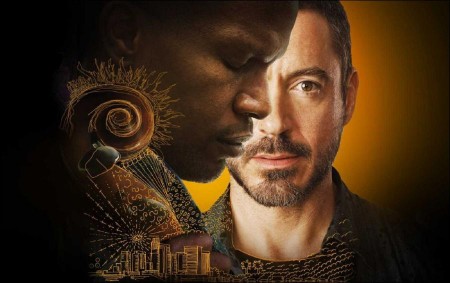

Prologue: “The Soloist” Journeys From Street to Screen

In April 2005, Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez kicked off a riveting series of features about Nathaniel Anthony Ayers, an astonishingly talented, yet utterly lost street musician Lopez had happened upon pushing his shopping cart and playing, with astonishing virtuosity, a two-stringed violin on the hard-knock streets of Skid Row. Very shortly thereafter, Lopez’s stories became a phenomenon unto themselves.

As Lopez began to dig into Ayers’ past as a Juilliard prodigy of great promise, and set out on his own challenging quest to bring dignity to Ayers’ current life on the street, the articles continued to draw a vast readership. Rife with emotion and eye-opening in their raw reality, the stories of Lopez’s unusual encounters with Ayers captured the city’s imagination. Ayers himself, with his whimsical belief that Beethoven must be the leader of Los Angeles, his unwavering commitment to art and personal freedom in spite of his circumstances, and his steely knowledge of how to survive the dangers of the streets – was an irresistible true-life character.

However, his story seemed to be about so much more than just a man down on his luck. It was about the secret, yet transcendent dreams that exist even at the American margins; it was about crossing the gulf between the privileged and the outcast; and, perhaps most intriguingly, it was about the often perilous task of trying to change a friend’s life, and how such a quest can lead paradoxically to exhilarating revelations about one’s own.

Recalls Lopez: “Readers got very involved in the story and began rooting in some way for Mr. Ayers.” Letters, e-mails and packages flooded into Lopez’s in-box, including violins and cellos, all to show their support for the homeless man whose meteoric ups and downs had become part of their daily lives.

It soon became clear that this story had leapt beyond the boundaries of Lopez’s column. He began writing a book about his remarkable, ongoing bond with Ayers, The Soloist: A Lost Dream, an Unlikely Friendship, and the Redemptive Power of Music, which was published in early 2008. Well before that happened, there had already been avid interest in transferring Lopez’s remarkable odyssey in befriending Ayers to the screen.

Although many producers expressed interest in the story, it was Russ Krasnoff and Gary Foster, partners in a leading production company Krasnoff/Foster Entertainment, who gained Lopez’s trust.

The producing partners had been driven by a near instantaneous reaction to Lopez’ columns. Explains Krasnoff: “I can’t remember ever reading newspaper articles that so moved me like those Steve wrote about Nathaniel. Here was a story about two men, one who is troubled and who society says is broken, and another who is seen as very successful. Yet Steve discovers in Nathaniel a passion he will never know. I was intrigued because Steve was not just investigating a story about an unusual homeless man; he was looking deeper into the motivations and rationales for all our lives. He had gotten down to the very root of these characters.”

Adds Foster: “We felt that in the right hands this could become a film about love, about inspiration, about the power of how people can help each other. That’s what we wanted. We saw right away that this was a story of life-altering friendship. Nathaniel helped Steve discover more of his humanity and Steve gave Nathaniel the hope for more in his life than just sitting in a tunnel and playing a two-stringed violin. There’s great drama, great emotion, and I was also inspired by the fact that it takes place in Los Angeles and explores the many aspects of the city, from the glimmering beauty of downtown to the stark grayness of skid row. One block separates them but it feels like they’re worlds apart.”

Soon after striking a deal with Lopez, Krasnoff and Foster brought DreamWorks on board, who in turn approached Oscar-nominated screenwriter Susannah Grant, best known for turning the true story of “Erin Brockovich” into an acclaimed and award-winning hit movie. To pique Grant’s interest, they simply sent her a packet of Lopez’s columns.

Grant quickly had in mind a vision for structuring Lopez’s prose into a dramatic screen narrative. She honed in on the different kinds of transformation each of the two men undergoes in their relationship, and the way friendship pushes each of them to places they had never imagined. “I always saw `The Soloist’ as a love story, a story of a great, deep friendship unlike any other, about two people trying to connect despite the loneliness of the city and the inherent differences between them,” she says. “There aren’t many movies about male friendship, so that was another plus.”

Ultimately, Grant fictionalized the two characters and situations to some extent. She created an ex-wife for Lopez (who is happily married) to add an extra layer of isolation to the columnist’s world; compressed Ayers’ two sisters into one character; and adjusted the chronology of their friendship in subtle ways to maintain dramatic pacing. At the same time, to capture the reality of the story, Grant spent considerable time with both Lopez and Ayers, getting to know them personally. She spent days hanging out at Disney Hall in downtown Los Angeles and going off on sheet music buying expeditions with the duo. “They’re two wonderful men and it was a privilege to spend time with them,” she says.

Later, on the set, Grant would be amazed to see Jamie Foxx and Robert Downey Jr. bring the very essence of each man to life through her words. “For me, it was almost unnerving how completely Jamie embodied the experience of being Nathaniel without ever being an imitation. The way he captured the vulnerability Nathaniel carries out into the world each day was amazing to watch,” she observes. “And I loved the assuredness Robert brought to the character. The way you see Steve’s heart open up bit by bit is really beautiful.”

Yet as inspirational as both Ayers and Lopez might be at times, Grant was also insistent on staying away from the urge towards fairy-tale sentimentality in the story. Rather, she wanted to reveal the truth of their challenges as people. “It was important to honor the fact that a significant friendship isn’t going to cure an illness like schizophrenia and that it is always going to be an ongoing struggle for Nathaniel,” she explains. “Most of all, I wanted to pay homage to the humanity of these characters.”

Adagio: Director Joe Wright Joins “The Soloist”

When it came to choosing a director for “The Soloist,” the filmmakers followed a suggestion from DreamWorks’ head Stacey Snider about a young, rapidly rising British director who had just garnered international acclaim with his debut film, “Pride & Prejudice,” and had recently completed an epic adaptation of Ian McEwan’s beloved novel Atonement. “Atonement” would go on to win a Golden Globe and a BAFTA Award for Best Picture of the Year, as well as an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture, and make Wright one of today’s most sought-after directors.

Gary Foster recalls, “When I saw `Atonement,’ I got very excited because I could see that Joe Wright was a man who believes in complex cinema, who knows that dialogue and characters matter. After we sent him the script, Joe called me and said, `I’ve read many scripts from CityHollywood and this is the first one that moved me to consider making my first film in placecountry-regionAmerica.’ He saw this story as a way of bringing Hollywood and British realism together, which we were very excited about.”

Although Wright had never made a film in the country-regionplaceU.S. before, he felt this was a film that might benefit from his distinctly outsider’s point of view. “Both Steve and Nathaniel are sort of outside observers of the world they live in, and therefore it felt more appropriate for me as an outsider to come in and tell this story,” he comments. “What interested me is that Steve and Nathaniel have kind of cut themselves off from society and also from their emotional lives. Steve is, in a way, as much of a `soloist’ as Nathaniel. And yet, they each learn something about love by trying to become friends.”

The chance to present a fresh cinematic view of Los Angeles also intrigued the director, who sees the film as setting up a mirror image to the glitzy city, which encompasses great beauty and streets of squalor all within blocks of each other. “I think this story gets to the tenacity of humanity that is expressed in Los Angeles daily life,” he says. “There’s an extraordinary survival instinct in L.A. that is both literal and in terms of the fantasies people have about coming here to fulfill dreams.’”

Before signing on, Wright flew to CityplaceLos Angeles to talk further about the script with the producers and used the opportunity to make his own personal forays alone into Skid Row. This had a profound effect on him and changed the direction of the film, firing up Wright with a desire to bring the rich humanity of this invisible part of the city’s population out into the open.

Recalls Russ Krasnoff: “Joe went on a bit of his own emotional journey in exploring Skid Row to determine if he could commit to immersing himself in this film. Then, he thrilled us all by saying, `I’m in, but on the condition that I be able to make the film in and with the community in which the story is being told.’”

Wright says it was his trip to visit Skid Row and the Lamp Community – the advocacy group that offers nearly 200 private apartments for the homeless, including the one where Ayers currently lives, that made everything clear. “The people I met on Skid Row are the reason I’m making this film,” he states. “They are the kindest, gentlest, funniest and most honest people I’ve ever met. If you let them, they will change your life. I hoped involving them would bring an authenticity to the film, but also would do something for them in return. It would be work, they’d learn skills and it would be something to be proud of. These people are the most disenfranchised people in American society and don’t generally have a voice. I wanted our film to be able to give them that voice.”

From the moment Wright committed to the movie, the filmmakers carved out time every day to reach out to the community. “Joe spent two or three days a week getting to know the people who populate Lamp Community,” says Foster.

Wright also utilized members of the Lamp Community, as well as others from Midnight Mission, Union Rescue Mission, the Downtown Women’s Center and Volunteers of America as extras. “It was an essential part of the process but it didn’t come easy,” notes Foster. “We had to be careful on so many levels, but at the end of the day, the members of the community who worked with us added a power and emotion to the movie that we couldn’t have imagined.”

Yet for all his emphasis on stark authenticity, Wright also wanted to shine a light on the joy inherent in Steve and Nathaniel’s odd-couple friendship. “I was always nervous about the film taking itself too seriously,” he says. “With material like this, which crosses themes of homelessness and poverty and schizophrenia, it would be easy to fall into that pitfall, so it was very important to make sure there was a lot of light and shade in the movie. The film goes to some places that are very dark, which meant that the light parts had to feel that much lighter.”

He concludes: “I wanted it to feel like we were taking a real look at this community, without glossing things over. There’s a lot of hope, light and beauty in this movie.”

Scherzo: Jamie Foxx and Robert Downey Jr. Take the Lead Roles

As distinctive and complicated a person as Nathaniel Ayers is, the filmmakers knew that the character would be an extremely demanding one to portray. After all, what actor would be able to travel the distance between Nathaniel’s undeniable genius and his unalterable moments of mental imbalance?

Fortunately, almost as soon as the script was completed, Academy Award winner Jamie Foxx expressed interest in the role. The actor was looking forward to using the same focus and commitment he had shown in his rich portrait of Ray Charles in “Ray,” and hit the ground running. Although he came to the production with the advantage of being a highly accomplished musician in his own right, he spent six intensive months learning advanced cello and violin techniques.

Notes Gary Foster: “From the outset, Jamie’s appetite for this role was voracious and he grabbed it to the point where he moved away from his life during filming. We rented him an apartment to play the cello and think about the next day’s scenes without interference from his normal existence. He really put himself inside this bubble and I cannot thank him enough for understanding what it was going to take.”

Adds Joe Wright: “Jamie has a heart the size of country-regionplaceAmerica and a very sensitive and gentle one at that. I believe he really loves Nathaniel, which was so important.”

Foxx immediately had an emotional reaction when he first read the script on a plane to CityplaceLondon. “I guess altitude makes you even more emotional and I was getting misty on the plane,” he says. “It’s so seldom you find a character captured with so many nuances and have everything work so well together on the page. I thought it was amazing. It’s a story about how trying to understand someone else’s world can take you a long way in your own, and it’s really a beautiful love story.”

Soon after taking on the role, Foxx met the real-life Nathaniel Ayers, which kicked everything into high gear. “It was just great to meet him, to get to know him up close and personal, to really be able to see his passion for music and his day-to-day life,” says the actor. “I wanted to get his speech down, I wanted to get all his subtleties down but, most of all, I wanted to capture his spirit.”

Foxx understood that accomplishing the latter was going to take him to some dark and uneasy places, as well as some magical ones. “It was tough,” he admits, “because I had to try to submerge myself into the mind of a schizophrenic in order to really understand what Nathaniel’s journey is all about. You have to kind of slip off the deep end a bit, and the biggest challenge was letting go.”

Still, no matter how strange Nathaniel’s reality could be at times, Foxx held on to a deep respect for his individuality and his sheer resourcefulness in navigating the twists and turns life throws at him. “The thing that makes Nathaniel like everyone else is that he is a person who is trying to make sense of the world. He has all these thoughts floating around, and he’s trying to make sense of them,” says Foxx. “From the outside looking in, it looks like he’s disturbed but actually I think he has figured out how to remain functional in his own way in our society. What seems abnormal to us is normal for Nathaniel. That’s his mojo, that’s how he gets around. And, even while he’s in this homeless situation, he’s toiling with these great dreams.”

The deeper he got into Nathaniel’s way of seeing the world, the more Foxx realized just how strange his first encounter with Steve Lopez must have been. “I think he thought maybe this guy was a dream or something,” observes Foxx. “And he certainly didn’t get why someone would want to write articles about him. They start off butting heads because Steve wants to save this guy’s life and Nathaniel doesn’t think his life needs saving. Yet, these two people who begin on opposite ends of the spectrum end up discovering each other’s worlds.”

The more Lopez allows Nathaniel to be himself, the deeper their friendship grows, culminating in a moment that brings Nathaniel face-to-face with his lost dreams of musical greatness at Disney Hall. “For Nathaniel, to see musicians in perfect harmony playing the most beautiful music is heaven and he is amazed that someone could give him such a special gift,” says Foxx.

Foxx himself found a special harmony in working side-by-side with Robert Downey Jr. to forge this life-changing friendship. “I was in awe working with Robert,” says Foxx. “I think he’s one of the greatest actors you’ll ever see; his talent is just so deep. On the set, I watched every little thing he did and took note of it.”

He continues: “The way Robert plays Steve Lopez, showing all his trials and tribulations, gives the film a breath of fresh air.”

For Foxx, the role was not only a chance to dive into a mind unlike any other, it was also an opportunity to tell a new story about the power of something very close to his own heart: music. Like Ayers, Foxx trained most of his young life to be a classical musician – a pianist – and knows first-hand the kind of single-minded dedication that is required to become a world-class artist. For the film, however, he had to train all over again, this time to transform himself into a virtuoso cellist in a matter of months. “For me, it was essential that Nathaniel’s playing be genuine,” says Foxx.

To take Foxx through a musical boot camp, the production recruited L.A. Philharmonic cellist Ben Hong, who had the distinct advantage of being a real-life friend of Ayers, and familiar with his musical style (indeed, later Hong would record the tracks Foxx plays on screen, as an homage to Ayers). Hong knew they would both have to work hard to get Foxx to the point of embodying a cellist of Ayers’ exceptional talent and skill.

The first order of business was getting Foxx comfortable with the large, body-shaped instrument. “Jamie is a great pianist, but the cello is obviously quite different from the piano. So one of the most important things was just getting the basic posture and hold of the instrument and the bow,” Hong explains. “From there, Jamie had to learn the fingerings and the bowings very accurately, because, since the instrument’s neck is right next to the actor’s face, the posture and hand positions are all very much on display.”

“Ben made it fun,” says Foxx, “but he also challenged and pushed me. We sat up for hours every night trying to make sure every aspect of the cello playing was seamless.”

To speed up the learning curve, Hong worked out a system where he would call out numbers to help Foxx remember which finger to play on which note. “The way we did it in our training was by singing the melody along with the fingering numbers to each note, and that worked quite well,” says Hong.

Foxx notes that the teaching process made an enormous difference. “It was a great system because it sort of translated the music directly to the fingers, and put me on a fast track to learning all the film’s pieces. It felt like I practiced a zillion hours a day, but when it came to shooting, it really came in handy.”

Although the cello is Nathaniel Ayers’ main instrument, when Steve Lopez first meets him he plays the violin – because a cello doesn’t fit in his shopping cart. To authentically create these scenes, Foxx worked closely with Alyssa Park, an internationally known violinist and the youngest prizewinner in the history of the Tchaikovsky International Competition. They practiced at least once a week for two months to learn proper violin bowing and fingering techniques.

As much as the reality of the film’s music was important to Foxx, he also wanted his performance to get across the metaphor of how we all strive to lead harmonious lives. “I think both Nathaniel and Steve can ultimately be seen as soloists,” says Foxx. “They’re each trying to find a way to play the music of their life – and have it be heard by someone.”

With Foxx already cast, the filmmakers began searching for an actor with the strengths to contrast and connect with him as Steve Lopez – which led them straight to Academy Award nominee Robert Downey Jr., fresh off his very different blockbuster role as “Iron Man.”

For Joe Wright, Downey’s casting was just as vital as that of Jamie Foxx. “When I started working on `The Soloist’ it seemed Nathaniel was the film’s extraordinary character, but I soon realized that Steve Lopez is equally so,” says Wright. “He is the film’s Everyman. Steve is someone who’s never been able to commit to other people and he goes into this relationship thinking that he can save Nathaniel, but actually it’s he who’s changed by the experience in the end. Robert was able to bring a great humanity and a fierce intellect to that.

For Downey, who portrayed a San Francisco Chronicle reporter in David Fincher’s “Zodiac,” playing a columnist in “The Soloist” was both familiar and a complete turnabout from his two most recent roles in big, summertime action films: “Iron Man” and “Tropic Thunder.” He says: “This last year I’ve done these really big, fun, showy movies and I think it was just what the cosmos ordered for me – to do something about humanity and humility and tolerance.”

It was Downey’s initial meeting with Joe Wright that sealed the deal. “I was so taken by the way he saw the movie,” he says. “He spoke about how he wanted to pepper the cast with actual members of the Lamp Community, how he really wanted this to be a film not about mental illness but about faith. He also said it was a love story, which I thought was a charming notion.”

Downey then met with Lopez, which gave him further insights into how to approach the role. “Steve is very charming, very engaging and a great storyteller but, when we met, he insisted that I not try to impersonate him in any way, so we ended up going in a somewhat different direction,” says Downey. “Joe and I talked about trying to really create a sense of a man in crisis, and that crisis is matched, mirrored and somewhat healed by this relationship with Nathaniel.”

After spending time watching Nathaniel and Steve together, Foxx and Downey also latched onto the fun at the center of their unusual relationship, something that really came across when they were on set together. “I think Robert brought levels of passion and compassion that really elevated the script,” says Krasnoff. “Any time an actor can take a brilliant script and elevate it, you have something very special. He brought humor and life to the movie in a wonderful way.”

Adds Foster: “I have never seen anyone on set as detailed as Robert. He works so hard. He looks for every moment and every beat of every scene and tries to find every opportunity to give you options. “It’s been an unbelievable pleasure and honor to watch him create.”

Fugue: The Supporting Cast

Surrounding Foxx and Downey in “The Soloist” is an ensemble of highly accomplished actors in crucial supporting roles. They include Catherine Keener, a two-time Supporting Actress Oscar nominee for “Capote” and “Being John Malkovich,” in the role of Mary Weston who, in the film, is Steve Lopez’s editor and ex-wife. (Utilizing some dramatic license, the character of Mary is actually a composite of several real-life figures in Lopez’s life. Lopez is happily married to his wife, Alison, who is not his editor at the Los Angeles Times.)

Keener had already expressed interest in working on Joe Wright’s next film without knowing what it might be but was thrilled when she found out it would be the story of Nathaniel Ayers. “I already knew of the story because I had followed it when Steve Lopez was writing about it, so it was already kind of etched in my being,” she explains. She also found herself intrigued by the fictional Mary’s role in Lopez’s life. “She’s the one who kind of calls him on his B.S.,” she laughs. “Their relationship is close, yet contentious. I think they were quite young and idealistic when they met and now, she’s the person who can challenge him to be who he used to believe he could be.”

On the set, Keener and Downey found a unique rapport that had traces of the classic Hepburn-Tracy repartee, filled at once with conflict and underlying affection. “Robert is so lovable, and so good at what he does, he makes it easy,” says Keener. “But when the character antagonized me, I reacted. We really had an excellent time together.”

Also joining the supporting cast was Stephen Root, last seen in the Oscar-winning “No Country for Old Men,” as Curt Reynolds, Lopez’s fellow reporter who becomes the victim of the newspaper world’s economic woes. “The character I play is kind of an amalgamation of a couple of Los Angeles Times reporters,” Root says. “He’s one of those guys that everyone in the office tolerates because he’s been around for a long time. But he’s not very confident that his job is secure, and he’s always looking over his shoulder. And, in this case, it turns out he’s right.”

LisaGay Hamilton, best known for her role on ABC’s “The Practice,” plays Jennifer Ayers-Moore, Nathaniel’s estranged sister, who isn’t even certain her brother is still alive until Lopez’s columns unexpectedly bring them back together. “I loved the honesty of the script and the very positive attempt to tell the story of someone who is quite brilliant but, unfortunately, suffers from the debilitating disease of schizophrenia,” Hamilton says. “That’s a topic that we don’t often see depicted truthfully in movies.”

Hamilton was able to spend some time with the real Jennifer Ayers-Moore, which added to her enthusiasm for the role. “The family couldn’t have been more supportive,” she says. “I saw up-close how losing touch with Nathaniel for so long was extremely difficult for Jennifer. I think their reunion was very important for both of them. Jennifer could finally face the feelings of responsibility she felt for her brother and Nathaniel regained the opportunity to have a vital family connection.”

Says Jamie Foxx of her performance: “LisaGay brought so much integrity to the part. I was captivated by her presence and at how much she is able both to take in and give out.”

Tom Hollander, who previously worked with Wright on “Pride & Prejudice,” portrays Los Angeles Philharmonic’s cellist Graham Claydon, a fictional character in the film, whose creation was inspired by several real-life musicians.“Graham is a cellist who works with Nathaniel and encourages him to give a recital that goes wrong,” Hollander explains. “He’s one of the people who tries to make Nathaniel better without any success. He’s also a very committed Christian, so he hopes that, through him, God can save Nathaniel and bring transformation into his life.”

Like Jamie Foxx, Hollander dove into cello training in preparation for the role. “Having to learn the cello was the most burdensome aspect of the job, but also the best,” Hollander says. “It was a wonderful experience for me.”

Rounding out the supporting cast are Jena Malone (who previously appeared as Lydia Bennet in Wright’s “Pride & Prejudice”) as a lab technician; comedic actress Rachael Harris as Lopez’s Los Angeles Times co-worker, Leslie; and Nelsan Ellis as David Carter, the head of Lamp Community.

Intermezzo: The Homeless Communiyet Extras

Director Joe Wright knew from the beginning he wanted to draw extras for “The Soloist” from the ranks of the downtown CityplaceLos Angeles community depicted in the film. For him, the extras were the heart of the film and its link to the real world.

To find hundreds of homeless background extras, extras casting coordinator Maryellen Aviano initiated a series of open calls at several homeless outreach centers, including Lamp Community, the Midnight Mission, Union Rescue Mission, Volunteers of America and SRO Housing – ultimately signing up 450 members. Among them were a core group of about 20, nicknamed “the Lamp Chorus,” who appear in several scenes with Foxx and Downey inside the Lamp Community building where Nathaniel Ayers resides. (The Lamp Chorus was also joined by ten SAG actors for scenes that required specialized performance skills.) Lamp and the other programs maintained their own personal advocates on the set to assure the extras’ needs would be effectively communicated.

Despite early uncertainty about how it might all work out, the experience was unforgettable for everyone involved. “I’ve never had a more enthusiastic group of extras in my 32 years in the business,” Aviano says. “The downtown community completely embraced the movie because Joe Wright spent several months working with them and invited them to share their experiences. The film gave them an opportunity to step up and show how resourceful they can be as a community.”

Wright worked with the homeless extras using an organic process and an almost documentary approach. To keep these diverse extras comfortable and relaxed in the strange world of moviemaking, Wright tried to maintain a very human atmosphere by keeping the crew’s footprint to a minimum so the set was spare with very little in the way of lighting or equipment.

Says Wright: “Working with members of the Skid Row community was, without exaggeration, kind of life-changing really. It taught me a lot of humility and to never underestimate anyone, and also that it’s possible, even within the film industry, to bring about some good and to have a positive, practical effect on people’s lives. That was tremendously exciting.”

The cast felt much the same way. Says Downey: “It was quite an immersion, being with these members of Lamp, many of whom were mentally ill, drug-addicted or in various states of homelessness. It was a fantastic leap of faith that this was somehow going to work out and we’d all interact and get along and simultaneously shoot a movie about this story – and yet we did.”

Adds Foxx: “Joe Wright had the beautiful insight to give the film the authentic quality of the people who live there. He took a risk and he made it work. Joe stuck to his guns and came out with his heart wide open and that opened us all up.”

Allegro Molto: “The Soloist”s Fresh Look At Los Angeles

Wright came to “The Soloist” with a very specific vision of the film’s design – aiming to reflect the naturalistic truth of life on the streets of CityplaceL.A. while at the same time bringing a musicality to the camera movements that mirror the transcendent themes of the story. For Foxx, the simple poetry of Wright’s approach was key to the film. “The way Joe uses the camera captures everything the movie is about,” says the actor. “He always contrasts the darkness with beauty and light.”

To do so, Wright brought on board a largely British team of collaborators, most of whom had worked with him before. He worked especially closely with Irish-born cinematographer Seamus McGarvey, who received an Oscar nomination for his lyrical photography for “Atonement.”

“Joe and I initially thought of a very simple, unadorned style for the film,” McGarvey reflects. “We both were thinking of the style of the British realists, particularly John Schlesinger’s `Midnight Cowboy,’ and the Italian neo-realists as well because I think this film, although grander than reality, does have some of the lyrical flashes the neo-realists had.”

He continues: “Most of all, we wanted a spare sort ascetic quality to the images, so you see the characters within a very believable frame. And because we used a lot of real people, we didn’t want to in any way enhance the artificiality that you sometimes sense in placeHollywood movies.”

Over several weeks, Wright and McGarvey storyboarded the entire film. They also made the key decision to shoot the film in 35mm anamorphic format, which, McGarvey notes, gives the film an even stronger sense of veracity. Just as important as veracity, however, was a musicality to the photography to echo the vital importance of music in holding together the threads of Nathaniel’s world. “Music was absolutely critical to the photography for this film,” McGarvey emphasizes. “We would often film to a playback of music. It’s amazing how this creates a synthesis between the actor and the camera, and how the camera sort of fuses with how the actor moves.

Music often inspired specific photographic sequences in “The Soloist.” McGarvey gives an example: “When Nathaniel is playing underground in the tunnel, we wanted to show how the music elevates him, and give a sense of him taking flight. We devised a shot that would lead us into a symphonic, lyrical sequence, a centerpiece scene in the film that required a 100-foot Strada crane to rise up above an aperture in the street overpass and reveal the city above.”

Wright and McGarvey also coordinated closely with Sarah Greenwood, the film’s production designer who won the BAFTA Award and received Oscar nominations for her work on “Pride & Prejudice” and “Atonement.” With “The Soloist,” she continues her collaboration with key set decorator Katie Spencer, a relationship that has spanned more than a decade.

The concept that Greenwood and Spencer had in mind was to contrast CityplaceLos Angeles’ soaring wealth and lofty-minded dreamers with its less visible pockets of struggle and grit. This was all done in a compact, if highly charged, two square miles, in that vastly diverse zone between Disney Hall, Skid Row and the Los Angeles Times building. “In downtown Los Angeles, within those two square miles, we could create a microcosm of all the different aspects of the city,” Greenwood says. “Here, you have images of the wealth of the city and the glorious Disney Hall and literally, within spitting distance, you have the extreme poverty of Skid Row. The film emphasizes this contrast between Steve and Nathaniel’s worlds by having Steve living on top of the hill from which he can look down at L.A. from on high, whereas Nathaniel is often found underground, in a basement or a tunnel.”

Greenwood spent time poring through the work of some of Los Angeles’ most notable documentary street photographers, citing the deep humanity of Alfredo Falvo’s 2007 photo book Lost Angels: A Photographic Impression of Skid Row Los Angeles and the baroque street photos of Philip-Lorca diCorcia as inspirations. Like those artists, she knew Wright wanted to capture the vibrant kinetic energy of this part of the city where sky and building and graffiti all flow into and through one another, creating a mix of human and natural rhythms.

Yet, shooting on Skid Row itself was not possible because the last thing the production wanted to do was to further disrupt already fragile lives. So Greenwood and her team of artisans took a bland section of industrial buildings between the Fourth Street and Sixth Street bridges and transformed them into a condensed Skid Row, circa 2005 (right before Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s Safer City Initiative, a controversial effort to clean up Skid Row of crime and drugs, went into effect). One by one, the design team replicated the graffiti-strewn buildings, rusted cars and homeless tenting that infamously lined the streets where Nathaniel lived and played. “All the merchants on the block were tremendously cooperative in letting us recreate Skid Row 2005, and it feels authentic,” says Greenwood.

The production design also extended to Nathaniel’s personal effects, which are emblazoned with the writings and scribblings he uses as another outlet for his constant urge for expression. To help create Nathaniel’s personal graffiti, Greenwood enlisted Sean Daly, a graphic artist who frequently works as a set designer for Vanity Fair photographer Annie Leibovitz, to be the “Hand of Nathaniel.” “The real Nathaniel writes on everything – himself, his clothes, the walls, his violin. There was an unselfconscious beauty created by him within his world,” says Greenwood. “Our artist, Sean Daly, became the `Hand of Nathanial’ and did a wonderful job recreating every aspect of this for us; he worked on all the costumes, sets, the cart, and the props connected with his character so they would create a cohesive link throughout the film.”

Daly went about his job in the same way an art historian might, analyzing every aspect of Nathaniel’s life and personal style. “The beautiful thing about Nathaniel is his ability to absorb the world around him and incorporate it into his clothing and everything he owns,” Daly comments. “He’s a literal genius who is not bogged down by the rules or the confines of details. His art permeates and inhabits his entire being.”

Continuing with the theme of authenticity, “The Soloist” became the first production ever to shoot inside the editorial offices of the Los Angeles Times building, filming in the third floor’s Metro section, the actual working space for Steve Lopez and his colleagues. “People had shot in the building before but never in a working newsroom,” notes producer Foster. “The then-publisher of the paper, David Hiller, just opened the doors and said, `Come in. This story is as much a part of us as anybody.’”

“The Soloist” also marks the first time a motion picture crew filmed inside the auditorium of Los Angeles’ newest architectural icon – the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall, which is practically a character in the film. Says Foster, “Deborah Borda, the L.A. Philharmonic’s CEO, Esa-Pekka Salonen and the entire staff of the L.A. Philharmonic welcomed Nathaniel back to music, and they generously allowed us to recreate that great moment.”

Says Borda of the decision: “It was quite unlike anything we have done, but then this orchestra is known for doing things nobody else does. It was a great fit, not to mention a unique opportunity. What a moving human story set against the backdrop of the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the remarkable place it occupies in the lives of Angelenos. And, of course, the story of Nathanial and the inspiration his relationship with the orchestra provides to himself and our musical family, is deeply touching.”

Other Los Angeles locations captured include Pershing Square Park on Olive Street, the site of the Beethoven statue Ayers believes signifies the composer’s standing as the city’s leader; the auditorium of Jordan High School in Long Beach, which stood in for New York’s Juilliard; Elysian Park, site of Steve Lopez’s bicycle accident; as well as the historic Millennium Biltmore Hotel, La Cita Bar and the Barclay Hotel, all in downtown Los Angeles.

The final days of shooting took place in Cleveland, StateOhio, where Ayers and his two real-life sisters grew up. For these scenes, the art department turned the clock back on a two-block stretch of the Hough section of the city, transforming it into a snow-covered family neighborhood circa 1966. They blanketed the area with snow, painted homes, and built an old-fashioned gas station, to create the backdrop for scenes in which the young Nathaniel ventures out to his Cleveland music school and watches the famous Hough riots that tore apart the community over a six-night span in summer 1966.

Equally key to bringing Nathaniel’s look to life was the work of costume designer Jacqueline Durran, who received Academy Award nominations for both of her previous collaborations with Wright on “Pride & Prejudice” and “Atonement.” As with the rest of the artistic team, the emphasis was on creating a street authenticity that would add to the realism of the story.

Sums up executive producer Patricia Whitcher: “We were very lucky to have Joe’s creative team because they’re an incredibly talented and dedicated group of people. From day one, it was always about doing right by Nathaniel and Steve’s story and giving the film a very subtle and authentic texture.”

Finale: “The Soloist”s Music”

One of the great, stirring mysteries of “The Soloist” is how two such disparate men as Steve Lopez and Nathaniel Ayers were able to create a life-changing friendship. The answer may lie in their ability to communicate at a level deeper than words: via the power of music.

Joe Wright realized from the start that this uplifting, inexplicable power had to be infused into the film, yet without ever overwhelming the basic humanity of the story. A creative decision was made early on to focus primarily on the works of Beethoven, one of many composers the real Ayers reveres and obsesses over, because Beethoven seemed to speak to the very core of Ayers’ love of music.

“Beethoven has such an enormous spectrum of emotions. Indeed, all human feeling is contained within his music,” says Wright. “And I think also that Beethoven is a fascinating character in terms of this particular story because he himself had so many personal struggles, including his deafness, to overcome.”

For the film’s original score, inspired largely by Beethoven’s soaring Third and Ninth Symphonies, Wright reunited with composer Dario Marianelli, who garnered an Oscar nomination for “Pride & Prejudice” and won both the Oscar and the Golden Globe for his memorable score for “Atonement.” “Dario is an enormous fan of Beethoven,” notes Wright, “and one of the great pleasures of this film was really learning, through working with Dario, about the history of classical music and especially Beethoven.”

Marianelli also had the further pleasure of having the L.A. Philharmonic at his disposal and the chance to utilize a true-life mentor to Nathaniel Ayers, Ben Hong, to record the cello tracks Jamie Foxx is seen playing.

Hong saw the chance to play cello as Ayers as an exciting challenge. “It was a very creative process because I had to basically act with the cello,” he explains. “I wasn’t playing as myself; I had to play like somebody else. In fact, I had to play like three different people. I had to play like the young Nathaniel, then as Nathaniel when he was at Juilliard, and then as Nathaniel in the present day. I altered the way I played the instrument for all of them to make it sound believable.”

Like Wright and Marianelli, Hong believes Beethoven will be another source of inspiration in the film. “There’s such a full spectrum of emotional expression in Beethoven’s works,” he says. “The music heard in the film moves from the tender and incredibly beautiful second movement of the Beethoven Triple Concerto to the very, very intense, almost angry and violent moods of certain moments of the Eroica Symphony, and reflects so much of the story.”

Continuing to use the local community, Wright brought in the University of Southern California Orchestra, conducted by Michael Nowak, to stand in for the Juilliard Orchestra in the performance of Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

The real coup was capturing globally acclaimed conductor and the Philharmonic’s then-music director, Esa Pekka Salonen, in his first film appearance, seen conducting movements from both Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) and his Symphony No. 9, from tracks pre-recorded for Marianelli several weeks earlier.

For Salonen, who became a part of Ayers’ and Lopez’s real-life story, it was a pleasure to be part of its retelling on screen. “Nathaniel is one of us because he’s a musician,” says Salonen. “His situation is very difficult and complex, but he’s still very much one of us.”

Salonen recalls his first, remarkable meeting with Ayers: “We spoke briefly about Beethoven and music and he said that he felt I was Beethoven reincarnated, which is quite a statement, so I would say it’s the best review I have ever had in my life.”

Most of all, Salonen was pleased to be part of “The Soloist” because of the moving nature of a story so close to all the things he holds dear: music, Los Angeles and the human spirit. “I think this story is a very concrete way we can see the power of music, the power of music to be an incredibly strong bond between people, the power of music to allow you to imagine things and to allow you to step out of your actual situation and, at least for a time, be completely free.”

About Los Angeles and U.S. Homeless

According to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, the most recent estimated number of homeless persons in L.A. County is 73, 702.

On any given night, the city of CityplaceLos Angeles is home to 40,144 homeless individuals.

Families make up 24% of the homeless population.

About 10,000 of the homeless in CityplaceLos Angeles are under the age of 18.

Over 50% of the homeless are African-American; nearly 24% are Latino and approximately 19% are Caucasian.

12% of CityLos Angeles’ homeless have served in the country-regionplaceU.S. military.

There are currently about 5,131 homeless individuals living in Downtown Los Angeles’ Skid Row. That number is down from the estimated 8,000 to 11,000 who were living there in 2005, when “The Soloist” takes place.

83% of the homeless in CityplaceLos Angeles are living outside of shelters, sleeping in streets, alleys, cars, encampments, doorways, etc.

Up to 77% of the homeless do not receive, or choose not to receive, the benefits available to them.

22% of the homeless surveyed by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority say they have been unable to get needed medical attention.

About 31% of homeless individuals say they are experiencing mental illness and 35% say they have a physical disability.

42% of the homeless say they have an addiction to drugs or alcohol.

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority notes that there is a shortage of 36,000 units of supportive housing for the County’s current homeless population.

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, there were about 170,000 homeless men and women in the state of StateplaceCalifornia as of its latest estimate in 2005 – before the present downturn in the housing market and the ensuing rash of home foreclosures.

The National Coalition for the Homeless estimates that in the placecountry-regionU.S. roughly 1 percent of the population is homeless (about 3.5 million), 39 percent of them children.

Production notes provided by DreamWorks Pictures.

The Soloist

Starring: Jamie Foxx, Robert Downey Jr., Catherine Keener, Tom Hollander, Lisa Gay Hamilton

Directed by: Joe Wright

Screenplay by: Susannah Grant

Release Date: April 24th, 2009

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for thematic elements, some drug use and language.

Studio: DreamWorks Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $31,720,158 (100.0%)

Foreign: —

Total: $31,720,158 (Worldwide)