The Killers,” and the film was subsequently released to movie theaters nationwide. Mort Werner, NBC-TV vice president in charge of programming at the time, reflected upon this experience: “We’ve learned to control the budget. Two new ‘movies’ will get started soon, and the series probably will show up on television in 1965.”

View More Popular Culture Stories

Visits: 95