About the Production

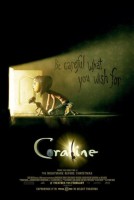

Combining the visionary imaginations of two premier fantasists, director Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas) and author Neil Gaiman (Sandman), Coraline is a wondrous and thrilling, fun and suspenseful adventure that honors and redefines two moviemaking traditions. It is a stop-motion animated feature – and, as the first one to be conceived and photographed in stereoscopic 3-D, unlike anything moviegoers have ever experienced before.

Coraline Jones (voiced by Dakota Fanning) is a girl of 11 who is feisty, curious, and adventurous beyond her years. She and her parents (Teri Hatcher, John Hodgman) have just relocated from Michigan to Oregon. Missing her friends and finding her parents to be distracted by their work, Coraline tries to find some excitement in her new environment. She is befriended – or, as she sees it, is annoyed – by a local boy close to her age, Wybie Lovat (Robert Bailey Jr.); and visits her older neighbors, eccentric British actresses Miss Spink and Forcible (Jennifer Saunders and Dawn French) as well as the arguably even more eccentric Russian Mr. Bobinsky (Ian McShane). After these encounters, Coraline seriously doubts that her new home can provide anything truly intriguing to her…

… but it does; she uncovers a secret door in the house. Walking through the door and then venturing through an eerie passageway, she discovers an alternate version of her life and existence. On the surface, this parallel reality is similar to her real life – only much better. The adults, including the solicitous Other Mother (also voiced by Teri Hatcher), seem much more welcoming to her. Coraline is more the center of attention there – even from the mysterious Cat (Keith David). She begins to think that this Other World might be where she belongs. But when her wondrously off-kilter, fantastical visit turns dangerous and Other Mother schemes to keep her there, Coraline musters all of her resourcefulness, determination, and bravery to get back home – and save her family.

The Genesis of Coraline

The story of Coraline Jones and her adventure in the Other World is one that has crossed many avenues of storytelling – father to daughter, pen to paper, book to movie, studio set to 3-D screen.

Once upon a time – in the early 1990s – author Neil Gaiman’s daughter Holly was, as he remembers, “four or five years old. She used to come home from school and she would see me sitting and writing. She would then clamber up on my knee and dictate little stories to me; these were often about small girls named Holly whose mothers would be kidnapped by evil witches who looked like their mothers.

“I thought, ‘Right, I’ll go and find a book like this for her.’ I looked, but there wasn’t anything even remotely like that. So I figured I would write that book, and I started to do so.”

Holly Gaiman reflects, “Coraline was a story that my Dad read me bits and pieces of when I was a little girl, a story that he had started writing for me and one which nobody else had ever heard or read. It’s a lovely story, one that has both haunted and inspired me since I was a little girl.”

But after completing a few chapters, Neil Gaiman found his career taking off, and it would be another five or six years before he found the time to return to Coraline. At which point he “suddenly thought, ‘Holly is getting too old for it.’”

However, she now had a younger sister, Maddy, and Neil Gaiman realized that that if he did not finish the book soon his other daughter would be too old for it as well. With a formal book contract being drawn up, he came up with a plan for productivity; “For the next two years, instead of reading in bed before I turned off the light, I would write Coraline.”

He began to keep a notebook beside his bed and before he went to sleep he would write 50 -100 words, maybe 5-6 lines each evening. “It was a very slow way of writing,” he admits. “That’s about 1 page every 6 days. But, doing it every night, eventually, I found myself approaching the end.” Finally, in 2000, he was able to spend a week finishing the book.

Central to the story is a childhood memory of the author’s; just as children are for a time certain that their toys come to life when they are asleep or not looking, the young Neil Gaiman had his own household suspicions. They were stoked by an old manor house that he was living in with his parents. He recounts, “There was a door in a living room that opened onto a brick wall. But I was convinced that it wouldn’t always do that. I tried sneaking up on it; I’d lean against it, as if I was doing something else, and then open it quickly and look.

“I thought if I could only approach it properly, there would be a corridor behind it. I had a dream that I opened the door and there was a tunnel. In the book, Coraline finds a door that has been bricked up, but one day she goes through the door and there is a corridor.”

Crawling along, she soon finds herself in the Other World and starts to settle in. She chooses to overlook the fact that Other Mother and Other Father have black buttons for eyes. “It is the kind of metaphor that allows for many interpretations,” says Neil Gaiman. “They are all correct; the eyes are the windows to the soul, the Romans put coins on the eyes of the dead, and so forth.”

It is the discovery of three ghost children, imprisoned long ago by Other Mother, that helps spur Coraline to forsake the Other World. She realizes that she is their only hope and that her own family back in the real world is also in danger. As the author notes, “I wanted to write a book about what being brave is; it’s being absolutely scared and doing what you must do, despite fear and obstacles.

“I also wanted to express that, sometimes the people who love you may not pay you all the attention you need; and, sometimes the people who do pay you attention may not love you in the healthiest way.”

The after-school story had become a bedtime one; having finished the book, Neil Gaiman read a chapter each night to Maddy Gaiman before she fell asleep. He admits, “If she had been scared or troubled by it, I probably would have put it away. But she loved it.”

Maddy Gaiman comments, “It’s a story that draws you in and keeps you there. You get attached to Coraline, and root for her to come out on top.”

The book, illustrated by Neil Gaiman’s frequent collaborator Dave McKean, was published in the U.S. by HarperCollins in 2002. This was “at the height of Harry Potter mania,” notes the author. “But it was also the first year that J.K. Rowling had missed her deadline, so we got media attention a children’s book would not normally get – and the book went straight onto The New York Times best-seller list!”

Authors Philip Pullman (the His Dark Materials trilogy) and “Lemony Snicket” (Daniel Handler) were among those who praised the book. Neil Gaiman reports that “because of its awards and because Coraline is written in a very plain vocabulary and has an interesting story, it got taught as a set text in schools.”

Its honors include the American Library Association’s Best Book for Young Adults; the Hugo and Nebula Awards; Child Magazine’s Best Book of the Year; and a Publishers Weekly Best Book citation, among many others. The unabridged audio book, read by the author, was voted a Publishers Weekly Best New Audio.

The book has inspired a short film by a trio of Italian moviemakers; a puppet show by an Irish theatrical troupe; a staging by a Swedish youth theater group; a hardcover graphic novel adaptation; and off-Broadway musical premiering in the spring of 2009.

Worldwide, the book has sold over one million copies. The author notes, “Of all my books, Coraline has been translated into the most languages – 30.”

Screen Vision

During the years of writing Coraline, Neil Gaiman followed with interest the feature film work of director and animator Henry Selick; the author had gone to see The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) the first week it was released, and then saw James and the Giant Peach (1996) as well. He remembers, “Henry was on my radar as a remarkable creative force. I would talk to my agent and he would say, ‘There’s this guy Henry Selick; you two would like each other.’ So when I finished the Coraline manuscript, I gave it to my agent and asked him to send it to Henry. This was about 18 months before the book was published.”

Selick reflects, “When I first read the manuscript, I was struck by the juxtaposition of worlds; the one we all live in, and the one where the grass is always greener. This is something that everyone can relate to. Like Stephen King, Neil sets fantasy in modern times, in our own lives. He splits open ordinary existence and finds magic.

“Coraline is very appealing to me, and I hope that she will be very appealing to children seeing the movie for a variety of reasons. She’s brave and imaginative and has got an overwhelming curiosity; if she sees something interesting, then she has to know about it. I loved that her ‘grass is always greener’ scenario turns out to be scary. When Coraline – an ordinary girl – faces real evil and triumphs, it really means something, as Neil has said.”

The director adds, “Neil invites the reader in to participate in Coraline’s adventure, and I wanted to do the same for the moviegoer.”

Gaiman says, “Within a week, Henry said he wanted to do it. Producer Bill Mechanic – with whom he had worked before – bought the movie rights, and Henry started work on the script immediately. By sheer force of never giving up, Henry has gotten the movie made.

Selick feels that “this was an ideal opportunity to take all I know about storytelling through animation, bringing those tools to bear on a story with a strong lead character.

“Neil was there with help and advice right from the start, yet was not overly precious with his book and would step away when I needed to focus. You want to honor the important parts of a book in adapting it, but you also have to invent and change as well.”

Once Selick decided that he would take the look of the movie into a different realm than Dave McKean’s artwork for the book, he brought revered Japanese illustrator and designer Tadahiro Uesugi on board as concept artist. Selick offers, “We’re going for both a classic storybook look and a strong graphic look, and Tadahiro is inspired by American illustrators of the late 1950s and early 1960s.”

Uesugi worked on the concept art in Japan for over a year, and then traveled to the U.S. to meet with Selick and illustrator Michel Breton. Uesugi would then remain in close contact with Breton from thousands of miles away; having established his brush-strokes and palette of colors with Breton during the U.S. trip, the two could continue collaborating on designs long-distance.

With a new draft of the script approved, Coraline entered pre-production in 2005. Art direction and storyboarding came first, as storyboard supervisor Chris Butler oversaw storyboard illustrators in visualizing every scene and character.

As crucial as this might be for live-action movies, for animated features it is doubly so. Butler explains, “It’s not like live-action, where you can use multiple cameras or do retakes. The animators are moving one frame at a time, so you need to know exactly what shot you’re getting before you actually do it. The benefit of the storyboards is that we work from the script to map out the entire movie in advance in picture form – often with some newly visualized ideas incorporated — and that material goes directly to the camera department.”

This phase of pre-production helps in getting what the director sees in his mind’s eye up on the screen. The process is adhered to through production, with the shooting schedule divided into sequences.

Moving storyboarding into the 21st century and beyond pen-and-pencils, Butler and his department worked with Wacom’s Cintiq LCD flat-screen monitors, which entail using an interactive pen directly on the screen. There are over 1,000 levels of pressure sensitivity on the pen-tip and eraser for precise image control, while the screens have adjustable stands for optimal working angles.

Butler enthuses, “With Cintiq, what we are able to do is build the entire movie out of our storyboard panels – complete with sound, music, and dialogue. We can watch it with Henry to make sure it’s [going to be] fine.”

But, how best to animate Coraline’s adventure? Stop-motion animation, the sole province of The Nightmare Before Christmas and the dominant one in James and the Giant Peach, was always in the forefront of Selick’s vision for Coraline. Despite his and Mechanic’s considering elements of CG (computer-generated) animation and/or live-action, Selick decided that “this story was perfect for stop-motion animation.”

“It is,” agrees Gaiman. “Stop-motion combines imagination with a tangible reality and solidity, and Henry’s work in the medium catches my heart.”

Stop Starts

“It’s puppetry without strings,” is how Coraline animator Amy Adamy describes the stop-motion art form.

Lead animator Travis Knight adds, “Every shot is a high-wire act.”

“You can do anything in stop-motion,” states storyboard artist Ean McNamara. “It’s like sculpting with light.”

Storyboard supervisor Chris Butler says, “You get to lose yourself in the fantastical. When you’re working on a stop-motion movie, you’re working on something special that you hope will be seen for decades to come.”

The stop-motion animation process was, is, and always will be distinctive, specialized — and uniquely enthralling to audiences. Single frame by single frame (and there are 24 frames per second in a motion picture), animators subtly and painstakingly manipulate tangible objects (characters, props, sets, etc.) on a working stage. Each frame is photographed for the motion picture camera. When the thousands of photographed frames are projected together sequentially, the characters and environment are animated in fluid and continuous movement. It is movie magic crafted by hand.

Coraline’s characters are brought to life through a unique art form. A stop-motion feature can be compared to a live-action feature in that there are physical sets that must be built and dressed; and players who need to be coiffed, clothed, properly lit – and directed.

But the entire world of the movie springs from the imagination, particularly from the creative minds of the animators, who move the cast members by a matter of millimeters for each individual frame. It is in that very movement where the one-of-a-kind nature of this moviemaking begins to emerge.

Henry Selick reflects, “The miracle of stop-motion, and one of the reasons it’s so magical for me, is what you see when you see a stop-motion animated character come to life; an actual performance through the puppet by the animator. They have to move forward, hitting their marks and saying the lines like any live actor would.”

The very first example of cinematic stop-motion is cited as the 1898 short The Humpty Dumpty Circus, in which British émigrés Albert E. Smith and James Stuart Blackton used the pioneering technique to bring a toy circus of animals and acrobats to life.

European animators were the first to use puppets and other objects to relate a coherent narrative, but it was California’s Willis Harold O’Brien who made it more of an art form over decades of refinement. O’Brien’s career spanned short films, the 1925 feature The Lost World, and (with sculptor Marcel Delgado) the original King Kong (1933). The ball-and-socket metal armatures created for the latter set a template that is still used today. O’Brien was honored with an Oscar for his work on Mighty Joe Young (1949).

One of O’Brien’s apprentices on the latter film was Ray Harryhausen, who would build upon his mentor’s techniques and whose “Dynamation” would inspire generations of animators, including Selick. Harryhausen masterfully combined live-action and stop-motion animation to get humans and creatures interacting in such fantastical films as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), and Jason and the Argonauts (1963).

Hungarian animator George Pal (György Pál Marczincsák) had arrived in Hollywood in the early 1940s, where he produced a series of “Puppetoon” short films for Paramount Pictures. Unlike O’Brien and Harryhausen’s techniques, Pal’s team used replacement animation, which required up to 9,000 individually hand-carved wooden puppets or parts, each slightly different, to be filmed frame-by-frame to convey the illusion of movement. This, too, is stop-motion animation, but from a different vantage point.

Several of Pal’s short films were nominated for Academy Awards, and Pal himself received an honorary Oscar in 1944. The director/producer continued to use puppet animation in such feature-length productions as The Great Rupert (1950), tom thumb (1958), and The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962).

Millions of adults and children from two generations are well-acquainted with the work of Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass. Using a stop-motion puppet process they dubbed “Animagic,” Rankin/Bass gifted television viewers with such classic holiday specials as Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964) and Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town (1970). Bass directed the team’s feature films The Daydreamer (1966) and Mad Monster Party? (1967), which utilized the same process.

In 1982, Disney conceptual artist Tim Burton made the short film Vincent with Disney animator Rick Heinrichs. Shot in expressionist black-and-white and narrated by Vincent Price, the picture was done in stop-motion.

A decade later, Burton hand-picked a team of artists and animators to create what would become the groundbreaking stop-motion musical The Nightmare Before Christmas, from his original story, tapping his onetime CalArts classmate and Disney colleague Selick to direct the feature-length film. The director remembers, “It was a very, very hard project, but we knew it was going to be a pretty cool movie. What we did with Nightmare was to take stop-motion into new arenas in terms of camera moves, lighting, mood and so forth.”

One more decade later, Selick would be doing the same with Coraline, while also joining the Oregon-based animation studio LAIKA , Inc. as supervising director for feature development.

Located in Portland, LAIKA has since 2003 counted Philip H. Knight, co-founder and CEO of Nike, Inc. as its Chairman of the Board. The company’s commercials division is named LAIKA/house.

Today, the 550-people strong animation studio specializes in the production of features, commercials, music videos, and other media, using a wide range of techniques; CG in addition to stop-motion, and (regular) 2-D in addition to 3-D. In fact, Selick’s first project at LAIKA was the 8-minute CG Moongirl (2005), which had its origins in a contest at the studio for a short film idea. CG modeller / compositor Michael Berger’s idea was picked, and Selick was chosen to direct. Exploring the other side of the Coraline process, Selick adapted the story as a children’s book for Candlewick Press, with illustrations by Peter Chan and Courtney Booker, two of the key artists who worked on the short.

The company also had a hand in the Oscar-nominated stop-motion feature Corpse Bride (2005), directed by Mike Johnson and Tim Burton, which was made in the U.K.

On Coraline, it was envisioned that the storied stop-motion process would be practiced as never before so that the story could be “seen through Henry’s world,” notes Neil Gaiman. “I was so glad when he called ‘Action!’ for the first time, and I knew it was going to be fun. He was the artist who, with vision and humor, would make something special – with cool stuff in it.”

With the Voice Talents of…

A character’s portrayal in animation involves several elements of performance. Voice work is one of them. Contrary to popular perception, on Coraline it was just the beginning for the character.

Henry Selick remarks, “We record the voices first and then we have someone read the sounds so we know where all the mouth positions should be. Later, the animators match the stop-motion puppets’ mouth movements to the words that the actors have already recorded.

“Sometimes it’s very challenging for the actors because they don’t have sets or props or costumes. They haven’t seen their characters in action, unless there is some existing test footage. So they are just doing pure voice work, and they have to record numerous different versions so that one can change one’s mind about what might be needed for a particular scene.”

The director clarifies, “The performance that the animator brings to the character is triggered by the vocal performance.”

Much as a director and producer would do on a live-action feature, Selick and Bill Mechanic began brainstorming casting ideas. It was imperative that Coraline, the girl who Selick admiringly says “cannot be held back,” be cast first. Dakota Fanning, who at the time was Coraline’s age yet already a veteran actress, got the offer for the role and accepted it.

She notes, “All kids, at some point, yearn for different things than they have. Coraline also has to learn to accept people for who they are and not wish them to be anything different, whether it’s her parents or Wybie or her new neighbors. You fear for Coraline and just want her to get home, having faith in her that she’s going to do so. She reminded me of Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz and Alice in Alice in Wonderland; in this story, there are scary parts, but it’s also very fun and a wonderful fantasy. Coraline is a great movie for both adults and children.

“Coraline is always looking for adventure, and she’s a collector of things that most people would not even pay attention to. But those are Coraline’s treasures.”

While Fanning was recording her dialogue for Coraline, her sessions were also digitally photographed, the actress explains; “They were videoing me, so if there was anything I happened to do – a gesture or a facial expression – they could put that into Coraline’s character.” In this regard, a voiceover portrayal can influence sculptors and animators’ work on the puppets.

Fanning continues, “When you’re doing a voice performance you don’t really have your body and your facial expressions to portray things, so in the studio you have to push the envelope with your voice to get your point across. You think, ‘Am I doing that right?’ Henry is very specific and very patient directing voiceover.

“What was helpful was, the first time that we recorded in the studio they brought in big pictures of some sets and all of the character models. Henry had given me pictures of what the house was going to look like.”

Fanning had a handle on her character from early on. She reveals, “The trick with the voice was to be frightened and smart at the same time. Coraline’s so scared, but she realizes she has to pull together and not let her fear overcome her. Since she’s the only person without buttons for eyes in the Other World, she realizes that the people there are no longer human and no longer have souls.

“So she knows that she has to come up with a plan to escape the Other World, and, with a little help from Wybie and the cat, she does get out of the situation, which is important to show children watching the movie.”

Neil Gaiman marvels, “Dakota conveys the character’s vim and spunk, and adopted this little midwestern accent, which she doesn’t usually have. You listen to her and think, ‘That’s Coraline,’ and not ‘That’s Dakota Fanning.’”

“She is a gifted performer who brings great skill and emotional depth to Coraline,” states Selick. “She understands the character and makes her believable.”

Fanning confides, “Coraline is more tomboyish than I am; I’m a little more girly than she is. But the clothes that she wears, I would wear in a second!”

The key relationship in the movie is between Coraline and her mother – or, perhaps more accurately, among Coraline and her mothers; her actual Mother and her Other Mother.

Selick elaborates, “Her real mom, Mel, is a talented writer and leader of the family. As the story begins, her Mother has whiplash and is on deadline, so she’s not great at pretending to care about every little thing that Coraline wants or needs in this new life of hers. Still, Mel knows what’s important; keeping the family together and keeping it going, which a real mom is great at.

“Coraline’s mom doesn’t have a lot of time for her right now, and Coraline discovers her Other Mother. This is a woman who looks almost exactly like her real mom, but a little prettier. With her, Coraline is offered wonderful homemade meals, a magical garden, and – it would seem – a mom who will cater to her.”

The moviemakers cast a wide net for the actress who could vividly convey both mothers’ characters. Selick reveals, “We had confirmed Dakota as the central voice, so I cut and tested about 70 actresses’ voices against Dakota’s. Teri Hatcher went right to the top of our list. She has this warm, beautiful instrument of a voice.”

Hatcher was intrigued with the project straightaway. She notes, “As a mom, I know it’s hard to find quality entertaining movies for the family, and that’s what Coraline is.”

In her voiceover debut, the award-winning actress takes on the tricky dual role of Coraline’s weary mother and the cheerily accommodating Other Mother. Although, as Hatcher points out, “It’s actually three different voices, for three different versions of Coraline’s mother.

“In the real world, Coraline’s mom has just moved, it’s raining, it’s muddy – nothing’s going right for her and her family. So, during one of our first recording sessions, Henry wanted her to say ‘shut up’ to Coraline. That line was a big deal for me, because I have never said ‘shut up’ to my own daughter in her entire life! But I think a lot of moms will relate to her because she is a good person who loves her child.”

Hatcher adds, “The second voice is the Other Mother. She’s the most surreally perfect mom anybody would ever want, with the answer to any question. Coraline starts to think that this Other Mother is better than her ‘old’ mother.

“Finally, I play what I call the Evil Mother, which is the Other Mother in her true colors. When she starts to not get her way, she becomes quite monstrous. She is actually an evil force that has existed for many years, thriving on the souls of children. For her, I had to let my inhibitions go and scream into the microphone!”

Selick adds, “We also found that when Teri would pull back and quiet down, it became scarier still. She loved the challenges. As Coraline’s mom, she has to be tough so we understand why Coraline would pull away. As the Other Mother, she is so warm and inviting that you want to hang out with her.”

But for the final voice, Gaiman remarks, “She goes from incredibly sweet all the way through to how-scary-can-you-get!”

Hatcher credits her director as being “supportive. He will really take the time to communicate to you just the subtle line reading he’s looking for. Then he gives you the freedom to try something different. He might say, ‘That was great and I didn’t expect that.’ All the time, you can see the passion Henry has for this project.

“As the process evolved, I became more confident in being more humorous, or more sarcastic, or more evil. What was amazing to me, seeing footage cut together, was how the animators take your voice and pick up every little inflection and make the characters so real. It’s artistic genius.”

Hatcher and Fanning were able to see the crew at work firsthand; although they recorded their voiceover performances separately with Selick in Los Angeles, each also paid visits to the LAIKA studios with members of their families to see firsthand the creativity going into the production process.

Fanning says, “I’m a big fan of Teri’s – Desperate Housewives is my favorite TV show – and I wish we had gotten to work together. I’ve met her once, and hopefully will again at the premiere of Coraline.”

Returning the compliment, Hatcher praises Fanning’s voice work – literally; “She’s wonderful; it’s amazing what she was able to do with the words, but also the breaths in-between them.”

While – as is the norm on animated features – the movie’s leads did not record their readings at the same places and times, two other actresses on Coraline did; Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders, a prominent U.K. comedic writing and acting team for three decades, recorded together as Miss Forcible and Miss Spink, respectively.

Selick muses, “These characters are Coraline’s new downstairs neighbors, but they really live in a fantasy world of their past, thinking they were great actresses when probably they were music-hall queens. They’re friendly to Coraline, although Miss Forcible is always very dramatic.”

When the moviemakers began discussing casting possibilities for the duo, Gaiman made his “one big casting suggestion, of French and Saunders. Dawn had read the English audio book of Coraline and done such an amazing job of it.”

Selick was receptive to the idea because “These two have been one of the outstanding comedy duos in the world for a number of years. It was important to have character actors, because these roles are not the usual ‘comic relief’ ones you find in most animated movies.”

The director went to London to record the pair’s voiceovers. He remembers, “We spent a whole day with Dawn playing Miss Spink and Jennifer playing Miss Forcible. At the end of the day it was good, but it wasn’t great. So I reversed their roles. There are a lot of actors who would have just walked out, but Dawn and Jennifer took a breath, nodded their heads, and said they would try it. They switched parts, and from then on everything was great.”

French adds, “Yes, we are quite often flip sides of the same person…I think a lot of working up character for voices is about trust; trusting the director, trusting the writer, trusting the other actor and being open to suggestions and trying something different.”

Saunders says, “It was lovely working with Henry. He gives you a lot of confidence. You always think it will be a bit pedantic to go over and over a line, but in fact you discover a lot more about the character. Normally, if Dawn and I are working on something together, we tend to go for what fits our natural rhythms. On Coraline, we tried other rhythms and other volume levels.

“Miss Spink and Miss Forcible have a kind of habitual bickering that happens often with older people. One person says one thing, and the other has to disagree. It’s a bit What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?”

French concurs, saying, “They try to top each other, even in their song; getting up an octave to prove that one is better than the other.

“I think that both children and adults respond very well to eccentric characters like these two; there is a sequence that takes place with them in the theatre [in the Other World] that will be divine, fantastical.”

For Coraline’s upstairs neighbor, the “casting call” was perhaps the most unique. In the movie, “Mr. Bobinsky is an eight-foot tall blue Russian giant,” explains Selick. “He keeps raw beets in his pockets, for healthy eating, and claims to have a Jumping Mouse Circus.”

Voicing this distinctive character is five-foot-nine non-blue-hued Briton Ian McShane. “I guess Henry probably saw and heard me on The West Wing,” laughs the actor by way of an explanation, referring to his appearance on the popular program as a Russian negotiator. “But I always enjoy doing accents, and voiceover; you’re one-on-one with the director and his vision, working together to create something.

“Henry’s movies are extraordinary; I’ve watched them with my grandchildren. They’re fabulously childlike and also spooky. The theme of Coraline is – things are always better at home!”

Selick enthuses, “Ian’s voice is like a bottomless well. He makes Mr. Bobinsky by turns imposing, comic, sad, aloof, and – in the Other World – a little villainous.”

Back in the Jones household(s), Coraline’s “put-upon father, Charlie, is voiced by John Hodgman,” notes Selick. “I had seen John on The Daily Show, promoting his book The Areas of My Expertise, and thought of him to play her father and Other Father. Listening to his voice with Dakota’s and Teri’s, he sounded perfect.”

Not long after, Gaiman did a reading in New York City where Hodgman was his interviewer. To his surprise, the author recounts, “John said, ‘Oh, by the way, I’m going to be in this movie…’

“Coraline’s dad is bemused and affectionate. He does that thing that fathers do when they embarrass their kids yet somehow think that they are being cool. But the kids just want them to go away. John has that down perfectly, and you both love him for it and wish he would stop…”

“With John’s great delivery and skill at improvising, he makes for a funny and sympathetic dad,” adds Selick. “While her mom is having a tougher time, her father cracks bad jokes and has a made-up song that he’s sung to Coraline her whole life. He sings with love, but his voice is terrible; he cooks with love, but his meals are terrible, too.

“In the Other World, the Other Father is a smooth guy; he’s what Coraline thinks she wants her real father to be like. The original direction for John was, ‘Just be Dean Martin.’ Now, I knew he could never be Dean Martin, but that it would still come off well. When he was doing his Dean Martin, it was more like Bing Crosby – but it worked.”

While in the Other World, Coraline also encounters a black cat that she has only recently met in the real world. The enigmatic and often feral animal has the ability to move between the two worlds – but only speaks in one. Selick reveals that the cat is “Coraline’s reluctant guardian angel because – unlike all the ‘Other’ characters – he doesn’t have buttons for eyes. It is in fact the same cat — and it can speak in the Other World. It can travel between worlds at will because there are cat ways in and out of most any place.”

As voiced by Emmy Award-winning actor Keith David, this sage feline really is “the cat’s meow,” laughs Fanning.

Coraline’s new acquaintance Wybie Lovat is a character added by Selick for the screen version. He explains, “Coraline has a lot of internal thoughts, and I needed somebody for her to share her thoughts with and create a little more conflict. Wybie is a local kid who is clever but lonely. He’s built himself an electric bicycle which he uses to explore the woods nearby.

“Wybie’s grandmother – another character added for the movie – owns the house that Coraline and her family have just moved into. Wybie has a few clues about the house’s secrets, but he doesn’t really know. When he finds out, he proves to be a true friend to Coraline.”

Selick selected Robert Bailey Jr. to voice Wybie. Like Dakota Fanning, Bailey Jr. is already a veteran actor by virtue of his having started a successful career at an early age; like Teri Hatcher, he makes his feature voiceover debut in Coraline.

Maddy Gaiman assesses the actor and his character as “a good addition to the story. He’s there for Coraline when it counts!”

Two Worlds, One Studio

No project is more unique and innovative in contemporary feature animation than Coraline; it is the biggest production ever to be made in stop-motion animation, and the first to be made in stereoscopic 3-D.

To make the movie at LAIKA, Henry Selick worked with “an incredible crew, many of whom I’ve known for more than 20 years.”

More than 20 people relocated to Portland from other parts of the country, and even from abroad. Lead animator Travis Knight comments, “LAIKA has roots in stop-motion, but we have a broad range of projects, and I guess the thing that ultimately unites them all is a singular, really creative voice. Every movie we make has to have someone behind it who has a powerful vision, like Henry does.

“But of course, moviemaking is a collaborative effort. Ours involve everybody at LAIKA, each bringing something of themselves to these captivating stories – while expanding people’s senses of what animation can be, with bold and innovative design.”

“After living with this project for more than seven years, I know it intimately,” notes Selick. “What was truly exciting was seeing it coming to life before me with what other people brought to the project. The LAIKA family came together to concentrate on this movie.”

Neil Gaiman comments, “I hope that people are and will be reading my work who were not even conceived when it was written. Similarly, at LAIKA, the people there are not interested in making movies that last just for the moment. They want to make ones that last forever. That is why there was no point at which I lost faith in Henry and the people at LAIKA.

“What I didn’t realize until I visited the sets out in Oregon was that absolutely everything you see on the screen had to be made after being designed or signed off on. Every blade of grass had to be painted or built out of fake fur.”

With elements in each frame of Coraline being created and posed by hand, it took an entire week of production to complete 74 seconds of movie footage.

Yet, clarifies Selick, “Any animated movie takes a long time to make. A stop-motion feature doesn’t really take longer than a computer-generated one.

“Having done tests with the sets, props, puppets, and camera, when we roll a shot it has a very high success rate. Unlike in live-action, where you start shooting and have to get coverage from different angles, we are only shooting the pieces that fit together perfectly.”

As with a live-action movie, the shooting of Coraline was divided into individual sequences that were usually grouped by the locations of the scenes.

“With miniature puppets, miniature props, and miniature sets, Coraline’s two complete worlds were brought to life,” says Selick. “Everything had to be thought out. It all had to be designed and signed off on.”

One of the first crew members to be hired was character fabrication supervisor Georgina Hayns, who had worked on Corpse Bride as head of armature and relocated from the U.K. to Portland. She comments, “It’s inspiring to be in a beautiful countryside and be creative. LAIKA affords you that, and the opportunity to experiment in a familial environment.”

Indeed, in her capacity, she heads up a crucial department, one that numbers over 70 people, and, she quips, “I look after the cast! It’s so joyful seeing them be brought to life by the animators.

“The difference between a puppet and a doll is that there’s more going on inside, and a doll can’t star in a stop-motion movie. Neither can hand puppets or marionettes.” To physically construct just one of the puppets for Coraline, 10 individuals had to work 3-4 months. Hayns elaborates, “All of our puppets are made up of silicone and foam latex and resin, and then inside they have their metal. Unlike marionette puppets – with whom everything is shot in real time – stop-motion puppets have to withstand a lot and last a long time; the Coraline shoot lasted over 18 months, following two years of pre-production during which our crews first started work. We work closely with the director on anything and everything that is going to be seen on-screen, and I am involved with every painting color or piece of hair going onto a puppet.”

She continues, “What comes first is, concept artists design the look of a puppet. Once it is approved, a sculptor turns that two-dimensional illustrated image into a three-dimensional object. The director has to discuss with us what performance he wants from that puppet. Next, it’s time to make the puppet. There are different forms of facial animation, and you have to decide if a particular puppet is going to have a replacement head and face – which is hard but with a soft mold — or a mechanical head and face, which is soft but with a hard mold.

“On Corpse Bride, they were mechanical. On this innovative production, we’ve gone much farther with the replacement technology and the puppets have smooth and expressive faces. It’s more sophisticated, what with the upper and lower parts of the face now being able to move so much more while also being secured with magnets. But there are a few characters in Coraline whose faces are mechanical – such as Father, Other Father, and Miss Spink – because it suits the characters.”

Selick notes, “Mechanical faces can still do very subtle things, but the replacement faces give you a wide range of expressions.”

Hayns adds, “It’s a bit like Swiss watch-making within the puppet head; the animator manipulates the character’s facial expressions. Eyebrows, jaw, lips – they are all adjusted. There are tiny joints within that move the heads and faces, whether replacement or mechanical.”

Having chosen which style of facial animation, says Hayns, “you must itemize the body of the puppet and work out what materials you will need to make everything from. The sculptor has to get the likeness right, sculpting the parts in clay and then separating them off. Then a mold-maker makes molds of all of those individual parts. We have a casting team to cast the materials that each puppet is going to be made from, and we have an armature team that builds the metal skeletons to go inside the puppets.

“A puppet for stop-motion animation has to have some kind of framework which will hold it up so that a human animator can manipulate that puppet and make it move. That framework usually has to be a metal one; wire, or perhaps armature – which is a ball-and-socket and hinge-jointed version of a human skeleton. The lead Coraline puppet has that. It all has to fit within the mold, of course; you can’t rupture that. It’s all adjusted as needed, with bolts and screws.”

Hayns notes that “our painters are like make-up artists; they work on literally thousands of replacement faces. One person will do all the lips on Other Mother for the last part of the movie; another will be responsible for her eyebrows, and so forth.”

Lead painter Cynthia Star found the replacement-faced Miss Forcible to be “the hardest puppet to paint. Her face has many powders, because Henry wanted her to look ashen. We painted her with a flesh tone, then highlights, then a yellow aging blush, and finally some lowlights for the bags under her eyes.”

For the character of Coraline, 28 different puppets, each 9 ¾” tall, were created. 9 changes of costume were needed for her for the story – and, as for any lead actor making a movie, duplicates of those outfits had to be kept handy. With animators handling the puppets thousands of times, there were at least half a dozen duplicates of each costume. Fragile body parts like Mr. Bobinsky’s hands – “despite the little wires we layer into the hands, these are the first things to break on any puppet,” notes Hayns – also had to be made many times over and kept at the ready.

Appearances can be deceiving; Mr. Bobinsky’s even more fragile-looking arms were in fact solidly supported by armature, and the flowing coat he wears in the Other World has wires in it so it could be made to billow on-screen.

For Coraline herself, Hayns reports, “Between myself, Henry and our lead costume design fabricator Deborah Cook, we came up with the look of her costumes, after first taking a survey of just what girls her age are wearing these days. Our teams went to Los Angeles, San Francisco, and London to try to find the right materials.”

Cook elaborates, “We started with images of regular clothing to see how we might want it to look. Then we researched fabrics and did color and fabric tests. For example, some fabrics would have a little grain or weave on them, which would be fine – but for the fact that a close-up on-screen would be distracting. Yet nothing was thrown out.”

Hayns adds, “Deborah’s department had to source the fabrics; for example, the lead Coraline we were using is 9 ¾ inches high. So, if you have a close-up of her, you have to know that the scale of that fabric is going to look right on her – and on the big screen in 3-D.”

Some fabrics proved highly adaptable; antique Victorian gloves offered the best – and thinnest – possible leather out of which to fabricate some of the dolls’ shoes, as well as Mr. Bobinsky’s boots.

Although there were no tall blue Russians available to reference Mr. Bobinsky, Cook notes that “we did have someone of comparable height and stature to an 11-year-old girl – which Coraline is – walk around in a raincoat so we could see how it hung and flowed, since it’s a key costume.”

The production’s painters worked on Cook’s group’s costumes as and where needed, whether to “age” them accordingly or provide detail like snow (made out of superglue and baking soda) melting on clothing. The hooded raincoat, once crafted with fabric and silicone and sporting an underlay of wiring, was ready for the rigors of the production process. But, unlike, say, the same one raincoat that Peter Falk wore and wore for years as Lieutenant Columbo, Coraline’s slicker had to be replaced regularly; hand-applied and hand-painted wear-and-tear was a safer bet than sustaining it for real.

Cook’s department is dotted with high-tech sewing machines and surrounded by sketches. As with other departments, she and her staff looked to real people to inspire the stop-motion characters they were working on; while referencing Teri Hatcher herself was an obvious choice for Mother, Wybie’s grandmother is meant to recall a jazz great.

Through this part of the process, the lead, or “control,” of Coraline and every other character has also been crafted to scale as a maquette –a puppet-sized detailed clay figure (though not a workable puppet) that can be found on mounts at the LAIKA workspaces. The maquettes serve as artists’ models, reference points of both character and look. “They are style and size guides,” says Hayns. “They solve problems for us in advance and can give us a real feel for the puppet before it is actually made.”

Another challenge for the Coraline moviemakers was creating the hair for the puppets. Selick wanted, for the first time in a stop-motion feature, the characters to look as if they had natural hair – instead of relying on the medium’s standard sculpted hairpieces. So the production experimented with various types of human hair, animal hair, and even tinsel. Hayns reports, “You find that human hair is too porous and does not stick. [Lead hair and fur fabricator Suzanne Moulton] hit upon using synthetic hair – mohair, actually – which we laid thin wires into. We also had to make different stunt wigs for the action that Coraline goes through.”

Moulton adds, “The tinsel worked for us, and with hair gel and glue it would stay in place. Coraline’s hair goes through a lot of handling on the sets, so we needed those replacement wigs. Our process for cleaning them was a little drop of alcohol and a gentle hand.”

Her department is perhaps proudest of one shot in the movie where Coraline leans down and looks under a bed. A special wig was created just for this brief scene.

Hayns says, “Meanwhile, our silicone casters had to make sure there were no seam lines on the puppets’ surfaces. We always have people on standby during shooting to repair a puppet whose silicone tears. They use magnifying glasses and get to work like a make-up artist.

“Here’s another trade secret; an eyebrow trimmer works well for treating the puppets’ hair.”

Cook adds, “In the costume department, we make good use of surgical tools and syringes!”

The various departments’ crafts were utilized across 52 different stages at the LAIKA studios. Though proportionally smaller than sound stages at a movie studio, they were nonetheless all up and running simultaneously at the height of production. Over 130 sets were constructed by hand to depict the various locations called for in the story’s two worlds.

Some of the sets were the same location in two different modes, on two different LAIKA stages, because they exist in both the real world and the Other World; for example, the family kitchen was not redressed for Coraline’s visit into the Other World, as would be the case on most movies. Instead, two kitchen sets co-existed – just as the two worlds do in the story.

As director of photography Peter Kozachik explains, “Visually, a strong sense of déjà vu permeates the story – a feeling of ‘I’ve seen this room before, but I haven’t been here.’ The features of both sets – the interior rooms, the fittings, the wallpaper, skies, and landscapes – had to be distinct yet somehow familiar. One world is ordinary, the other strange and whimsical.”

Other sets were unique to one world or the other, and were needed for extended periods of time; for example, it took 66 days to animate the Jumping Mouse Circus sequence in the Other World – all on the one set, with as many as 61 carefully choreographed mice on-screen at once.

Often, test sets based on designs by concept artist Tadahiro Uesugi were built and dressed with props. Kozachik would then light them and shoot some footage for Selick and the crew to look at, so that any adjustments and improvements could be made. Once everyone felt that everything was right and in place, only then was the set ready for shooting in and on. If a test set was on a smaller proportional scale, once it was approved by Selick the measurements were locked and recorded so that the set could be built to exact specifications. Though some test sets never make it on camera, they are nonetheless retained in the studio’s storage areas and are often checked for reference and specs during production.

Art director Bo Henry reveals that the largest-proportioned prop was the fountain interior of a snow globe. The “control” fountain interior is .5” tall, but to capture it for a crucial scene with Coraline, it was made to 4400% specification – or, 22” high.

In their full-service shop right near the stages, Henry and his department kept track of such details in binders cataloguing everything from storyboards to footage counts, as supplied by their LAIKA colleagues to them at weekly meetings. He elaborates, “When the storyboard for the scene calls for a close-up of a hand, you need to know the right scale. 100%, or ‘control,’ won’t work; you have to have a bigger hand ready — 300%? More? You may have to test out different sizes.”

After the sets are built, they have to be dressed; accoutrements like curtains or doorknobs are worked on by set dressers. As Henry notes, “We can deliver a full set, but if it isn’t dressed, then it’s just a big chunk.”

For the most complex sets and props – which Dakota Fanning admiringly calls “humongous” – the design had to incorporate a system of sliders, dials, motors, and needles with gauge marks. This allowed the animators to know how far to move the multiple elements for the necessary one-frame-at-a-time shooting. “Tie-downs” were built into sets and props so that the puppet(s) could be securely anchored with rods during the animation process.

In these instances, the animators could also work from underneath the sets, since many of the sets were built and situated on raised platforms. This also allowed riggers to send some props and characters into “stunt” sequences – just like on a live-action movie, albeit often tethered with piano wire rather than a full-scale harness or rig.

Wybie Lovat’s bicycle, a prop custom-made completely out of metal, “had a number of tie-downs,” notes Selick. “This was a prop that was on a set for about three months during the shoot, and nearly every piece was hand-made. The exceptions were the bike’s sprockets and chains.”

To create the fantastical foliage in Other Mother’s garden, animation rigger Oliver Jones utilized everyday materials including ping-pong balls (in/on the flowers) and wire.

Similarly, model maker Rebecca Stillman and lead mold builder Kingman Gallagher created a selection of distinctive cheeses out of rubber silicone. The silicone also became the increasingly long fingernails for Other Mother – “false nails built to scale,” laughs Hayns.

Knight notes, “We took a lot of our cues from the stage world, especially in the way that we built our sets and how we shaped and framed things.”

As in the stage world, sets were painted by hand and unexpected shadings were used; for example, shadows were enhanced by being painted in purple, rather than black. Even for Coraline’s drab everyday existence, Uesugi had provided the tip of blending pastels in. Audiences may not notice these subtle gradations, but they deepen the overall palette.

When Gaiman’s popular website hosted production-sanctioned early footage from the movie, the author notes that “what was interesting is that people stared arguing on some websites about whether it was computer-enhanced stop-motion – which it wasn’t. The puppets’ faces, their hair and their costumes’ fabric just moved so naturally.”

While hewing to the long-established tenets and aesthetics of stop-motion animation – i.e., crafting and moving just about everything by hand – the production did also bring the process into the digital age.

“We harnessed the computer to serve the process in a way that hadn’t been done in stop-motion animation before,” says Knight. “It’s a paradox; you now cannot really do a stop-motion feature without computers.”

This is in part because Coraline was shot with digital motion picture cameras. Storing each completed and digitally photographed frame on a computer allowed the animators to refer to a monitor and review their previous shots. This instant access allows any mistakes to be corrected on the spot. If there were none, then after checking the model with calipers animators will move the puppet and/or other elements infinitesimally for the next frame.

Kozachik was also the cinematographer on Corpse Bride, which was also shot digitally although not in 3-D. He reflects, “Film stock has never been technically perfect for shooting animation. One animated shot may go on for a whole week, and in the past you never really knew what you’d got until you saw what you’d filmed. Something may have moved on the set, or a tiny leak fogged the film, making the shot unusable. It’s only recently that digital imaging lets the crew and animators get instant feedback on their work and the lighting.

“Stop-motion is always going to have sharp edges and be more fanciful – and be accepted in that context. It has survived the computer-graphics phenomenon; the craft continues to thrive.”

Further advancing the process from an aesthetic standpoint, the animation in the final cut is sometimes two-frame or even three-frame, rather than always being one frame. This creates subtle nuances and ripples for characters and scenes.

Another key area where Coraline takes stop-motion into the 21st century is facial animation. Building on the replacement animation method originally developed by George Pal of “Puppetoons” fame –whereby each face is exchanged for another with a different sculpted expression in order to create the illusion of talking – Coraline marries traditional hand-made sculptures and drawings with CG modeling and 3-D printing to create a level of facial expressiveness never seen before.

Knight notes, “For the replacement animation, we model in the computer based on drawings created by a 2-D animator, and then print them out in rapid prototyping on 3-D printers – so you get the actual tangible upper or lower portion of the face. We then paint them all by hand – including, say, Coraline’s freckles – and place them gently onto the puppets. The result is beautiful and expressive facial animation. Coraline emotes, and you feel that you are watching a living, breathing girl.”

The rapid prototyping (RP) department is overseen by facial structure supervisor Brian McLean and facial animation designer Martin Meunier, and is an example of how the production is utilizing modern technology to bolster what is created by hand. Working from high-resolution scans and detailed resin castings of the hand-crafted original sculpts, the RP department’s classically trained CG artists build multiple replacement faces into the computer using key expression drawings as a guide, careful to retain every hand-sculpted detail and imperfection that the original sculpt possesses. In the final stages, these computer-“sculpted” faces are delivered as three-dimensional, printed objects. These objects are then cleaned, sanded, and painted by the hands of highly trained, detail-oriented artists. By respecting the sculptural integrity of the original sculpture, none of the characters lose the human touch that went into their creation.

Each machine is the size of a large cooler; three printers from Objet Geometries Ltd. – leaders in RP technology – were on call for Coraline. McLean notes, “It’s like ink-jet printing, but with something growing and growing in the space – and, instead of ink, a UV-sensitive resin is being used. The resin is liquid and it’s sprayed by eight heads in a given printer onto a water-soluble support material made of a plastic, which is the foundation for the entire process. There’s no residue and it’s such a solid support – so we are creating workable parts that fit and function together for the animators to manipulate by hand.”

Selick has long preferred going the extra mile with replacement faces, working with them rather than with mechanical ones on The Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach. McLean reveals that “with Coraline, LAIKA became the first company to do a feature-length movie using replacement faces printed on a 3-D printer.”

There is a bisecting horizontal line across the faces which divides them into the upper and lower replacement parts. The dividing line, fully visible during the production, is digitally erased in post-production so that audiences will never see it.

The result? While Nightmare’s Jack Skellington had 150 possible facial expressions, 16 years later Coraline has well over 200,000 potential ones. At one point in the movie, Coraline evinces 16 different expressions in a span of 35 seconds.

McLean is particularly pleased at the highly “articulated eye, and eyelid, animation that was able to be achieved – as well characters’ teeth being detachable, so they could be hand-painted and adjusted. All replacement faces or portions have an embossing system on the back which allows us to track them.

“Also, Coraline marks the first time that a stop-motion animation morphing sequence has ever been accomplished. The sequence runs for 130 frames, or nearly 6 seconds, and called for 50 replacements.” The sequence centers around Other Mother, for whom the animators took full advantage of the advances in eye and teeth animation that the RP technology spurred along.

McLean further clarifies that the department’s process “creates a range of multiple different replacement possibilities – everything from faces to props to animation sequences.” For Coraline, the first-ever replacement fire for stop-motion was successfully realized, with the printer working from images of real fire. “In a series of frames, you get a crackling fire,” marvels McLean. “It’s just one of the engineering feats that we’re now able to do for the art form that we weren’t before. We’ve made such advances in only 2 years.”

Also getting the RP treatment were silverware, doorknobs, door hinges, and Other Mother’s tempting food spreads. Coraline herself was RP’ed in a scaled-down (less than 100%) version, in her raincoat-and-galoshes ensemble. Other Father’s hands were RP’ed in different sizes for his piano-playing number. Also during that number, the puppet and his piano stool were hand-cranked from below, naturally creating the blur as he spins on his stool.

Whether hand-crafted or computer-created, images and / or sculpted models are given to the RP with an eye towards getting the tangible result. “While pre-visualizing from the data that’s been scanned in 3-D and then input, the RP computer physically breaks it down and then builds it up layer by layer. When it’s printed out, we can see how it feels and test it,” says McLean. This department’s work, too, must be approved before it is earmarked for inclusion in the movie; and, as ever, hand-painting must be done before any RP printout is ready for its close-up.

If the development in the RP computer is deemed successful, it is logged into a registration system that ensures exact consistency with the printout each and every time, no matter how many times the file is re-accessed. “That is the most important part of the replacement cycle,” states McLean.

Like stop-motion and 3-D, the RP process as deployed on Coraline is “really blending two different technologies,” notes McLean. “Cutting-edge starts it, and hand-made finishes it. A physical piece comes into the digital world — and then comes back out again as a physical piece.”

The process proved especially useful for making the dozens of mice for the Jumping Mouse Circus sequence in the Other World. Small as it might appear to Coraline and the viewer, many of the props in that scene were RP’ed at 200% — and the mice themselves, who required replacement faces and parts, were often RP’ed at 222%.

The most characters in a single scene in Coraline are the 248 individual (Other) Scottie Dogs, seen in the sequence where Coraline and Wybie attend a stage performance given by Miss Forcible and Miss Spink in the Other World.

With the aid of the RP system, all of these dogs were individually created; there is no computer duplication of the crowd, as is now commonplace in both animated and live-action features. The background dogs were operated on a mechanical system, attached to cranks that could be controlled by hand to move the figures in a pre-set pattern. Those dogs more in the foreground are wire-reinforced puppets that could be individually animated with movable joints – like the Scottie Dog that holds a flashlight in its mouth for usher duty.

Gaiman marveled at the sequence, which brings his dogs from the book to life and then some; “Every one of those little dogs could be moved up and down in their seats, or brought forwards or backwards. They are all moving – while there is flying-trapeze activity going on above. It left me astonished.”

Knight says, “Henry has his incredible visual sense, but he also understands motion and movement better than anyone I’ve ever worked with. He makes all of us around him better. He can look at something and say, ‘Shift that by four,’ and he’s exactly right.”

Animator Amy Adamy adds, “Henry has a strong vision and doesn’t compromise; he wants to get what he’s imagining up there on the screen. We’ll act out shots together, or he’ll draw a picture to convey what he wants.”

“For everyone involved in making a stop-motion feature, but especially the director, it’s an enormous task; you need to keep the big picture of story and characters in mind, inspire each other, and keep your mind on several dozen stages and hundreds of puppets,” Kozachik reminds.

Once the desired shot has been captured, the footage goes to the data wranglers, where it is coded and marked by digital systems supervisor Martin Pelham and his team. This way, anyone at LAIKA can call up footage on their computers at work for reference. The various departments also have access to binders itemizing each and every shot.

Crew members can access, on their computers, each catalogued frame that has been successfully photographed as well as – for individual characters like Coraline herself — specs on which replacement faces or parts were used for the shot. This is especially crucial for the animators maintaining consistency, whether from shot to shot or scene to scene. If an actor has recorded dialogue for a character, the sound bite (or, byte) can be called up as well.

Whether on the computer screen or in hand, the careful footage monitoring is another instance of how nothing is discarded but, rather, made use of as a learning tool and/or reference point.

Selick reflects, “As a kid, I did drawing, sculpting, photography, and music. Only when I got interested in animation did I realize that I could apply everything I knew.”

On the Set

A visit to the Coraline shoot at LAIKA’s Hillsboro studios — soon to be supplanted by an even larger campus facility in nearby Tualatin, as the company’s production schedule and employee roster expand – is a trip to a movie set like no other. Imagination is in front of you, in unexpectedly tangible form, at every turn.

The 52 different stages and the nearby offices, workshops, and storage areas span 2.5 acres within building space. Everyone working on Coraline is just steps away from each other, albeit sometimes traversing the length of a football field indoors.

Workshops are dominated not by posters or artwork but by tools of the trade; what someone is preparing at a given moment could be needed on a stage a few feet away a few minutes later.

Whether for Coraline or Townsperson #5, replacement parts and/or costumes are everywhere. Swatches for costumes are kept handy as well.

To a child, the workshops would seem to be the largest arts-and-crafts class imaginable. What looks like a tool kit instead holds an array of rapid-prototyping printer-generated replacement faces for Coraline that have been painted and finished by hand, with each upper or lower portion nestled in its own compartment. “Frown kits” or “smile kits” can be brought over to the stages as needed for a close-up.

One might be put in mind of a science lab, though assemblage is the priority rather than dissection. Great care is taken with what is being painted and crafted; powder-free latex gloves and hand sanitizer are always within easy reach.

A few yards away, through a doorway across a corridor, boxes of “Gobo Heads” signal that the sets are nearby. These are not more character face/head replacement parts, but rather grip / lighting tools that can be picked up en route to a stage.

Heavy curtains discreetly close off the dozens of sets, sometimes with a “Hot Set” sign signaling for extra caution when entering. While the nature of the movie means that “Quiet on the set!” does not really need to be said, a red light outside a stage indicates that it is currently in active use.

Some of the “Hot Sets” are in fact just that, needing to be cooled with portable air conditioners. This is so the characters and/or sets will not melt under the hot lights – and so the animators themselves won’t get overheated while working – during an August heat wave, for example.

There is a constant hum of activity as workers are on the move from one set to another. Once through the curtains, they move among artwork and standing props that are of museum-display quality, so detailed are the characters and creations. Instantly, anyone entering is part of the Coraline landscape; the fantastical is made even more so by being human-scaled on the LAIKA stages.

The Pink Palace, the house where Coraline and her family have moved to, stands life-sized relative to the puppets, as if it is a very large dollhouse. Like many a standing movie set, though, the interior is minimal and the structure has wooden supports; the Palace’s apartments and home interiors reside on other stages.

The Other World version of the Pink Palace looks even more enticing, like a model home; however, a peek behind its façade – while less dangerous than the one that Coraline takes in the movie –reveals supports, braces, and even clothespins shoring up the beautifully crafted prop.

Lunch hour for the entire unit begins @1:00 PM, during which there is indeed “quiet on the set” as the characters and props remain frozen in the middle of their last takes.

Night falls on some sets even during daylight hours, such as a night sky of star fields standing as a backdrop with the stars hand-threaded in. As per usual on Coraline, a computer has not generated the visual; handicraft has.

All told, the shooting areas span 183,000 square feet. The 52 different stages are the most ever deployed for a stop-motion animated feature.

Two Worlds, Three Dimensions

Offering audiences what Henry Selick calls “a fully immersive three-dimensional moviegoing experience,” Coraline is the first stop-motion animated feature to be shot entirely in stereoscopic 3-D during production.

The first 3-D stop-motion movie is acknowledged to be John Norling’s short film In Tune with Tomorrow, which was initially produced for an exhibit at the 1939 New York World Fair. The two processes continued on their separate tracks through the decades, each enduring as an ongoing part of motion picture history and movie magic. A few years ago, Walt Disney Pictures converted Selick’s 1993 stop-motion feature The Nightmare Before Christmas into the 3-D format.

After being consulted on the remastering process and seeing the results, the director and his longtime cinematographer Pete Kozachik approved of the conversion. The 2006 nationwide re-release in the new digital 3-D version was so successful that the picture has returned to theaters every fall since.

Selick reveals, “When I was making Nightmare and James and the Giant Peach, we did do a few experiments with 3-D. I’m friends with Lenny Lipton, who is at the forefront of the technology and now works at the leading 3-D company, RealD.

“Around 2004, I saw Lenny’s latest advances of stereoscopic imagery and Bill Mechanic and I realized that the 3-D experience would truly bring Coraline’s story and her two worlds to life. Since then, digital projection, the RealD process and its new stereoscopic glasses system have become more and more impressive – and the glasses are more comfortable!”

Neil Gaiman was also impressed. He notes, “The first time I saw a 3-D footage test on Coraline, my jaw just dropped. I had never seen 3-D look so good – and the sense of reality from the stop-motion animation made it closer to a live-action movie.”

Lipton has worked on exploring and refining stereoscopic 3-D since 1972. RealD Cinema is a high-resolution digital projection technology that does not require two projectors, unlike the older 3-D projection processes. RealD uses a single projector that alternately projects the right-eye frame and then the left-eye frame. Each frame is projected three times at a very high frame-rate, which reduces flicker and makes the image appear to be continuous. When viewed through the circularly polarized glasses, which allow each eye to see only its “own” image, the result is a seamless 3-D picture that appears to extend to all dimensions of the projection screen – and even beyond.

Kozachik notes, “3-D finally works with hardly any compromise, thanks largely to the digital projection – one lens, one projector.”

At Selick’s invitation, Lipton visited LAIKA to give a series of seminars about the newest stereoscopic technology, and the director admits that the production was learning as it went along. One of the most crucial elements to getting the 3-D right, he notes, is that “we would capture the essence of these miniature worlds and sets by shooting two pictures for each frame – a left-eye frame and a right-eye frame. Two pictures, but not two cameras.”

However, seven individual 3-D cameras were in use on a regular basis among the 52 different stages at LAIKA. Kozachik muses, “It’s the most complicated stop-motion shoot I’ve ever been on; there are twice the number of shots – about 1,500 – in Coraline that there were in Nightmare. You could say that there were seven second units and no first unit – or that there were seven first units. I would be there at the beginnings of a sequence and give notes on lighting and set adjustments – and then the unit would take ownership of what they were shooting. The monitors on the stages give everyone a good idea of what is going to end up on a movie theater screen.

“My priorities would be the stages which were just gearing up, or were ‘hot spots’ with issues. I learned to delegate a long time ago, and to ride a Razor scooter.”

Using a rig comprised of a single 3-D industrial camera, the same frame is shot twice on a stage before the crew moves on to the next frame. The camera is programmed to shift left and right, shooting separate frames for each eye and its frame. The choice of a “machine vision” camera, typically used by industrial robots and for inspecting factory parts, provided the moviemakers with greater flexibility with the camera moves and the freedom to move three-dimensionally around their subjects in close-up.

Another realization, notes Selick, was that “for 3-D, one would normally set the distance between the lens and its subjects in a given frame at what human eye-level distance is. But because we were shooting miniature puppets, we sensed that we should make the distance very slight.”

“We wanted to bring the viewer’s eyes closer together – more in line with how close together the puppets’ eyes are, so you can increase your sightline and be there in their world,” adds Kozachik. “We are able to present the audience with the same visual cues – eye conditioning — that they get in everyday life, stopping just short of anything that would make viewers cross-eyed.”

Selick says, “The technology of today’s 3-D really can now be called ‘stereoscopic,’ because audiences can now look at things with both eyes as we’re designed to do as human beings anyway.

Watching these movies now, we have depth perception. RealD captures the complete stop-motion world that we, the moviemakers, want to share with our audiences. With Coraline, we are using 3-D to bring audiences inside the worlds that we create, and convey the energy that our miniature sets exude for real. It’s about that, rather than having gimmicks like things flying off the screen all the time. We do have some of those, but sparingly.”

Kozachik adds, “Such moments support the story and were carefully scripted; short bursts, rather than lengthy set pieces. We were advised, ‘It’s more about opening up space, rather than bringing stuff up in your face.”

To that end, the cinematographer also invokes mantras from two of his mentors, Academy Award-winning visual effects artists Dennis Muren and Phil Tippett; respectively, “one shot, one thought” and “what’s the shot about?”

Happily, Kozachik found that “once you master the basics of stereo[scopic], it can be one more cameraman’s tool for you – so long as it’s not the only one. On Coraline, we also saw it as a storytelling tool.

“We have done some things with stereo – involving focus and depth of field – that we were told not to do, and to my mind they’ve worked out just fine. We didn’t want to drop the baton, but Henry and I have pushed things pretty far on this one.”

The two worlds in Coraline are both seen in 3-D; expectations might have been for the moviemakers to start the story in 2-D and then have audiences don their glasses once Coraline visits the Other World. But Selick felt that it would be most consistent to convey the differences in the moviemaking and storytelling. He notes, “In the world that Coraline lives in, we made the sets more claustrophobic. The color is more drained out, since her life should feel flat.

When she gets into the Other World, the sets may look similar but we built them deep and more dimensionally. We also tone up the color a bit, and move the camera more; in her real life, the camera’s locked and it’s like a series of drab tableaus. Her real life feels like a stage play. So the Other World feels more ‘real’ to her – and to the audience.”

Grooves were built into floors, and some walls were detachable– all so the camera could be moved, albeit only millimeters at a time. To better identify viewers with Coraline’s vantage points, the camera was usually situated below adult eye-level.

The painstaking detail and beautiful lushness of the moviemakers’ work is maximized in 3-D, although the movie can be converted to 2-D film or digital prints (like regular movies) as well. But, while Coraline can and will be shown in 2-D at some theaters, Dakota Fanning enthuses, “It looks so much better with the glasses!”

The actress speaks from experience; at one screening of finished footage, she briefly raised her glasses to peek at the screen and confirm her hunch that she would best experience the movie with them on.

Further, she adds, “It’s rare to see a movie that you can watch over and over again and find new details each time.

“I’m proud to be a part of it, and I will have this movie forever to show to my children.”

Fast Facts

Coraline is the first-ever stop-motion animated feature to be conceived and photographed in 3-D

The Coraline shoot lasted over 18 months, following 2 years of pre-production

More than 20 people relocated to Portland from other parts of the U.S., and even from abroad, to work at LAIKA’s studios on Coraline

Over 130 sets were built across 52 different stages at the studios; spanning 183,000 square feet, the 52 different stages were the most ever deployed for a stop-motion animated feature

To construct 1 puppet for Coraline, 10 individuals had to work 3-4 months

For the character of Coraline, there were 28 different puppets of varying sizes; the main Coraline puppet stands 9.5 inches high

At one point in the movie, Coraline shows 16 different expressions in a span of 35 seconds

There were a total of 207,336 possible face combinations for Coraline

There were a total of 17,633 possible face combinations for Mother

Coraline marks the first time that a stop-motion animation morphing sequence has ever been accomplished; the sequence runs for 130 frames, or nearly 6 seconds

The on-set 3-D photographic process for Coraline entailed shooting two pictures for each frame – a left-eye frame and a right-eye frame – with the same camera

It took an entire week of production, with a crew of over 300 people working on 52 stages, to complete 74 seconds of footage

There are 248 Scottie Dogs in the audience with Coraline and Wybie watching the stage performance

The Jumping Mouse Circus sequence had as many as 61 carefully choreographed mice on-screen at once • 40 trees were handmade for the orchard setting

1,300 square feet of fake fur was applied to stand in for live and/or dead grass

The garden lilies were silicone thimbles turned inside out and then hand-painted • The on-screen snow was made from superglue and baking soda

At the center of the flowers in the fantastical garden are ping-pong balls