Tagline: All you need is love.

At once gritty, whimsical and highly theatrical, Revolution Studios’ Across the Universe is a groundbreaking movie musical, springing from the imagination of renowned writer director Julie Taymor, and and writers Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais, that brings together an original story and 33 revolutionary songs – including “Hey Jude,” “I Am the Walrus,” and “All You Need is Love” – that defined a generation. Taymor says, “The idea was to create an original musical using only the songs of the Beatles.”

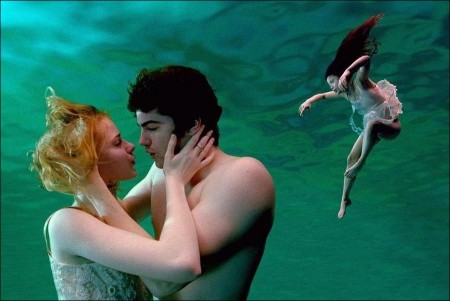

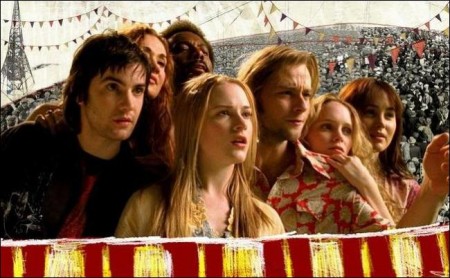

A love story set against the backdrop of the 1960s amid the turbulent years of anti-war protest, mind exploration and rock ‘n roll, the film moves from the dockyards of Liverpool to the creative psychedelia of Greenwich Village, from the riot-torn streets of Detroit to the killing fields of Vietnam.

The star-crossed lovers, Jude (Jim Sturgess) and Lucy (Evan Rachel Wood), along with a small group of friends and musicians, are swept up into the emerging anti-war and counterculture movements, with “Dr. Robert” (Bono) and “Mr. Kite” (Eddie Izzard) as their guides. Tumultuous forces outside their control ultimately tear the young lovers apart, forcing Jude and Lucy – against all odds – to find their own way back to each other.

Investigating the 60’s

Julie Taymor, the groundbreaking visionary behind Revolution Studios’ new film Across the Universe, says that she first conceived a film that would, in her words, “investigate the ‘60s. It had to penetrate all levels of the Beatles’ songs. From the love songs to the political songs, the music and the film would not just reflect the microcosm of a character’s experience, but, from my perspective, would also represent the macrocosm of the events that are happening in the world.”

For Taymor, though the film is set a generation back, making the story and the film fresh and alive for today’s audiences was the entire point. “I really want young people to see the passion in this movie – to see with what fervor these characters invested themselves into social movements as well as self-exploration,” she says. “I hope it really speaks ‘across the universe’ and across cultures… that anybody could identify with the situations and the events that are happening in this movie.”

According to producer Jennifer Todd, the film is an artistic statement from Taymor. “In addition to being a unique voice, Julie is the hardest-working director I’ve ever worked with,” she says. “It’s an amazingly satisfying experience to work with someone who lives and breathes the movie morning, noon, and night. One particular weekend, we went away and came back to discover that an entire new sequence had been invented. Because she’s like that, she attracts people who want to work just as hard to achieve her vision.”

Producer Matthew Gross, who generated the project, concurs. “Julie is a national treasure,” he says. “She is a true artist – not only does she bring visual appeal, but she has just the right touch with the singers and dancers, which was so necessary for this film. The work she did in Titus and Frida show her incredible vision. In addition, because everyone wants to work with Julie Taymor – and with good reason – she is able to attract top artists and amazing talent to work with her. She is a tremendous asset to the film in every way.”

Unlike most musicals, where a story comes first and songs are inserted in at key points, the songs created the story. “Beginning with over 200 songs written by the Beatles, we eventually chose 33 that we felt best told the story of a generation and a time,” says Taymor.

Todd explains, “The film is an original musical and it has an original story – one you’ve never seen before, inspired by Beatles’ music in a way that you haven’t heard before.”

“The entire concept of this musical,” Taymor explains, “is that the lyrics will tell the story. They are the libretto, they are the arias, they are the emotion of the characters.”

Although Taymor was only in her early teens in the 1960s, the story was inspired by her childhood observations: “Lucy and Max, the brother and sister, are modeled slightly after my own older brother and sister, and I’m Julia, the young girl who’s watching. During that time, I was a voyeur to what my parents were going through with teenagers and then college students who were going through the radical political movement: the draft, the hippies, the drugs. And so I was there – I didn’t get immersed myself, but I watched it.”

Taymor admired the outspoken spirit of the time. “People really took chances,” she says. “As Lucy says, ‘I’d lie down in front of a tank if it would bring my brother home from the war.’ And of course Jude responds, ‘But it wouldn’t,’ and she gets upset and she says, ‘Does that mean you don’t think I should try?’ I’m so moved by the fact that at that time, people would try.”

But Taymor definitely did not view the project as a piece of nostalgia. She notes that many of the issues facing young people in the ‘60s are still very relevant today. The filmmakers’ goal was to translate the passion and feeling of the 60s and have it resonate in a way that made it feel as contemporary as possible. The reason to make a film like this, in her mind, was the immediacy of the themes. “You constantly have to revisit these stories in order to reflect upon your present and really think, ‘What is it that’s different now?’” Taymor says. “That era is explicitly important to our time now.”

In order to bring the era to life, Taymor and screenwriters Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais created an entirely new story, using the songs to guide their way. “Characters were created for the songs,” Taymor continues. “For example, the character Prudence: I loved the idea of taking ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ and giving it to an innocent cheerleader in Ohio.”

The song begins with the young girl singing plaintively on the sidelines of the football field. “We don’t change the lyrics,” says Taymor, “but partway through, you realize she’s not in love with the quarterback – she’s in love with the blonde cheerleader. All of the sudden the song works in a totally different way, because it’s about repressed love.

By the end of the song, this young girl, who doesn’t even know what she’s feeling, leaves home. She hitchhikes her way to New York City. Without having to go into the background of the character, without having to see her mother and her father and her life story, the song says it all.”

“As we went through the journeys of characters, songs came up,” Taymor continues. “In the story, Max is going to be drafted into the Army. I went through dozens of songs until finally I got to ‘I Want You’ and it registered in my head, ‘My God, “I Want You,” isn’t that the Uncle Sam motto?’” It was a perfect fit. As the story began to grow, in this organic way, Taymor would follow the songs where they led her. In many cases, the songs would move to other characters and take on multiple meanings, as in the case of “I Want You,” which starts with Max’s army induction and continues to a more erotic scene between the characters of Jo-Jo and Sadie. In some cases, the songs seemed more like private moments, and in the manner of an aria in an opera, expressed inner thoughts.

In still other cases, like “Revolution,” the directness of the lyrics led them to portray the emotion of a scene in a stronger way than dialogue could. “When Jude sings ‘Revolution,’ he’s actually breaking into the Students For Democratic Reform office, going right up to Lucy, and using the emotion of the music and those lyrics to express himself instead of saying it just with straight dialogue,” notes Taymor. “He keeps singing because he’s in a state of being that is beyond the everyday; he’s in a heightened state that’s going to get him beat up and thrown out by the end of the song. It really helps us encapsulate time, because the music helps you to go very quickly through an emotional state and get to another level that is very, very heightened and very dramatic.”

About the Cast and Cameo Performances

With the characters created from the raw material of the songs, the filmmakers placed an imperative on choosing the best actors and singers they could find for the roles. As a result, the only cast member with major film experience is Evan Rachel Wood.

Taymor notes, “She’s so young and nobody really has seen her grow into a woman – in this movie, she grows into a full-fledged adult, serious woman. She’s going to be a major discovery for people. Plus, no one even knew she could sing.”

Among all the songs she sings in Across the Universe, the one she looked forward to most as the greatest challenge was “If I Fell.” “I’ve never had any training in singing, and that song goes very, very high. It’s also the most emotional song I sing. So I had to prepare myself emotionally for the character at that moment and also put it into song – while also remembering what my voice had to do,” says Wood. “As I was learning the song and trying to figure out how to sing it, they brought Jim Sturgess into the room so I could sing it to him. It was the very best I ever sang it – it took my mind off what I was doing and freed me up.

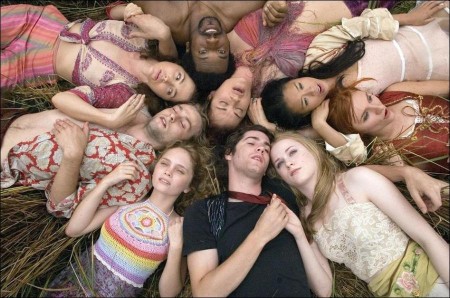

Wood notes that she shared not only a connection with Sturgess, but with the entire cast – and that it was reciprocal. “Julie knows how to cast a movie,” she says, “and she knew that we would work well together because we’re all very similar. During production, I’d felt like I’d gained brothers and sisters; they’re all such interesting people and they all have great life stories.”

Open casting calls were held in England for the role of Jude. Taymor said she could tell from a tape of Jim Sturgess that he was the one, even before she met him in person.

Taymor and her longtime collaborator, composer Elliot Goldenthal, were very particular about what kind of voices they wanted, she explains. “We did not want musical theater voices, and we didn’t want pop-y voices. Jim just fit in right away. Jim’s been in a rock band and he’s an actor. He just sings with such an incredible ease that you feel that the character is talking just to you. He has a beautiful voice – and there’s no disconnect between when his speaking voice and his singing voice. Jim can go right from talking to singing.”

Sturgess says that he is fortunate to be making his major-studio debut in Across the Universe and to be working with no less a talent than Julie Taymor. “She’s brilliant,” he says. “She’s an endless head of ideas. She has a definite idea of what she wants to see, but also allows her actors the room to bring their own ideas – she just takes it all in.”

Working with the stars playing the cameo roles in the film was also an eye-opening experience. “One day, I was sitting around, watching Bono sing ‘I am the Walrus’ – so I was already having a good afternoon – and then he comes over and asks me if I’d like to come to his show at the end of the week. What was I going to say? ‘Sorry, I have other plans?’ No, I stood there and said, ‘I’d love to, thank you… Mr. Bono.” Another highlight for Sturgess was the day Bono came to set and told the young actor that he liked Sturgess’s voice.

Max is an American, but Taymor did not find an American actor that had the qualities she wanted for the part. When she met Joe Anderson, another Brit, she found it interesting that he did not even want to audition for the role of Jude: “When I went to London he auditioned for me, but he said, you know, “I’m not that character – I am Max,” so even he knew that his own personality would be better suited to that. And he looked like Evan, so he was really the right mix to play her brother.”

For Sadie, says Taymor, “I knew Dana Fuchs and I created the part for her. Dana had done a demo for Elliot for another project, and she has that voice that you haven’t heard since Janis.”

Fuchs says, “I felt like I was in a movie when I was on the phone with Julie and she was telling me that I got the part. There was no one there to witness. I was shocked – on top of getting the part, to find out she wrote it for me was amazing. She said there was no other Sadie.”

Sadie’s partner in the movie is the character of Jo-Jo, who is also a musician. “He comes from Detroit, comes from soul music, and hooks up with these young strays and he becomes part of Sadie’s band. He transforms in front of you, going from the slickedback hair to the wild afro.” To play Jo-Jo, Taymor called upon Martin Luther McCoy, a singer and a guitar player in New York without much acting experience. Taymor says that he proved himself to be “a phenomenal actor” as well as musician.

T.V. Carpio, who plays Prudence, was another discovery. Along with having a beautiful singing voice, T.V. is a dancer and former ice skater. “I had Prudence become a skating horse in the circus scenes because she could ice skate. Then, I thought, ‘Well, she’ll be the cheerleader, instead of just watching the cheerleader, because she’s so good physically,” says Taymor. “As you get to know the actors, you create more and more for them.”

The feeling was mutual. Carpio recalls, “As Jim said to me, in the very beginning: ‘I’m just desperate to do what Julie needs from us.’ We wanted so much to make her vision come alive. When she would tell us what she saw, it would never be just what’s written on a piece of paper – it would be something just completely out of this world… we were so honored to be a part of that. We couldn’t even believe that this is our job.”

Wood agrees. “Julie really brings out the best in you,” she says. “She can make you do things that you never knew you could do. I love how she brings that out of people. You can’t be afraid and you can’t have any fear. She throws you into the deep end and somehow you’re just in there and you swim there, and you realize, ‘I didn’t know I could do this.’”

The cast was rounded out with some very special guests in supporting roles. Bono, who was in the middle of a world tour with U2, managed to fit in two days on set as “Dr. Robert.” He played Madison Square Garden late into the night before each of his early morning calls. “We concocted the character together, me and Julie,” says the rock star, activist, and first-time actor. “She wanted him to be true to the time and period, so we made him a west coast, Neal Cassady type.” Cassady, of course, was the inspiration for Jack Kerouac’s On the Road; a key figure in the 60s counterculture, he was also an author in his own right and the driver of Furthur, Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters bus).

“We studied film of him and the way he worked, and it’s almost like he wanted to be a rock star – he has all these jerky moves, a lot of self-confidence, always plays to the women in the room. For my first acting role, I thought this would be interesting and a little bit special.”

Salma Hayek, Taymor’s friend and Oscar-nominated star of Frida, plays the sexy dancing nurses in “Happiness is a Warm Gun.” Taymor asked Hayek if she wanted to play a nurse and Hayek said she wanted to play all five of them – something that was accomplished with motion control camera work (requiring Hayek to repeat her dance number very carefully many times during two long days in order to create the illusion of five pin-up nurses). Eddie Izzard plays the role of the circus ringleader in “Being For the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” and Joe Cocker worked in the middle of several nights to complete his multiple “Come Together” roles of singing bum, pimp, and hippie.

Reinterpreting the Songs

In addition to having a story that was layered enough to do justice to the songs, the other key element to the film was the musical interpretation, says Taymor. “It was really scary having the legacy of the Beatles’ music on your shoulders, because it’s the Holy Grail,” she says.

“It’s so important to so many people, and the originals were perfect. We knew from the beginning that we did not want to compete with the Beatles’ versions,” says Taymor. She felt that the best way to honor the band was to have their songs be the heart and the star of the film, emanating right from the characters.

To interpret the music, Taymor relied upon a trusted longtime collaborator, Elliot Goldenthal. “Though Elliot is a composer and there are no songs to be composed, his arrangements and his understanding of drama and character are so great. I’ve worked with him for twenty years and have total trust and admiration for his work. I knew that he would find a new way to interpret the songs; by placing them with new arrangements, the music would be fresh again – not a better version, but different.”

Goldenthal and Taymor also brought in renowned rock music producer T Bone Burnett and producer Teese Gohl, who has worked with Goldenthal as a music producer on more than 20 films. Goldenthal, Burnett, and Gohl collaborated on producing the music. Every song was analyzed: who would be singing, what was the content, the feeling needed from it in the film, and the time period.

Goldenthal notes, “Everybody knows the Beatles’ music so well, it’s almost like a ghost in the room. All the licks that they played, the specific guitar fills, the drum fills – everybody fills those in when they hear the songs. The songs were done perfectly already by the Beatles – they are definitive performances. So the challenge was try to find an honest way – staying within oneself – of getting to the core of these songs and try to find other ways to support the beautiful words.”

To give the music authenticity, the team recorded many of the songs using period appropriate equipment, such as analog tape and vintage microphones. Gohl recalls, “We were all on the same page in taking this approach and in our desire to avoid the digital pitfalls.”

As for working with the Goldenthal, Gohl says, “Elliot is unique in every sense, but to see him as a rock ‘n’ roll producer is yet another mind-blower.”

It was not enough, of course, merely to come up with new arrangements for the songs. Because the lyrics of the songs tell the story of the film, it was crucial to Taymor that the performances have immediacy and relevance to the scenes around them. With that goal in mind, the filmmakers decided to make the movie with as much live singing as possible. She gives credit to another one of her team members, sound mixer Tod Maitland, for making it work.

“He’s another genius,” says Taymor, because “most of the movie is live.” Maitland, who is a three-time Academy Award® nominee, had most recently worked on the more traditional movie musical The Producers, but Across the Universe would require an entirely different approach. He explains why such a radical move was necessary: “In most musicals, the actor speaks and then they go into a singing voice.

For most people, a singing voice is an entirely different voice – something they did in a studio two or three months earlier. It takes you out of the film. On Across the Universe, we wanted to keep the environment real. When you transition from speaking to singing, we want those moments to flow free, so that you don’t go in and out of different sound qualities – you want to stay in the scene. In addition, because the lyrics serve as dialogue in this movie, you want to hear the little bit of bounce off the walls, you want to hear people moving around. You don’t want a very closed-in, studio sound.”

The actors began the process by pre-recording their songs; these would to give them an idea of how their performance would go and provide a back-up for the editing process. In these sessions, the actors each performed the songs on three tracks: the first a studio microphone, the second a boom mike, like the one used on set, and the third a “lavalier” mike, also used on set.

During the shoot, the set would have to be extremely quiet to record a live vocal performance. The actors were all fitted with tiny ear pieces, called “earwigs,” to enable them to sing along with their pre-recorded performance. The pre-recorded track would give the actors a guideline to follow and allowed some freedom in the sound editing, according to Maitland. “If an actor turns his head away and goes off mike, we could pull in a vocal pre-record and lay that over. Or if there’s some noise over a take that the filmmakers really loved, we could go to a vocal pre-record.” However, he stresses, those are the exceptions. “The design of the whole film is to use live vocals as much as possible.”

The somewhat tricky process was made easier by the cinematographer, Bruno Delbonnel, and his lighting designer, John DeBlau, who consulted with the sound department when placing their lights, in order to help them to keep the boom microphone as close to the actors’ heads as possible. For the optimum result, the mike had to be only 12 to 15 inches from the actor, the same distance used in the prerecording sessions.

About the Production

Across the board, Taymor attracted an exceptional team of collaborators for Across The Universe. In the key role of cinematographer, she chose Frenchman Bruno Delbonnel, who although he has just begun shooting films in the US, is already a two-time Academy Award nominee.

Taymor recalls: “Bruno, in our first interview said, ‘I hate musicals.’ I thought, ‘Now what do I think about that? That’s interesting.’ And I thought, he’s done Amélie and A Very Long Engagement, these incredibly theatrical movies. He has an incredible sense of light and photography. I knew that tough, European sense with him: he would want it to be a serious movie, not fluff; that the darkness would be there when I wanted it to be there, but it would also have that whimsy and theatricality that was very important.”

Mark Friedberg (Far From Heaven, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, The Producers) served as production designer. For Friedberg, it was a special opportunity to work with Taymor, a director who happens to be one of the most creative theater designers of our time. He notes, “Julie Taymor has dreams that are better than anything I could ever design.” Taymor came in one morning and described to him the image of Vietnamese women dancing on the water as part of the montage for the song “Across the Universe,” which she had dreamt the night before. “That is not fair,” he laughs. “I want to be able to do that.”

Friedberg says that Taymor’s greatest strengths are that “she is brave and she is committed to following her ideas to their fullest. She is not afraid that they might fail.” In fact, he says, her only fear is not going far enough. “She is afraid that our ideas might not be interesting, or that we are not trying hard enough, or we are not challenging ourselves enough. It’s an amazing and inspiring way to work.”

As a result, Friedberg says, his greatest challenge on Across the Universe was not the technical process of realizing Taymor’s vision, but living up to her expectations of creating a wholly new and original work. “She let me go and get way out there and see if I would find anything she would like, and usually the stuff that was farther out was the stuff she was curious about. I wanted to interpret the 60s in a way that was relevant and interesting. I didn’t want to re-create it – I wanted to reinvent it.”

So while Friedberg’s art department began with a tremendous amount of historic research, he also had a bit of artistic freedom to reinterpret the 60s, and pull in other influences. Friedberg and Taymor looked at a lot of graffiti art from the 80s until present day for inspiration for Jude’s art and a lot of the downtown East Village neighborhood.

An example of how the production design would sometimes “reinvent” the 60s was Dr. Robert’s “magic bus.” As Dr. Robert is inspired by Neal Cassady, the real-life figure who drove Ken Kesey’s famous bus Furthur, that bus became the starting point for the design; however, Taymor thought it looked somehow old. She loved Friedberg’s “Basquiat-inspired,” cool, contemporary version. Graffiti art is not true to the period, but Taymor preferred its slightly rougher, street edge to the sweeter and more flowery, more stereotypical 60s look, and it became a useful design element.

“As a designer herself, she has a very keen visual sense,” Friedberg continues. “She has a very powerful aesthetic. She’s operatic. She’s also a collaborator. She asks ‘What do you think?’ and she is always open to the best idea in the room. We had an easy vocabulary. Julie would say, ‘For the circus, I want to use a Matisse palette,’ and I knew exactly what she was talking about.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Friedberg was most anxious about one part of the production: the film’s large-scale puppetry. He went to an expert puppet designer, Paul Rice, a top puppet maker from the theater, who had built 15 of the Pumbaa puppets for worldwide theatrical productions of Taymor’s “The Lion King.” Rice and his crew would make small maquettes of the puppets to show Taymor and she would give them her feedback, with very specific instructions on color, shading, and movement.

For the circus scenes – which take their inspiration from the radical Bread & Puppet Theater, founded in the 60s in New York City – Rice would carve a puppet for about two days before a crew of about 13 people began the process of painting and paper mâché. Two of the largest puppets they built were an 18-foot-high face at the circus and a 27-foot-tall walking man at the peace march. The giant arms and hands in the circus spanned 120 feet.

One other key design challenge would be finding a visual look and for Jude’s work. A member of the art department crew named Don Nace became the source of Jude’s artistry. Friedberg had used Nace on his crew before, but was not even aware of the scope of his work until someone in the art department suggested he check out Nace’s website. Taymor liked his work the best and so the important character of Jude’s art was cast from within the crew. Jim Sturgess, the actor who plays Jude, worked alongside Nace in a studio, in preparation for the scenes (like “Strawberry Fields”) in which Jude is working. “Don would give me little tasks to do each day… We would sit and listen to Tom Waits records and he would just sit in the corner, kind of sketching and drawing and give me little things to do.”

The induction center and the VA hospital were two of the most unique stage sets. They are “bookends of the Army experience,” says Friedberg. “We made it very olive drab, black and white. Julie wanted a mechanized experience for the induction. Even the sergeants are very robotic.” During breaks in filming, the dancers playing the sergeants broke up the menacing scene by using the conveyor belt set as a “catwalk,” with each trying to do his best runway model impression while wearing full prosthetic makeup.

The induction center is one of the moments that is a true abstraction from reality, which turns into more of a musical number. Another was “Happiness Is A Warm Gun,” which takes place in a round hospital room (and features a cameo by choreographer Daniel Ezralow as a possessed dancing priest).

“I thought it was cruel to make the guys all look at each other,” says Friedberg. “So we made the room round. This was also a historic reference to old tuberculosis wards; when they were built in Victorian times, scientists believed that germs lived in corners. So if you had a round room you had no corners – you had no germs. On top of that, we had the idea that maybe the room would spin – the song would be stronger than gravity. It was one of the first discussions that Julie and I had.”

Another key member of the production team was legendary costume designer Albert Wolsky (an Academy Award winner for Bugsy and All That Jazz, and an Oscar nominee for three more films).

Wolsky explains that his greatest challenge was dressing the nearly 5,000 extras in the film. “Anybody who has a non-speaking part, every single one, all have to be dressed from head to toe. We did mass fittings five days a week with teams of fitters,” he says.

But even while dressing the masses, every detail is crucial, says Wolsky: “Without the right hair and makeup, the clothes won’t make any difference. You have to find ways to capture the period without making it too costume-y. I wasn’t out to make a costume ball. I wanted to make it like real clothes, but also to have this feeling of some other time.”

He continues: “What makes it interesting for me is that the beginnings are all very specific. Jude comes from Liverpool, so that’s one look. Jo-Jo comes from Detroit, that’s another look. Max and Lucy come from the Massachusetts area, that’s another look. And they all converge onto New York and the Village.”

* * *

Most of Across the Universe was shot on practical locations – over 50 locations in 60 days, mostly in the New York City area. Coordinating this complicated shoot was First Assistant Director Geoff Hansen, who says, “Julie is one of the most creative, artistic directors I’ve ever worked with in my life. She’s got a vision that blows me away. She’ll have this image, say, of Vietnamese ladies floating in a lake with masks next to them, and I’m the guy who has to figure out how to get the crew up there and shoot it and where we’re going to eat lunch and everything else involved with executing that idea.”

Location manager Rob Striem notes: “On a lot of films you have a few locations where you can settle in and get comfortable. On this film, every single set was one, two or three days at most, so we were constantly jumping around.”

Many of the sets that would be shot for only a couple of days required two-to-four weeks of preparation. Every day that the crew was shooting on one set, they could be simultaneously prepping four other sets and striking two that were completed – all over New York City. And this work was not simple work, like painting walls and dressing a living room, says Striem, but “making the South Bronx into Detroit, dealing with 50 active businesses.”

Indeed, the film company created so many different worlds – Detroit, Vietnam, Washington D.C., suburban Massachusetts, Muscoot farm, where they staged the circus, and other “magical” environments – all within the New York City area. Rivington Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan was one of the biggest locations for the film. The hip and artsy neighborhood was transformed into a heightened version of the East Village scene in the 1960s.

A few real businesses from St. Mark’s Place that actually existed were portrayed, but the art department mixed it up and made the area more colorful and exaggerated than anything that was really in New York at the time. Much of the Rivington Street set was actually inspired by the Haight Ashbury district in San Francisco, says Friedberg. “There’s probably not too much in that location that did not exist somewhere, but it did not exist all together. We made an impressionistic collage of the world of youthful self-expression.”

The set stretched for three blocks; from Attorney Street to Norfolk Street on Rivington, then a half block North and South on Clinton Street. The Rivington / Clinton intersection was the major crossroads, where the dancers would do their “Come Together” number and several other scenes were staged.

The neighborhood was extremely supportive of this psychedelic explosion. The local newspapers encouraged people to drive by and check out the sets while they were still up, and after filming was completed, several neighborhood restaurants chose to leave up the colorful paint and murals.

A similar thing happened on lower Fifth Avenue, near Washington Square Park, where a peace march set to the song “Dear Prudence” was filmed. Area residents wanted to leave up the peace symbols and anti-war banners. It was another moment where the 60s and the present seemed to come together, so to speak. Similarly, the art department found that they did not have to create mock newspaper stories for set dressing: they took current newspaper articles about Iraq and changed the names in the headlines, and found they worked perfectly for Vietnam stories.

As for the actual Vietnam scenes, the production staged them in one day in Moonachie, New Jersey, in a swampy area out near the Meadowlands Arena. The production also went to New Jersey to shoot “A Little Help from My Friends” at Princeton. In these scenes, Joe Anderson got the chance to perform a little stunt work, firing a gun in the Vietnam sequence and sliding down a 35-foot-high marble staircase at Princeton.

The South Bronx became the Detroit riots, again a massive undertaking for a shoot that was only one day. The production picked a block that New York City has plans to raze, so the challenge was to make one side of the street that was entirely abandoned look occupied. The Detroit scenes required 20-25 stunt people, explosions, and stunt guys on rooftops firing guns. For Jo-Jo’s little brother’s funeral, Taymor wanted a cemetery that was adjacent to a church but entirely surrounded by concrete in an urban setting. The production laid sod in a parking lot and created the cemetery, since nothing like that existed.

Washington D.C. was also staged in uptown Manhattan, at Grant’s Tomb, and the Columbia University student riots worked out well at the Museum of the City of New York.

During filming, Wood and Sturgess coined a phrase to describe the sometimes overwhelming nature of the project. “Jim and I had this joke – we’d call it an Across the Universe moment, when we would stop and we really think about what we’re doing,” says Wood. “It would make us cry.”

Wood had that experience early in the shoot, doing “Let It Be,” the funeral scene for her high school boyfriend. They had already shot the scene where the soldiers come to the door and tell them Daniel has died; “I thought I’d gotten it all out then,” says Wood.

When they came to the day of the funeral, “I knew it was a hard scene for Lucy,” she continues, “but I wasn’t really going to break down or cry or anything. And then they said ‘action’ and they started playing ‘Let It Be’ and they started folding the American flag in front of me, and I don’t know what happened, but I just completely broke down; I just couldn’t contain it. Listening to the song, I thought, ‘This is probably going on right now; people are still seeing this every day, and people still have to fold these American flags in front of these families.’ It just killed me. This movie has just had a really big effect on me in that way.”

Production notes provided by Columbia Pictures.

Across the Universe

Starring: Evan Rachel Wood, Jim Sturgess, Max Carrigan, Joe Anderson, Dana Fuchs, Martin Luther, T.V. Carpio

Directed by: Julie Taymor

Screenplay by: Dick Clement, Ian La Frenais

Release: September 21, 2007

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some drug content, nudity, sexuality, violence.

Studio: Columbia Pictures

Box Office Totals

Domestic: $24,343,673 (82.9%)

Foreign: $5,023,470 (17.1%)

Total: $29,367,143 (Worldwide)