Hulk Movie Production Notes (2003)

Scientist Bruce Banner (Eric Bana) has, to put it mildly, anger management issues. His quiet life as a brilliant researcher working with cutting edge genetic technology conceals a nearly forgotten and painful past. His ex-girlfriend and equally brilliant fellow researcher, Betty Ross (Academy Award winner Jennifer Connelly), has tired of Bruce’s cordoned off emotional terrain and resigns herself to remaining an interested onlooker to his quiet life.

Which is exactly where Betty finds herself during one of the early trials in Banner’s groundbreaking research. A simple oversight leads to an explosive situation and Bruce makes a split-second decision; his heroic impulse saves a life and leaves him apparently unscathed — his body absorbing a normally deadly dose of gamma radiation.

…And yet, something is happening. Vague morning-after effects. Blackouts. Unexpected fallout from the experiment gone awry. Banner begins to feel some kind of a presence within, a stranger who feels familiar, slightly dangerous and yet darkly attractive.

All the while, a massive creature — a rampaging, impossibly strong being who comes to be known as the Hulk — continues its sporadic appearances, cutting a swath of destruction, leaving Banner’s lab in shambles and his house with blown out walls. The military is engaged, led by Betty’s father, General “Thunderbolt” Ross (Sam Elliott), along with rival researcher Glenn Talbot (Josh Lucas), and both personal vendettas and familial ties come into play, heightening the danger and raising the stakes in the escalating emergency.

Betty Ross has her theories, and she knows the shadowy figure lurking in the background, Bruce’s father, David (Nick Nolte), is somehow connected. She may be the only one who understands the link between scientist and the Hulk, but her efforts to stop the military threat, deploying every weapon in its attempt to capture the monster, may be too late to save both man and creature.

Acclaimed Oscar-winning filmmaker Ang Lee (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) turns his masterful eye to adapting the classic Marvel Comics character for the big screen. Setting out to faithfully transfer the Hulk comic book character from four-color paneled page to motion picture screen, Lee combines all the elements of a blockbuster visual effects-intensive Super Hero movie with the brooding romance and tragedy of Universal’s classic horror films. Staying true to the early subversive spirit of the Hulk as envisioned by its creators (Stan Lee and Jack Kirby) while also tuning the tale to current dangerous times, Lee presents a portrait of a man at war with himself and the world, both a Super Hero and a monster, a means of wish fulfillment and a nightmare.

Committed to bringing the Hulk to authentic life, director Lee and his effects teams logged countless hours to assure a creature true to the essence of Kirby’s powerful seminal artwork and Lee’s mythic stories. Designers and artists returned to the original Hulk character conceptions to honor the Marvel traditions and place the creature in a motion picture world — grounded in reality, dictated by time-honored practice and colored by comic book convention.

About The Film

The character of “The Hulk” first appeared in a series of six Marvel Comics in 1962 as the creation of writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby. Two years later, the creature was pitted opposite Giant-Man in #59 of Tales to Astonish, and in the next issue of the series, earned his own separate story in the comic book. By 1968, the Hulk had taken over the entire book, which was then re-named The Incredible Hulk; the series ran to issue #474, ending publication in 1999, and was quickly resurrected in a new series (first called The Hulk, changed back to The Incredible Hulk with issue #12), which continues current publication without signs of slowing. It seems in the world of heroes (Super, anti- and other), it’s hard to keep the big green man down.

The immense popularity of the creature also spawned a successful CBS television series (1977- 1982), which starred Bill Bixby as scientist Banner and bodybuilder Lou Ferrigno as the Hulk. Following cancellation of the series, fans’ enduring affection for the tale of hunted scientist and his angry alter ego urged network executives at NBC to bring back the Hulk to the television screen and ultimately, three more telefilms were created and aired in the late ‘80s. Hopes for a fourth installment were dashed when Bill Bixby passed away from cancer in 1993.

During his career as a Marvel Comics character, the Hulk underwent several changes (early on, the creature was gray, not green, and a nocturnal being). Throughout, however, he was always linked to his alter ego, scientist Bruce Banner, and the two were intertwined in a constant, uneasy relationship. It was this relationship that seemed to keep alive the fans’ enduring devotion to Banner/the Hulk and exactly this yin-yang dynamic that made the character ripe for a cinematic appearance.

Executive producer and co-creator of the Hulk character Stan Lee remembers, “When I was younger, I loved the movie Frankenstein, starring Boris Karloff as the monster, and I also loved Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. One day, I figured, ‘Boy, wouldn’t it be cool to combine the two of them and get a character who can change from a normal human into the monster?’ I always felt that in the movie Frankenstein, the monster was really a good guy. He didn’t want to hurt anybody—he was just always being chased by those idiots holding torches and running up and down the hills. So I thought, ‘Why not get a sympathetic monster, but let it be a guy who can change back and forth?’ So, the Hulk became the first Super Hero who was also a monster.”

Producer/screenwriter James Schamus, Ang Lee’s longtime filmmaking partner and collaborator, comments, “Unlike a lot of other Super Heroes, the Hulk is a Super Hero, a monster and a person, and the various Hulk comics include the drama between generations of families, the quest for his origins, how he came to be who he is, the mystery of who he is…all of those things.”

It was the character’s internal conflict and the dramatic dilemmas it posed that also attracted producer Gale Anne Hurd to the property.

“I always thought the story of the Hulk, as presented in the Marvel Comics, had elements of a Shakespearean tragedy that had great cinematic potential,” Hurd says. “There was real, elemental drama of the human condition in this character. What I always liked about the Hulk was that he was a hero, but not really a Super Hero, not when compared to the other Marvel crime-fighting characters. The Jekyll and Hyde conflict intrigued me. Part of it is a cautionary tale, not only about the demons that we have to come to terms with inside ourselves, but it is also a bit of a commentary about the ramifications of having the technology to create a Hulk. The comic book dealt with Cold War issues, but we’ve been able to update it and it’s relevant, if not more relevant, now.”

Hurd, whose many blockbuster credits include Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Aliens, The Abyss and Armageddon, understands the notion of using computer generated imagery (CGI) to further a film’s characters and plot. She points out that the wait to make the film was fortunate as it allowed technology to catch up to the special needs of the Hulk.

“The great news is that over the course of the 12 years this project has been in development, the technology caught up with our passion for the project. We now have the technology to create the Hulk the way it should always have been approached. Now, with CGI, with the techniques that have been developed at [leading visual effects house] Industrial Light & Magic, we are able to go beyond what could’ve been imagined on the television show or even on film. There might have been ways to put the Hulk onscreen before now, but it wouldn’t have been The Hulk imagined by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby,” the producer comments.

While the technology and interest in “comic book” movies may have auspiciously dovetailed, Marvel, as producer and Marvel Studios CEO Avi Arad points out, is very sensitive and selective when it comes to allocating its characters and their worlds to filmmakers. “At Marvel, we view our comic books and characters as our children and we have to find them the appropriate surrogate parents, filmmakers who will bring something special to the project. Whenever you hear the word ‘comic book,’ some people see a fist with the word ‘POW’ on it. What they are really about are characters, very interesting people who have gifts and curses and complicated lives. Our movies must be made by real filmmakers and real actors because it takes tremendous range to play and deliver these roles,” Arad notes.

Producer Hurd, whose ability to assemble extraordinary ensembles of filmmaking and acting talent to create just that sort of dynamic, understood the keen sense of balance that would be a requisite of the project’s director.

She notes, “We always had Ang Lee on our list of potential directors. So when Universal suggested it, Avi and I felt that Ang would consider it because there is no more complex character than Banner/the Hulk. It’s the ultimate split personality—two individuals that need to live with each other one way or another. They are tied in genetically, but they want to destroy each other and themselves at the same time. Looking at Ang’s movies, I felt his keen interest in the inner soul, his sense of humor, his interest in family dynamics, in the relationships of fathers and sons, his inventive action in Crouching Tiger…he had all the ingredients to make a great movie.”

“We always thought that Ang was an incredibly interesting filmmaker because he never repeats himself,” Arad adds. “He moves seamlessly among the different genres and there are very few directors who can handle anything. Because our character Bruce Banner and his alter ego the Hulk are deeply rooted in rich drama, you really want someone who is an actor’s director. With Crouching Tiger, you saw that he could deliver something that was rich and epic in scale, but at the core, what really made that movie successful was that you cared about the characters.”

James Schamus concurs with Arad, noting that the tale of the Hulk plays to Lee’s interests and strengths. He adds, “We moved the script in directions that would allow Ang a chance to grapple with certain ideas—the familial conflicts, the search for Banner’s past, the genesis of the Hulk. More importantly, I think that Ang also sees the emotional, positive side of the Hulk. He understands that the Hulk isn’t simply a monster that is there to scare us, but that everyone has the Hulk in them and there is something very enjoyable, very empowering about experiencing hulkness. So, he was very interested in, for want of a better term, the entertainment side of the Hulk. He wanted to make it a very pleasurable experience, too.”

The director himself says, “I had just finished Crouching Tiger when the studio approached me about The Hulk. It seemed like an interesting extension of my work … I called it my new Green Destiny [referring to the fabled sword in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon]. The early Hulk comics were especially inspiring for me—the energy and dynamics of Jack Kirby’s drawings, the dramatic freedom of the stories Stan Lee created. They dealt with huge issues and fears, and finding within those fears the will and imagination to understand them. I feel that everyone has a Hulk inside and each of our Hulks is both scary and, potentially, pleasurable. That’s the scariest thing about them.”

Lee adds that The Hulk also offered the opportunity to delve into a variety of potentially opposing themes and topics, and the challenge of balancing and connecting them attracted him as well.

He continues, “We addressed this question a bit in Crouching Tiger—how do you take a popular genre, like the martial arts film, and approach it with intelligence, without making it too cheesy but still fulfilling the demands of entertainment? We had similar challenges with The Hulk, but that is what is exhilarating about it. I think it’s possible to treat this mixture in a very emotional way as well. The Hulk, like Crouching Tiger, is a weird combination of pop culture and realistic drama. I think by nature, these two aspects don’t want to get along but I try to mix them. How much should be realistic? If it’s too realistic, how can you believe in a green giant or that people can fly? How to combine something that is visually exciting, very free, almost like a childhood fantasy, with the reality of psychodrama, comedy, romance? These are contradictory elements, but to me, they represent the dilemma of my own life in filmmaking. The toughest thing for a filmmaker is to keep it balanced. It’s like walking a constant tightrope and that’s a thrill for me.”

The most successful of formulas often arise out of the unexpected spark produced by an unlikely combination of elements—just ask Bruce Banner—and when it came to casting The Hulk, filmmakers were able to assemble an outstanding roster of actors which, when combined, would render the film a true ensemble event.

The cinematic balancing act that characterizes Lee’s approach to his work and to The Hulk began, quite naturally, with the film’s divided main character. Although the wizards at ILM would ultimately give life to the “green Goliath,” the filmmakers knew it was crucial to cast an actor who could inhabit his human incarnation, conveying not only his inner conflict and repression but, ultimately, his compassion.

Australian actor Eric Bana, a comparative newcomer, won the part, primarily on the basis of his first movie, a disturbing tale of a charming killer called Chopper. “Eric played a kind of human monster in Chopper, someone who was so monstrous because he was so human, too,” Ang Lee observes. “With just a simple look, he could communicate a kind of superhuman fury and intelligence. I thought it would be marvelous to see him as Bruce Banner, having to suppress that energy until he couldn’t take it anymore.”

Bana says that Banner’s turmoil intrigued him, but there was a key reason for accepting the role. The actor offers, “The most obvious hook was the fact that Ang Lee was directing it. The thing that attracted me to the character of the Hulk in particular was the fact that he is a slightly reluctant hero. And the Hulk can’t control being the Hulk, really—Batman goes into a cave, Superman goes into a phone booth—but it just comes over the Hulk, which attracted me as an actor.”

Part of the challenge for Bana was to channel not just the character’s emotional nuances but also Lee’s prismatic and sometimes fragmented vision of Banner and his world. “I knew that whatever Ang tried would be entirely unique and unpredictable. It also turned out to be very difficult to prepare for because the character undergoes so much soul-searching. It was hard to get a specific handle on what exactly I needed to do or research, but I tried to use that, because, in a way, that uncertainty is part of Bruce Banner’s dilemma. Ultimately, it was about trusting Ang and his vision. I just went in with my eyes wide open. When I first read the script, I was blown away by it. It was very layered and complex but I also knew that there was a lot that was in Ang’s head that wouldn’t necessarily translate to the page. I knew that whatever he added would be incredible and probably way beyond my wildest imagination, and that turned out to be so,” adds Bana.

Because the Hulk would be a completely computer generated being, Bana never had to endure the rigors of turning large and green; his performance, however, had to pave the way for the emerging CGI Hulk. The artists at ILM were occasionally consulted by the actor for help in fomenting postures or specific facial looks that would become the starting point for the human-to- Hulk transformation.

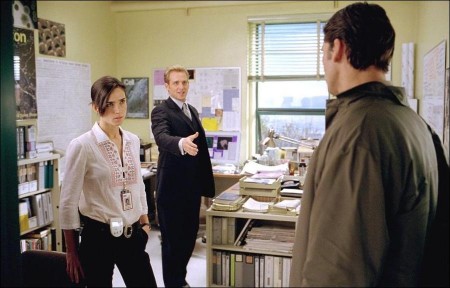

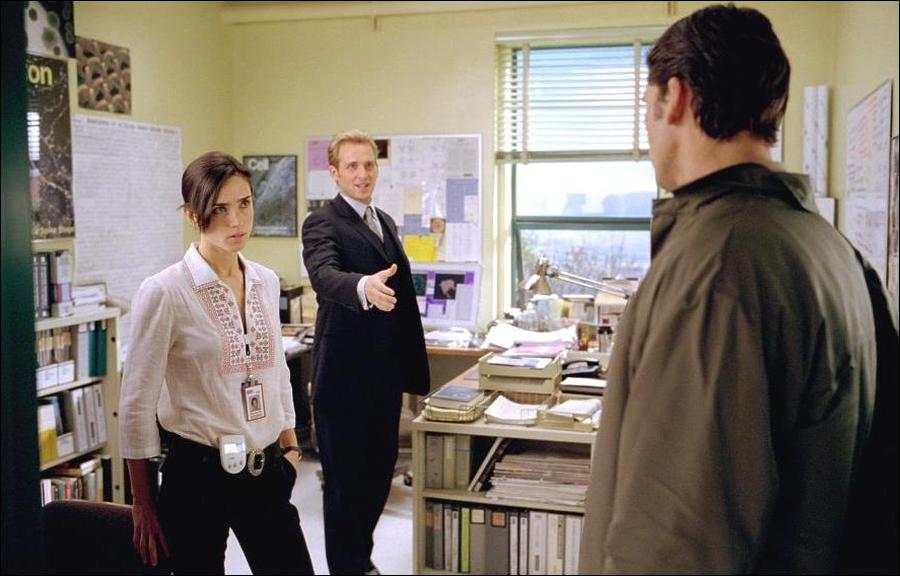

“It was a lot to store in my head, but it was fun at the same time. It required a specific level of concentration and it was helpful to know that I didn’t have to take it the whole way. I wasn’t inhibited by having to stop and get into make-up or some green suit. Also, it allowed me to absolutely go for it, based purely on the ideas that Ang had put into my head, and to just get really emotionally and physically ugly,” Bana muses. Jennifer Connelly earned the role of Betty Ross, Bruce’s colleague, friend and former girlfriend who comes to be the only humane link between Banner and the Hulk. Like the original Marvel Hulk, Betty Ross changed over the course of the comic book, but her essential love and sympathy for Banner remained throughout the series and infused the character in Lee’s film.

Early during production of The Hulk, Connelly won the Oscar. for Best Actress for her portrayal of Alicia Nash in A Beautiful Mind, but it was another film that brought her to Lee’s attention.

The director remembers, “I saw Jennifer over the years in many films, but her performance in Requiem for a Dream touched me so deeply for its tragedy and intelligence. She stood out as the perfect choice for Betty.”

Schamus adds that Requiem for a Dream, an unsettling film about the loss of self to addictions, clearly proved Connelly’s fearless ability to mine treacherous emotions, which was important to the role of Betty. Equally crucial, he notes, were her keen insight and intellect.

“Ang was not interested in casting the part of Betty as ‘The Chick Role,’ and the first step was to really find somebody who could credibly create the role of a character who is as smart as Banner, if not smarter, and is a scientist in her own right. Intelligence was the first requirement for the part. You don’t have to worry about that with Jennifer, who went to Yale and Stanford,” Schamus says.

Connelly remembers, “When I heard that Ang was directing the project, I was immediately intrigued. I thought, ‘Wow, what an interesting combination of elements.’ As a child of the 70s, I remember watching the television series. And then when I spoke with Ang, he really wanted to make this a psychological drama, to explore the relationships within the families—between Bruce and his father, and Betty Ross her father. What I thought was so interesting was the juxtaposition of these really human characters struggling to work out their relationships with one another against the sort of comic book, larger-than-life, ‘this guy goes green’ sort of elements.”

Yet putting aside all of the intelligence and strength inherent in the character of Betty Ross, for Connelly, part of the key to her character is, “…that you sense there’s something kind of vulnerable about her, something missing, something slightly broken about her. Her relationship with Bruce is complicated. They had a romantic relationship, which did not work out—but they are still professional partners. And Betty is still very much in love with Bruce.”

And it is that love that makes matters even more complicated when the ramifications of Banner’s heroic decision to place himself in the path of the gamma radiation blast become evident. Betty had been keenly aware of her partner’s stranglehold on his darker emotions, and she is the first to piece together the link between Bruce’s anger over past occurrences, his exposure to a combination of nanomeds (sub-molecular machines) and gamma radiation, and the resulting transformation into the Hulk.

She explains, “Betty recognizes, even before the accident, the effect that anger, or rather the suppression of anger, has on Bruce. And then she is the first one to sense and piece together what’s going on after the accident. She recognizes that in the Hulk. She recognizes Bruce and stands her ground. Others respond with an escalation of violence, but Betty stands there in front of him and looks at him as if to say, ‘I’m here, I understand, I love you and I see you…and it’s going to be okay.’”

Acting with Connelly, Bana had almost a mirror experience to the Hulk/Betty face-off. “With Jennifer, I always knew we’d get to the heart of the scene,” adds Bana. “I knew straight away that I’d be playing opposite an incredibly gifted actor. You can’t really ask for anything more than that.”

As scientist David Banner, Bruce’s father, his early inspiration and a later adversary, filmmakers had a short list of actors—very short. “It was always Nick Nolte, our first and only choice,” says James Schamus. “It was a no-brainer.”

“Nick is an actor’s actor,” Ang Lee comments. “He is generous and fearless with everyone and is a great spirit. He immediately saw connections in the film between popular Western culture and Eastern philosophy that I didn’t even see.”

The actor explains, “I had seen Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which I liked very much, and later watched The Ice Storm and Eat Drink Man Woman. I was curious about Ang and The Hulk—the combination of Ang and the source material interested me. I wondered, ‘Well, what is he going to do here?’ You have this comic book level, but then you have mythic proportions to it; you have psychological fantasies involved; you have childhood psychology, archetypal, primal stuff, smothered by a veneer of adult, pseudo-responsibility, false maturity, false wisdom and the gamesmanship of rivals. There was so much to it. And Ang seemed like a great choice because we get a marriage of the East and the West. That was exciting to me.” Nolte was also intrigued by the casting of Bana as his son.

He continues, “They told me they’d cast this Australian guy named Eric Bana as Bruce and they told me to go have a look at this film called Chopper. So, I did and I was horrified, absolutely astounded at the nature of this character he’s playing. It was an amazing transformation, he was just tremendous in that piece. I looked forward to working with him and I wasn’t disappointed.”

Nolte adds that from the start, he and Lee were in sync in terms of the character and the various underlying themes The Hulk presented. The two enjoyed an ongoing dialogue about “…the father/son relationship, the integration of the shadow side of our personality into the light of day, the constant play between what we would consider our conscious good side and our unconscious dark side, the good and bad, the right and wrong, the up and down.”

All of this work, and the wealth of Nolte’s talent and experience, made him ideal to play Bruce’s father, David, an intense scientist whose pioneering work in genetics pushes up against the boundaries of ethics. His single-minded passion as much as his research and experiments forever alter his and his son’s lives and inexorably link their destinies. While some may see him as Banner’s foe, Nolte insists his character is motivated by his love for Bruce, although it manifests in an unconventional, even twisted manner.

There is no love of any kind between Glenn Talbot (the adversarial character also taken from the Marvel series, played by Josh Lucas) and Bruce Banner. For all their similarities—an interest in science, a sharp intelligence, not to mention an underlying affection and rivalry for Betty Ross— the two diverge in terms of the application of their knowledge and power.

Josh Lucas observes, “Talbot is incredibly driven, extremely ambitious, powerful, probably extraordinarily self-righteous and ruthless. He is a military trained, disciplined human being who truly believes that he is exalted and that his ideas are going to transform the world and, therefore, he has a right and a duty to achieve them by any means necessary. He is the type who believes that his political and sociological ideologies are so correct that they will do anything to fulfill their own prophecy.”

Lucas adds that playing someone as grandiose and self-centered as Talbot was exceptionally enjoyable. “He is so crazily free, so maniacal, unafraid and dominating that there is this great comic book element to him. I’m not a particularly antagonistic person, but everyone has some hostility or aggression inside, which is one of the points of The Hulk. I don’t get to release those elements of my personality on a daily basis and often, as an actor, it’s easier to play characters that are further away from your normal life. It was almost playful to portray him and absolutely fun. He’s also a terrific foil for Banner, who is so obviously suppressed.”

In fact, Talbot finds the key that unlocks Banner’s assiduously bolted rage and primal fears and the two adversaries come to blows. While Bruce Banner may not be much of a fighter, his alter ego has more of a temper and the will and physicality to exploit it.

“I got my ass beat consistently,” Lucas happily sums up. “Because of Talbot’s military background, he has great physical presence and balance. All that is fine when Bruce Banner is a human being, but when he transforms into the Hulk, Talbot is out of his league, even though he refuses to accept that. So, I spent quite a bit of the film being tossed around the set.”

Lucas’ delight if not downright glee in playing Talbot was not lost on his director. Neither were his additional talents. “Josh displayed so much enthusiasm and sheer fun in shooting the film it was hard for me to believe that he is also one of the most controlled and gifted actors I’ve ever worked with—a real perfectionist after my own heart,” Lee muses.

Of course, the Hulk, not Bruce Banner, pounded Talbot, but the brawls began between the alltoo- human Bruce and Talbot. Talbot initially trounces his opponent, who has so much invested in quashing his animosity and aggression for fear of what they might unleash…the Hulk. In other words, Josh Lucas spent weeks pummeling Eric Bana.

“It’s my aim in life to do a boxing film with Josh Lucas to try to get some revenge,” Bana jokes. “Unfortunately, only the Hulk gets that satisfaction in the film. As Bruce Banner, I never really get to wrap his arms around Josh Lucas and slam him up against the wall. But it was fun.”

The link to Banner, Betty, Talbot and David is General “Thunderbolt” Ross, played by the accomplished Sam Elliott. The beloved and award-winning actor brings with him his own brand of quiet authority and weighty personae, made all the more forceful by his lengthy resume of genre-defining roles in Westerns, political thrillers and action movies.

“Sam just had a bearing that I was searching for,” Lee explains. “A military man who is also, at heart, a father.”

“I think the most important and perhaps most troubled and confounding relationship for Ross is the one between him and his daughter Betty—even though he is the connective tissue between all the characters, because he has been involved with all of their lives on some level for many years,” Elliott says. “On some level, it is a typical/father daughter relationship, in that it’s not all roses and it’s a bit tenuous. Ross is a successful, career military man but, because of his duty to his work, he has failed on a lot of levels with his daughter.”

The journey Ross takes to uncover the mystery of the Hulk also leads him to an uneasy rapprochement with his daughter and inadvertently causes him to examine his own buried emotional issues.

“I don’t think that on a scientific level Ross has a clue what has gone on to lead to the Hulk. He knows enough of the history and sees the potential threat to his daughter to realize that it is something he must try to control. Therein lies the problem – as a military man, his instinct is to contain what he perceives to be a menace, as he has tried to do for years, which, of course, is impossible. There are a lot of sources of frustration for Ross and he is unaccustomed to that predicament, those feelings,” observes Elliott.

A Being, Green

While understood that the Hulk half of Banner would be a creation of advanced moviemaking technology (i.e. computer generated imagery), the young actor playing his other half was to be the starting point for the creature. Banner’s mannerisms had to be discernable in the creature—if to no one other than Betty Ross—and Bana himself would need to exhibit specific body articulations in certain scenes as Banner on his way to “hulking out.”

Groundwork began on this in sessions organized by stunt coordinator Charlie Croughwell during pre-production; these workouts not only prepared Bana physically, but mentally and emotionally as well. Croughwell dubbed his sessions with Bana “Hulk School” and the actor attended as often as he could, even well into the beginning of principal photography. Since the director wanted the Hulk to be agile as well as strong, a variety of training techniques were utilized to build on the actor’s strengths and finesse the movements from athletic to almost choreographic— all of this intended to give an origin to the monster’s movements, as what Banner does feeds into the Hulk’s physicality.

“I’d never worked on a film with CGI before and this was obviously special because of ILM and Dennis Muren and his team,” says Eric Bana. “It was like working on two different films at once, which made it very interesting and exciting. We’d do this intense scene and I’d feel like I was in the most dramatic film and then I’d have a couple days off and come back and wonder, ‘What is going on here? What happened to the dark, personal drama I was working on? They’re ripping down walls and destroying sets.’ It was fascinating.”

Bana’s performance became the template for the Hulk’s emotions and reactions, but ultimately, it wasn’t possible for Bana to approximate the Hulk’s gargantuan movements and colossal destruction.

“Although there are human elements to the Hulk, he can’t move like a person because he is so immense and because, ultimately, he is a monster,” says ILM’s nine-time Oscar. winner, visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren. “It was much more appropriate and truer to the character to create that in the computer.”

It was an accepted fact that literally the largest of the film’s stars would never appear on the set, despite his having to perform opposite every other cast member in the film. So, it was up to the production team and the wizards at ILM to come up with alternatives to represent the creature.

So, enter the “stand-ins” for the Hulk. The most basic was a crude rendering of the Hulk’s head on a telescoping pole, which became known as “Elvis.” Additionally, ILM introduced a series of other objects and instruments to provide such information as how the creature should appear in the frame and how the light reflected and refracted off of his enormous shape—these became known as the “Reference Parade,” which were comprised of a large green Hulk bust, a sphere with both a shiny and a matte surface and a large oval emerald piece of Hulk “skin.” (When these objects were needed in a shot, the first assistant director would call out to “bring on the Vannas,” and the visual effects coordinator, an ILM representative and a stand-in or production assistant would display the objects at various angles for the camera and benefit of ILM.)

Director Lee explains, “I loved the old Hulk television show and it was a thrill to have Lou Ferrigno come and be a small part of our film. Back when the show was being made, a bodybuilder was the perfect solution. But, my Hulk has to be more than an embodiment of human strength. That is why this film could not be made without the help of the geniuses at ILM. We have approached the Hulk design from both the inside—with all the amazing ways they can create bone and muscle structure in the computer and then make it move—and also from the outside, taking inspirations from everything from Tibetan masks to the emotions we record on the face of his real-life co-stars. The Hulk has to perform opposite award-winning, amazingly gifted and subtle actors. The key to the Hulk will be how good an actor he is. Our hope is that through computer animation, we can approach something that is haunting and emotional and not just a gimmick of computer work.”

Honing the Hulk’s computer generated movements (that wished for combination of agility and massive strength) proved to be an ongoing, organic process. Fortunately, Dennis Muren and his ILM team have extraordinary wellsprings of ingenuity and imagination.

“From the beginning, we wanted Dennis Muren on this movie,” says Gale Anne Hurd, who had worked with him on Terminator 2: Judgment Day and The Abyss. “From the first time that Dennis and Ang met, there was magic. There was an immediate meeting of the minds, not just to use the technology merely to create something cool, but to create a character in the Hulk who could act.”

This meant, among other things, that occasionally Muren and company eschewed traditional techniques. For instance, ILM preferred to minimize the standard use of motion-capture, whereby a computer “captures” human movements in a painstaking system that involves attaching electrodes to a person wrapped in a special suit.

Animation supervisor Colin Brady reasons, “Motion-capture has its benefits, but we didn’t want to start with it because although it gives the computer a sense of the way a body moves in space, it still can be a bit restricting. People tend to freeze up when they do it. It’s always awkward to be in that suit with these electrodes stuck to you with a bunch of people around watching. With all of that, you’re left with a limited amount of movement. Besides, ultimately, why would we want to be limited to just what a human can do? It’s the Hulk.”

Brady adds that while they wanted the Hulk’s moves to be colossal and brutal, his gait and action still had to obey the laws of physics, albeit in an oversized way. So, they began their research by digitally taping specific people engaged in a bit of Hulk therapy, beginning with a stunt man smashing up a room filled with styrofoam objects. ILM recorded this fury and further manipulated and exaggerated it in the computer. And others followed.

“We tried using body builders but found they weren’t agile enough” Brady says. “Ang didn’t want the Hulk to be too lumbering or muscle-bound. We ended up studying a personal trainer/triathlete, who stopped by every so often and smashed up a bunch of boxes for us.”

Once the ILM artists (and their complex array of computers) had a basic vernacular of the Hulk’s movements, more refinement was completed utilizing the motion-capture technique. While several athletes and stunt performers donned the specialized equipment, Lee himself enacted a number of the Hulk’s scenes in the cumbersome suit; adding an almost Frankenstein twist to the filmmaking process, it was primarily the director’s movements that ultimately provided the basis for the creature’s on-screen life.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing ILM was that the Hulk is born of complex emotions and, as Lee pointed out, not only has to convey his feelings but do so opposite some high caliber acting talents. The task was formidable, made more so by the close proximity between the actors and the Hulk.

Muren elaborates, “Unlike, say, Jurassic Park, where the actors and the dinosaurs shared screen time but didn’t interact much on a one-to-one basis, the Hulk has to appear and act opposite the main characters. That dictates a great deal more complicated work.”

Given that the Hulk had more “realistic” scenes and physical contact with the other actors, ILM labored to craft subtle facial movements and to refine the skin texture alongside the developing motor movements.

The cast and crew saw pieces of the nascent Hulk from time to time when Colin Brady appeared with his laptop computer. Within were several “animatics,” rough animation of the Hulk “acting” in the scenes, complete with all the camera angles. This benefited Lee, the actors and the technicians responsible for the physical effects of a scene involving the Hulk, who could get a rudimentary sense of the final scene in Brady’s computer.

During production, however, the only Hulk anyone saw was the ubiquitous Elvis, propped up to give the actors, the camera crew and ILM an eye-line.

Paramount to all—everyone from director Lee and the producers to Brady, Muren and the ILM crew—was the creation of an authentic Hulk, respectful of the rich Marvel heritage and the definitive artwork of the creature’s original Dr. Frankenstein, illustrator Jack Kirby.

Producer Avi Arad notes, “‘Obsessive’ might be a good word to describe our efforts to give birth to a Hulk within the perimeters laid out by Kirby, Lee and Marvel, yet providing a natural progression from comic book page to movie screen. It’s all right there in the source material — his size, his strength, his ability to accomplish superhuman tasks, like bounding great distances in one leap. We didn’t come to this project and say, ‘All right, now that the Hulk is in a film, let’s enlarge his scale, his capabilities, let’s change this, let’s change that.’ We were handed an amazing creation with a rich mythology that didn’t need any aggrandizing on our part. It all came from a place of respect to the lore.”

Producer Larry Franco adds, “While the Hulk was being created and then refined at ILM, Ang Lee literally moved to the offices in Northern California to personally direct the creature. Building on the earlier limited motion-capture work, he spent months with the artists to refine its facial movements, expanding the creature’s muscle articulation capacity and enlarging the scale of available emotions that it could express.”

Dennis Muren summarizes, “In the end, the countless ILM man-hours gave birth to a creature that can lift 5,000 pounds, jump three miles at a time, run 100 miles-per-hour and that grows from nine feet to 12 feet, then to 15 feet tall. This amazing being has a physique that would make classic strong men appear anorexic. Today’s sophisticated audiences would not accept this from a human actor in green make-up, even augmented with robotics.”

The meticulous work from the wizards at ILM, the majority of which was the most complex the designers had ever executed, included:

— Painting and developing 100 layers of skin (the layers representing everything from skin color to veins, wrinkles, wounds, dirt, wetness, blemishes, hair) utilized in groups of 10 or more. All of the layers combined to render the Hulk as human and blend him seamlessly into each scene.

— Creating 1,165 muscle shapes for the Hulk’s entire range of movement.

— Logging 2.5 million computer hours and six terrabytes of data over the one-and-one half year journey it took to bring the Hulk and other characters to life.

— Utilizing 69 technical artists, 41 animators, 35 compositors, 10 muscle animators, nine CG modelers, eight supervisors, six skin painters, five motion capture wranglers and three art directors.

While the work continued on creating the Hulk himself, the shooting crew had to provide ILM with the devastating physical effects of the Hulk’s wrath. This meant, for instance, when the Hulk beats up Glenn Talbot or when he encounters Betty Ross face-to-face, Josh Lucas and Jennifer Connelly became defacto stunt people. In Lucas’ case, this meant about a week of phantom pummeling and flying through the air on wires while filming at night at a Berkeley Hills street specially built on the Universal backlot.

“It was actually very interesting and fun,” Lucas says. “We spent a number of days playing with the balletics of a wire spinning me through air and tried to find a way to make it look both as raw and as natural as possible. We didn’t want it to appear like someone on a wire—Talbot is wildly out of control as the Hulk picks him up repeatedly and flings him.”

Jennifer Connelly had her own experiences during filming her scenes with the Hulk, which involved a great deal of physical as well as mental work.

She relates, “During the first scene I have with the Hulk, he comes out from the trees and stands before me. Then he leans down and looks at me. So, we have to establish eye-lines, where he is and where he moves and, since he’s a digital creation, there is nothing there during filming.”

Nothing, of course, except the stand-in Elvis. While of a less violent nature than the Hulk’s scenes with Talbot, Betty Ross experiences the creature’s strength in one particular meeting. To continue with the director’s quest for authentic artistic moment, stunt coordinator Croughwell used the actors (whenever safe and possible) instead of his team or in lieu of the CGI bait-and-switch technique of attaching famous heads to stunt people’s bodies. This meant that, like Josh Lucas, Jennifer Connelly spent some time in the air.

The sequence took place in the Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest (which lies within the Sequoia National Forest), a breathtaking, primal spot studded with streams and lakes and the imposing, inspiring trees. The Hulk was the first production to film there and aside from the locale’s natural beauty, the trees provided obvious markers by which to gauge the Hulk’s immense size. At this picturesque place, the Hulk lifts Betty Ross. This required Croughwell to create an ingenious contraption.

“We figured it would be similar to a puppet on strings, like a marionette, except the puppet we manipulated was a human body, Jennifer Connelly, on a wire. We had her flying from an overhead rig and I had lines in my fingers. I controlled her rotation and her bounce with those lines, almost like a set of reins, which were manned by five crew members. We tested the rig with a double on stage so by the time we got Jennifer there, I knew what the movement should be and only had to fine-tune it a bit on the day,” the stunt coordinator explains.

Croughwell practiced with Connelly on the stage before shooting the scene in the forest and Connelly adeptly nailed working in the sling inside of 45 minutes.

The coordinator and his stunt team also worked with the Hulk, or at least with the destruction the Hulk leaves in his wake. This meant that Croughwell constantly coordinated with special effects supervisor Michael Lantieri.

“We worked very closely with Charlie and his guys, because many times, the stunt team had to provide the reactions to what the Hulk was doing. For instance, when the Hulk escapes from an underground tunnel, he doesn’t just walk through it, he bursts out of it and all the guards patrolling it get knocked around and fall off the platform. For any of the situations with the Hulk, Charlie and I meticulously talked about where someone could be, how to design an explosion that would appear as though the Hulk has created it by his sheer force. Safety was always the first priority and the performance was next,” Lantieri says.

The overall mandate, Lantieri adds, was to devise a scenario that seemed as realistic as possible, given that this reality revolved around an enormous green being with anger management issues. So, when the Hulk upends a trolley in San Francisco, Lantieri had to figure out how to topple an actual streetcar (filled with stunt performers) that the city had graciously provided. Typically, the Hulk, at some point, smashed up all the sets, which could not necessarily be made of flimsy, tearapart substances.

“Whatever the Hulk came in contact with, pushed, shoved, broke, touched or lifted was the responsibility of the physical effects crew. Ang wanted everything to be grounded in realism, so we couldn’t use breakaway materials because they were too light and didn’t convey the sense that something as huge and as formidable as the Hulk was there. So, when the Hulk goes on a rampage through the lab and throws a freezer against a wall and basically smashes up the place, it was all real glass or plexiglass, wood and brick,” notes Lantieri.

This technique added another layer of challenge to an already complicated production. For one elaborate scene, Lantieri invented a giant water tank in which Eric Bana spent about two days as the imprisoned and submerged Bruce Banner; the sequence culminates when the Hulk, finally fed up, bursts through the container. Lantieri had to invent a rig so that Bana could breathe underwater and the camera crew could get the necessary shots—but the tank also had to explode, sending water cascading through the set. Lantieri’s team and the construction department also had to consider the physics of capturing and directing all of the water to protect the film crew and the electrical equipment. Finally, he had to work closely with Dennis Muren and ILM, as they would have to insert the furious Hulk and possibly some CGI water during postproduction.

In general, to impart the Hulk’s overwhelming obliteration of everything in his path, Lantieri devised elaborate mechanisms—essentially huge wire and pulley systems linking the objects of the Hulk’s destructive fury to an immense source of power, generally hidden behind or below the sets, which could destroy or rip down on cue. Unfortunately, these types of shots could only be filmed once and Lee set up multiple cameras to capture every angle. For the scene where the creature crashes through a laboratory and tosses a freezer through a wall, Lantieri fastened a labyrinth of steel cables to hydraulic cylinders that exerted 800 pounds of pressure and 240 pounds of pull. Rigging the equipment and positioning seven cameras took about four hours and the shot was over in less than a minute. Needless to say, so was the set.

The Hulk takes place in San Francisco and the company filmed in the city for about three weeks. While there, the production made good use of Treasure Island, the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and the surrounding Berkeley campus, an industrial Oakland neighborhood and Telegraph Hill (the famed upscale neighborhood of Victorian houses near Coit Tower with a spectacular view of the Bay and a nearly vertical ascent).

In one scene called for in the script, the Hulk makes his way up the steep hillside. To create the disastrous aftermath of such a climb, the production filmed several scenes of chaos for a week: a trolley tipping off of its tracks; a line of cars jumping and flipping and nearly crashing; 400 extras, 35 stunt people (performing as passersby), S.W.A.T. teams and military personnel, all choreographed to respond to the Hulk’s passage from the Bay to the hilltop.

The apex of the week’s work was a procession of helicopters that proceeded up the hill in pursuit of the Hulk, hovering at the top before their final ascent. This exercise required considerable planning and community outreach because the filmmakers received permission to fly the choppers 75 feet above the ground, considerably lower than the F.A.A. approved height of 500 feet. To do this, the filmmakers had to evacuate the residents.

“The truth is that it’s just the law. We couldn’t fly a helicopter that low with civilians below us,” says producer Larry Franco. “We did everything we could to accommodate the neighbors—we compensated those whose roofs we used, we donated to local charities. We had the top helicopter pilots in the business. It was a legal necessity and precaution to evacuate the neighborhood and ultimately, the shots were successful and safe. The rest of it was just movie stunt work—the ground breaking, cars careening down the hill, stuff like that.”

Because the chopper sequence ultimately happened on a Friday when most people were at work, only a handful of inhabitants made their way to the local Chinese restaurant that the production bought out for the “evacuees.” The remainder took photos and videos of the choppers from the base of the hill. As for the production, four cameras on the ground and one airborne Spacecam captured the action.

“San Francisco is a beautiful city with many layers and I always wanted to make a movie there, it’s been one of my dreams,” Ang Lee says. “It is amazingly cinematic and romantic and I hope we honored it.”

While Telegraph Hill was not new to moviemaking, The Hulk did break new ground at Berkeley, becoming the first production to film the renowned Advanced Light Source (ALS)—a sprawling, Byzantine contraption that generates intense light for scientific and technological research that is situated near the Lab’s equally famous cyclotron. In a fitting bit of “movie reality,” its grounds were also the spot where the Hulk tosses the gammasphere onto a police car, although, as with all scenes involving the huge creature, the scientists, ALS workers, cast and crew only saw the Hulk-less results…the unfortunate crushed vehicle following its encounter with an enormous weight dropped from above.

Comic Origins

In the beginning, there was the comic book—the launching pad for the Hulk—and filmmakers treated the character’s origins as the Bible for all of the film’s story, physical production and design decisions. The Marvel Comics style infused all aspects of The Hulk and influenced every choice—everything from lighting, camera angles, framing and transitional techniques to color choices, sound design and costuming.

Like special effects supervisor Lantieri, production designer Rick Heinrichs tried to create a realistic environment, but his arena also allowed for degrees of fantasy and the influence of the comic book source material. This balance between reality and fantasy is familiar terrain for Heinrichs, who has collaborated with filmmaker Tim Burton on a majority of his films.

“I liked his work and I think he is an artist,” Ang Lee says. “Most of all, I think for a movie like this, it was important for the production designer to have visual training and an animation background, which Rick has. He completely understood the sensibility of what we were trying to achieve.”

“One of the things that interested me about Ang’s work was his take on the Hulk. Ang seems to be a student of Western civilization. The way he interpreted that, visually, was fascinating. He wanted to investigate these iconic images of America because, for Ang, I think there was something very Western, very American about the Hulk—men and their repressed anger and all that. Also, he wasn’t interested in going specifically in one direction or another—finding some equilibrium between apparent opposites attracted him. So, that was what we explored and it was quite a journey,” says Heinrichs.

Of course, Heinrichs studied the Stan Lee/Jack Kirby comics, but this creative journey led him and Lee to a variety of other artists—from late 19th and early 20th Century American painters absorbing Impressionist and Oriental styles and colors, to the later Surrealist De Chirico, whose colors and illogical, dreamlike subjects attracted director and production designer. (What Heinrichs calls the De Chirico color palette appears predominantly in Bruce Banner’s neighborhood and home.)

Heinrichs notes, “De Chirico was a painter who mainly worked in Europe but there is a very Southwestern feel to his color palette—rusts, burgundies, yellows. There are some very strong hues and mellow ones mixed together and if you drive around the Berkeley Hills, you see this eclectic mix of colors. On our early scouts there, Ang would point out, ‘Hey, there’s a De Chirico.’”

Heinrichs favored another color combination—one used not only by Kirby, but by some of the earlier comic book illustrators. “We also looked to the comic book artists of the early period. We borrowed conceits begun by early illustrators in both their color selections and their concepts. For instance, typically, you’ll see a lit sky with a darker landscape, but if you study the works of artist/illustrator George Herriman, he would frequently switch that to a black sky with a lit landscape. We used that idea in a scene in the bathroom. We had a very dark color up above but a very light green tile below. There was something about that exchange I just loved. It turns you on your head a little bit and it’s part of that duality thing, that tension between the light and the dark, between the simple and complex, the expected and the unexpected,” he says.

Heinrichs admits that the Hulk’s signature colors also make appearances but, he hopes, not in an obvious way. Greens and purples were used as a nod to the comic book, and as a theme that follows Bruce Banner through his life. Also, the designer followed the director’s dictate for reality, but with a certain amount of leeway, specifically with regard to the subterranean government base where the captured Hulk is taken.

Given the secret nature of such bases, not a great deal of information was available, although Heinrichs did study some photos of NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command, the U.S./Canadian multi-base organization charged with deterring, detecting and defending North America against air and space threats). Rick treated these photos as a springboard for his imaginative design of rabbit warren-like, interconnected series of hallways, claustrophobic tunnels and dehumanizing labs and offices. Heinrichs used bright colors in this set—yellows, greens, oranges and reds—and against the industrial grays of the tunnels, the appearance was, well, almost comic book.

“The truth is the government uses those colors in buildings. They all mean something. We just pushed them a little bit,” Heinrichs says.

Science and the natural forms at the core of its research also influenced costume designer Marit Allen’s work. Allen, who edited British Vogue during one of England’s most expressive and revolutionary fashion eras—from the early 1960s to the early 1970s—knew a thing or two about combining apparently antithetical elements in original and seamless ways.

“Ang wanted the scientists to appear as realistically as possible. In order for the fantasy to work, it had to be rooted in truth. Our first order was ‘no lab coats.’ Because Bruce Banner’s research involved genetics and because, of course, his affliction is bound up in his genes, Ang was also very interested in living things. So, that influenced our colors and textures,” Allen says.

Jennifer Connelly’s wardrobe, Allen says, particularly mirrored the natural elements but also conveyed Betty Ross’ personality and interests. Her wardrobe reflected her femininity, her physicality and her practical nature and was comprised of traditional American pieces, with influences of a bohemian, San Francisco style.

Of course, Bana had to wear the trademark purple pants/shorts at some point. This garb proved to be tricky, because Allen had to compensate for the Hulk’s huge growth spurt. Logically, she says, the Banner/Hulk transformation would rip puny human clothing to shreds. Indeed at a certain point in the film, the Hulk stomps about completely naked and Banner is likewise exposed in his post-Hulk position. However, Allen decided the violet pants would be a jersey material that stretched, to some extent, and tore as the Hulk expanded, but didn’t disintegrate.

Bana, Allen says, provided a particular challenge because, “he is such a perfect specimen that we had to hide his body, in order to express the idea that he is a scientist who spends much of his time at a computer or in a lab. We tried to avoid clothes that clung to him and we tended towards darker colors, especially blues. His wardrobe was very basic in cut and fabric—he is the ‘Everyman’ of the movie. However, a lot of work went into his costumes—we did a huge amount of dying and processing of these tones to compensate for the lighting and for everything happening on set,” Allen says.

Weird Science

It is one thing to try and ground a film in reality when dealing with such issues as physical movement, set construction, costume creation—even an enormous CG monster that leaves a wake of destruction. There is room for a certain amount of subjectivity (“Would the Hulk move that way? Would the military base look like that? Would Betty wear something similar to that?”). But when science is to figure heavily in a film, providing the environment in which the story unfolds? It is advisable to have, well, a scientific advisor…enter John Underkoffler.

Science consultant Underkoffler helped to guide Lee, the cast and the crew through the intricate vagaries of the science that might create a Hulk and, in the process, the director learned to appreciate the pure artistry of the miniscule forms that might lead to such an immense monster. Underkoffler primarily made sure that the story was rooted in accurate science and that the jargon was at least based in reality.

Underkoffler relates, “The first thing they wanted me to come up with was an explanation for the research that the scientists in the film were pursuing, which would then lead to the accident that creates the Hulk. Lee also wanted all the background, the techniques and gestures—from how to hold a beaker to the more theoretical—to be as realistic as possible. Audiences are increasingly savvy about this stuff even if the general audience may not have much familiarity with this argot, it recognizes when the rhythms are authentic.” In what can only be described as a reversal on the “art imitating life” maxim, TIME’s February 17, 2003 cover article, “Secret of Life: Cracking the DNA Code Has Changed How We Live,” included commentary and conjecture from a bank of leading scientists on gene research.

In it, journalist Nancy Gibbs points out, “Gene therapy allows doctors to introduce some handy gene into the body like a little rescue squad…” that can repair damage on a sub-cellular level—in essence, providing factual back-up for the science-fictional research being executed by Bruce Banner and his colleagues.

Gibbs goes on to say, “The nature-vs.-nurture debate changes when scientists find a gene that makes you shy, makes you reckless, makes you sad.”

Cracking the genetic code may have indeed unleashed a possibility for alterations to “life as we know it,” paving the way for, if not a Hulk, at least the reparation of genes—a topic that continues to be hotly debated within the scientific and ethical communities.

Another factor in the lore of the Hulk—gamma radiation—also recently made the pages of the April 29, 2003 edition of The New York Times. The article detailed the use of the Gamma Knife, a scalpel-less form of surgery that combats brain tumors by blasting them with “hundreds of high intensity radiation beams in a single session.” The form of radiosurgery, FDA approved in 1987, has received increased usage recently, accounting for “nearly 10 percent of brain operations in 1999.”

In such a world where the gap between science fiction and medical fact grows ever smaller, Underkoffler worked to impart a practical authenticity, giving the actors a crash course in science and accompanying Lee and the principal cast to Cal Tech in advance of principal photography. He also met with the actors and worked with them on the background for their characters, including their education, their career trajectory and their specific scientific discipline. While at Cal Tech, the actors received hands-on training with laboratory equipment and observed research scientists in their day-to-day routines.

Of course, the original Hulk tale has a specific bit of science built in, namely the gamma radiation that transforms Bruce Banner into the Hulk. Yet director Lee wanted something that went beyond the 1950s thoughts about radiation and the period notions about the effects of exposure.

James Schamus points out, “As in the original comic books, there is an accident—Bruce selflessly attempts to save somebody else and is hit with what would be, for anyone with a normal genetic makeup, a fatal dose of gamma radiation. The accident triggers something very specific in his cellular chemistry, which is the result of his father’s own self-mutating research. Passed down from his father, Bruce’s mutated DNA allows him to withstand the gammas and is, in fact, awakened by the radiation. When he is angered, his years of repressed emotions kick this juiced-up DNA into overdrive and the Hulk emerges.”

Filmmakers didn’t need to invent any scientific grounding for the catalyst that triggers Bruce’s transformation. Studies, articles and books have been written that document the investigation of the amazing effects of the addition of a simple dose of adrenaline into the bloodstream of animals and humans.

Case in point: A 1993 article in the bio-scientific magazine IPC announced the discovery of the molecular key to nature’s “fight or flight” response by U.S. scientists, who found the link between the release of stress hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream and the resulting quickening or slowing of the heartbeat…providing creatures the ability to remain and battle or run and seek refuge. Once the hormones are released, receptors called “adrenergic receptors” on smooth muscle cells—particularly in the heart and blood—trigger a chain reaction that either constricts or dilates arteries and slows down/speeds up heart rate; these momentary reactions have been known to provide episodes of what could be perceived as superhuman strength, providing the creature threatened a brief episode of “hulking out” (e.g. the 123-pound Florida mother who lifted a 3,000-pound vehicle off of her trapped child; a California seventhgrader, dragging his unconscious 185-pound father up a 100-foot ravine, lifting him into a truck and then driving him 15 miles to safety).

The culprit that administers Banner’s transforming radiation is a dome-like structure with colorful green, yellow and red pods dotting its circumference, known as the gammasphere. While the gammasphere’s functions in the film are fictional, the object is inspired by the only one in existence housed at the University of California at Berkeley.

“Ours was almost an exact visual duplicate of the real one at the Lawrence Berkeley lab, although it weighed a lot less,” Underkoffler says. “When Ang and Rick Heinrichs visited Berkeley, they saw this fantastic object that was designed for sensitive experiments involving nuclear interactions and decay that can record very detailed pictures of the gamma signature left by reactions. It happens to be an amazingly beautiful object that is very cinematic, with such vivid colors and those angled metal supports, it seemed as though it was designed for us. So, we incorporated it into the movie, thanks to the help of the folks at the Lawrence Berkeley lab. Ours emits gamma rays while the real thing detects them, but otherwise, it’s based on the one at Berkeley.”

The Hulk Interactive Game

For moviegoers and fans of Marvel Comics’ green Super Hero, their entrée into the world of Bruce Banner and The Hulk won’t be limited to film. With the creation of the innovative, new interactive The Hulk: The Game, “the Hulk experience” doesn’t have to end with the roll of the final movie credits.

Universal Pictures and Vivendi Universal Games (VUG) enlisted game developers to continue the Hulk experience beyond the big screen and into the hands of gamers. The Hulk: The Game upplies all of the power and personality of the motion picture combined with game play created to satisfy even the most advanced player.

From the inception of game, it was decided that The Hulk interactive experience would not only encompass the world of the film version, but would also expand upon it by having Bruce Banner and his alter ego battle villains from the classic Marvel Comics universe, as well as new enemies created especially for the game.

Additionally, game makers decided to enlarge and extend the Hulk experience by taking the characters through a brand-new storyline beyond the events of the movie; challenging players to master two different game play styles unique to both Bruce Banner and the Hulk; and featuring real-world simulation where virtually any object can be manipulated, destroyed or used as a weapon. The overriding intent was to provide fans everywhere with an enhanced Hulk experience launching in theaters and on videogame screens.

Not only can you see The Hulk—you can be the Hulk. It’s the ultimate in wish fulfillment.

The game artists, designers and producers in charge of bringing the Hulk into the interactive world visited ILM, the film’s art department, and film sets. Collaborating with the film’s animators, studying the extensive collection of models created for the film and consulting with the filmmakers every step of the way allowed for an authentic extension of key elements of the Hulk experience.

All of this time and painstaking effort paved the way for a smooth and virtually seamless transition of the characters from the Marvel Universe to the interactive realm. Acknowledging the Hulk’s worldwide recognition and appeal and recognizing the character’s overwhelming physical powers and complex, compelling emotions, game developers knew they had the opportunity to create exciting new chapters in Hulk lore by extending the franchise across mediums.

Another innovative way in which the experience of the Hulk is extended from screen to game is through the employment of “codes,” a unique integration element whereby special content in the game can only be accessed or “unlocked” when the player provides a password that is, in fact, a message or word related to the film’s plot or characters. Clues to help identify these codes will be revealed online.

One of the most intriguing developments of the Hulk leaping into the interactive arena is that the game boasts a brand-new and unique storyline that takes Bruce Banner / The Hulk, Betty Ross and other film characters one year into the future, after the events portrayed in the movie. In this all-new adventure, Bruce is betrayed by his long-time colleague and mentor, Professor Crawford, and he unwittingly releases the essence of the Hulk into an Orb, falling prey to the Leader, a villain intent on using the Hulk’s energy to unleash a relentless army of “gamma” creatures. Now Bruce must pursue his new foe through San Francisco, into Alcatraz, out of heavily guarded military installations and finally to the terrifying, surreal Freehold of the Leader himself. Only by facing his own shattered identity and gaining control of the beast within him will Bruce have the ability to destroy the nefarious intentions of the Leader.

Gamers can enjoy two different game play styles unique to both Bruce Banner and the Hulk. As Banner (with The Hulk’s Eric Bana supplying the voice and likeness), the player must employ the powers of logic and stealth, while struggling to contain the Hulk inside of him, in order to successfully complete missions. When in Hulk mode, the player must power through 25 massive, highly-detailed and fully destructible environments, directly inspired by the film and exclusive to the game, where up to 10 enemies can be challenged at once while choosing from more than 45 devastating attacks.

And the game world is never far from the real world. While the player controls the incredible power and rage of the Hulk, objects react to damage as they would in the real world, displaying behaviors consistent with the actual physical effects of mass, matter and gravity (e.g., cars bounce off walls to show body damage, glass shatters, broken pipes roll). The smashing game play is enhanced as virtually any object can be manipulated, destroyed or used as a weapon.

In the May, 2003 issue of Play magazine, the game was reported and reviewed, prompting the journalist to say that “The Hulk works as an extension of the film, meant to further the experience after you leave the theater, charged, wanting to rip things from the ground and use them as bats.” And the #141 issue (June) of Wizard boasted that “players will get the distinct impression that they’re actually playing a Hulk movie, which makes for a smashing good time.”

All of that destructive power should please the inner-Hulk inside every fan of The Hulk—from comic book to motion picture to interactive.

Headquartered in New York, Vivendi Universal Games (www.vugames.com) is a global leader in multi-platform interactive entertainment. A leading publisher of PC, console and online-based interactive content, Vivendi Universal Games’ portfolio of development studios includes Black Label Games, Blizzard Entertainment, Coktel, Fox Interactive, Knowledge Adventure, NDA Productions, Sierra Entertainment and Universal Interactive. Through its Partner Publishing Group, Vivendi Universal Games also co-publishes and/or distributes interactive products for a number of strategic partners, including Crave Entertainment, Interplay, Majesco, Mythic Entertainment and Simon & Schuster, among others.

Hulk

Directed by: Ang Lee

Starring: Eric Bana, Jennifer Connelly, Sam Elliott, Nick Nolte, Josh Lucas, Brooke Langton, Sasha Barrese

Screenplay by: Michael France, David Hayter, James Schamus

Cinematography by: Frederick Elmes

Production Design by: Rick Heinrichs

Art Direction by: John Dexter

Film Editing by: Tim Squyres

Costume Design by: Marit Allen

Music by: Danny Elfman

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for sci-fi action violence, disturbing images, partial nudity.

Studio: Universal Pictures

Release Date: June 20, 2003