Colin Firth had not read the book when Paterson and Webber approached him to play the artist Joannes Vermeer, but read the script and quickly accepted the role. He says, “It felt refreshing. It takes itself seriously, which is not a popular position in most films—it is safer to have your tongue in cheek these days.” He regarded the role as an acting challenge. “Not a lot of big things happen on the surface; the action is minimal, finely focussed drama, which must be made interesting by the characters.” He adds, “This has a parallel with the work of Vermeer.”

Firth was intrigued by the man himself. “Not a lot is known about him. He painted what modern critics could regard as cliches—images reflecting the conventions of the time. But there is an even-handed moral kindness in those paintings, showing humanity in equal terms to one another, whether milkmaid or mistress. Of the 35 paintings known today, about 20 were painted in the same corner of the same room. He lived in a lively household—eleven of his children survived, but he painted serenity in his first floor studio. In 17th Century Delft artists were craftsmen who took their civic duties seriously—they served apprenticeships, and had a union to protect their economic rights. Long before the cult of the tortured rebellious artist took over, it was perfectly possible to be a good citizen and husband.

In the film, Vermeer’s studio is a quiet retreat from a noisy household. Says Firth, “He is resigned to being surrounded by people who don’t understand what he does and keeps his world separate. When he does understand what he does allow someone in for the first time he is intrigued that Griet has an eye for color and composition and forms a mysterious bond across a vast barrier of class and age. He is sometimes pleased with what she has done, and sometimes rejects it. He attempts to distance himself from intimacy—it is too complicated for him. He doesn’t allow himself to focus on the foreground of paintings or feelings for long, and so he doesn’t find the same level of engagement each time they meet. So the relationship becomes tortuous for both of them.”

Although Firth researched the man and his paintings thoroughly, he did not learn to paint. “At my level of talent it was almost pointless,” he explains, “but what I can do is imagine that I can paint, and convince other to imagine that I can. I hold a brush and mix paints to look as if I know what I am doing. Besides, probably a great painter and a terrible painter look the same holding a brush.”

Firth found Peter Webber keen to explore the effect of different nuances on scenes. “Where a script is so affected by the tone, a change of emphasis can completely change the direction of a scene.” The actor points out parallels between filming, and the work of Vermeer. “If you look at x-rays of his paintings, you can see that he was prepared to begin with one idea and then throw that away. this can happen on a film set. Working with a crew is a huge collaborative effort. Everyone arrives in the morning and the challenge of the day is to give life to the written word, but you have to be prepared to change the ideas you brought with you that morning, in order to keep the energy and carry the room. If you are in tune, you can feel that moment. It’s palpable.”

Firth emphasises that the film is not an art lesson. “It’s an exploration of how powerful a relationship can be—like the intimacy between artist and model. A painting is unveilled and disrupts a family.”

“It was very difficult to nail anything—Vermeer’s character is utterly elusive….We don’t even know what he looked like, so it made the exercise a completely creative one for Tracy Chevalier and for the rest of us as well….It’s hard to talk about any paintings without sounding airy fairy, but there’s something going on in works that’s difficult to describe. You can call them jarring, restless, but that doesn’t do. I found myself in motion trying to chase after what it is.” (W, Nov 2003)

Scarlett Johansson on playing Griet

Casting the role of Griet, a seventeen year old girl from a sheltered home in 17th Century Holland was always going to be a challenge. Says Paterson, “it was clear this was an extraordinary role for a young girl and we had a huge amount of interest. The first time we met Scarlett she was a New York City teenager on her way to a basketball game. Second time round, she had become Griet.”

“Scarlett has been working in this business longer than I have,” says Webber, “and although she is young in years she has an old soul. She has a force of character and a face that you don’t often see on screen these days—she is hypnotic to watch, like a silent movie star.”

Scarlett Johansson found the script immediately absorbing and beautifully written. She explains, “it is so rare that you read anything that is worth the time it takes to get through it. This stood out—it was glinting. Every actor dreams of the chance to play a role like Griet—a character with such repression that you are using your face and not your words to convey emotions.” Johansson took the opportunity while filming in Delft to visit the Mauritshuis Museum to see the real painting, Girl With A Pearl Earring.

“She is strange and intriguing. I felt she was just about to do something which would tell us more about her and her life,” she says. Playing Griet, Johansson was able to empathize with her hardships. “A servant’s life was hard labor, and Griet was also trying to cope with new raw emotions. We first see her at home, which she doesn’t want to leave, but she has to and is immediately out of her element. She has no privacy—Vermeer’s wife Catharina is vicious and unrelenting; the other maid is resentful; Maria Thins is always watching her; and Vermeer lurks in his studio, refusing to engage with the rest of the household. At the same time her relationship with her home is changing.”

But Vermeer senses a connection with Griet. He realises she sees physical things the way he does, and gradually allows her to become involved in his work. “Their relationship becomes tender, through their mutual involvement in his paintings,” explains Johansson. “At the same time she is becoming involved with Pieter, the son of the market butcher. He is a tradesman, goes to Church every Sunday and offers an enticingly simple way of life that is familiar to her. He offers a mutual courtship that she could so easily slip into, if she had not met Vermeer. With the painter she tastes a kind of passion that is beyond her comprehension, and casts a shadow on her previous life.”

Johansson hopes that GIRL WITH A PEARL EARRING will send the cinema audience away with some kind of bittersweet feeling of hope, while recognizing that some of the most romantic feelings you have in your life come to nothing. She says, “The raw emotion of a girl who is in love and not able to express it is universal, because very often you can’t have what you love.”

The Director

The producers asked Peter Webber to direct the film. Paterson explains that “although this is Peter’s feature film debut, we had already worked with him for several years, first as an editor (he edited Anand Tucker’s first drama Saint-Ex) and then as a documentary director—covering a diverse range of subjects from Crash Test Dummies to Wagner.” His first dramas included the controversial “Men Only” for Channel Four, charting a five-a-side football team’s decline into debauchery and sexual violence.

“Peter was always going to make movies”” says Paterson. “His knowledge of cinema is enviable, and it took no time at all for actors of the caliber of Colin Firth, Scarlett Johansson and Tom Wilkinson to decide they wanted to work with him. Peter, Olivia and I all started out in the cutting room and we share a fascination with the nature of story-telling on film. ”

For Webber, who had studied art history and was already fascinated by Vermeer, the story has the essential elements for drama, money, sex and power. He says, ‘Vermeer lived in a household full of noise and chaos. He was under huge financial pressure to paint more and faster, to feed his family. Yet his paintings achieve such tranquility. I was thrilled by how Tracy’s story reflected his work, how the intimate, the understated, somehow becomes epic. Griet’s predicament is heartbreaking. The repressed romantic obsession that builds between Griet and Vermeer inspires him to paint her—but the perfection of that painting will lead to her downfall. She knows he will be ruthless, understands that their relationship must be sacrificed if the choice is between her and a truly great work. That understanding is, after all, what drew him to her in the first place. The legacy of her time with Vermeer is one of the greatest pictures ever painted.”

Re-creating Vermeer’s World: Design and Cinematography

“The scene is a familiar room, nearly always the same, its unseen door is closed to the restless movement of the household, the window open to the light. Here a domestic world is refined to purity.” — Lawrence Gowing: “Vermeer. ”

“The look of the period is, of course, very well documented in the extraordinary paintings of the Golden Age of 17th century Holland,” says production designer Ben van Os. “We conceived Vermeer’s house to give us that sense of frames within frames so familiar from the paintings; a passageway leading from the canalside into the courtyard and the ground floor rooms connected by open doorways, leading the eye through the house to give a feeling of space—and lack of privacy. Griet should always feel watched.”

“Peter (Webber) and I also felt that many of the paintings gave an idealized view. We took the decision to introduce a gritty reality, particularly to the exterior scenes—filling the streets with livestock and mud.”

The interiors were divided into three distinct worlds. Griet’s family home is a monochrome ordered Calvinistic abode in the poorer quarter; the Vermeer family lives in lurid Catholic chaos with lots of paintings on the walls (Vermeer was also a dealer who sold the work of others) and the vivid colors of popery; his rich patron Van Ruijven’s world is opulent, with curiosities from around the world. This is where the real power lies.

“I wanted the Vermeer house to be chaotic—downstairs” says Webber. “The house was full of children and noise. It looked out onto a canal which must have been very smelly. The main square with its taverns and markets was just half a block away. Yet Vermeer created; paintings which seem to define tranquility and perfection. So we were determined that the studio, the room that contained that familiar, almost holy corner represented in so many of the great paintings, should be the magical space. Up there is Vermeer’s private world—a world which he gradually allows Griet to share because she alone understands why it is special. Ben built gorgeous sets, but he is also a great set dresser, making the world believable, lived in and totally convincing.”

Cinematographer Eduardo Serra used different film stocks for the different worlds, capturing the rich dark colors of the downstairs of Vermeer’s house and saving something for the painter’s studio.

“The shooting schedule worked in such a way that we saved Vermeer’s studio for last” remembers Paterson. “One day I was watching the stunning footage from elsewhere in the Vermeer house and reminded Eduardo of the earlier discussions about saving such beauty for the studio. He nodded that he hadn’t forgotten. And when I saw what he did in the studio, it was breathtaking. He took it to another level altogether.” “Eduardo’s work was quite extraordinary” adds Webber. “He had decided how he wanted every frame to be lit and seemed able to achieve it almost instantly.”

Dien van Straalen’s costumes were the final element in creating an authentic world. “Most of the time you should hardly be noticing the costumes,” says Webber. “Great costume designers make clothes that actors feel comfortable in, and it helps create the feeling that you are inhabiting a real world. Catharina’s costumes are exquisite and showy because that’s who she is, but even she has to wear the same dress on a number of occasions to reflect the financial burdens of the family. Dien’s triumph was to create costumes that subconsciously help in the telling of the story.”

American Cinematographer (January 2004 by Ron Magid)

Based on Tracy Chevalier’s historical novel, Girl With a Pearl Earring pierces the mystery of Johannes Vermeer’s enigmatic painting by presenting an imaginary liaison between the artist (Colin Firth) and his subject, a servant named Griet (Scarlett Johansson). The film’s director of photography, Eduardo Serra, ASC, AFC, says that focusing on a story about a great Dutch painter presented him with the perfect opportunity to explore the relationship between painting and “painting with light,” as cinematography is often described. In fact, Serra calls filming Girl With a Pearl Earring “a dream.”

Serra, who earned an Academy Award nomination for The Wings of the Dove, notes that “classic painters respected the play of light, so there is a close relationship between their paintings and modern cinematography. But for me, respecting light isn’t a goal. Rather, it’s a starting point for storytelling, just as for painters it once was a starting point for art. Some have been kind enough to say that my cinematography on Girl With a Pearl Earring looks like Vermeer’s paintings, but in fact, I didn’t do anything that I wouldn’t have done if I were telling that story on that set about someone other than Vermeer. If you took The Godfather and changed the costumes to the 17th century, everyone would say, ‘Gordon Willis has recreated Rembrandt.’ I didn’t want to make Girl With a Pearl Earring a visual statement, because photography shouldn’t take precedence over the story. The first thing I said to [director] Peter Webber was ‘People shouldn’t leave the theater saying ‘Every frame is a painting,’ because the most important things are the emotion and the story.’

With this goal in mind, Serra strove for simplicity, relying on naturalistic lighting and a careful blend of film stocks to create the picture’s rich palette…

“I believe the best use of widescreen is not necessarily landscrape,” the cinematographer continues. “I think it’s often better for intimate stories because it allows two or more elements to relate in the frame. It was one of our most important tools on this film because it strongly relates to the way Dutch painters used frames within frames in their work. It also enabled us to show light coming through a window and falling off, rather than reaching the opposite wall.”

Serra used Fuji’s high-speed daylight-balanced stock, Reala 500D, for day exteriors. which were filmed on the backlot at Delux Studios in Esch, Luxembourg. Production designer Ben van Os redressed the exterior set so that it would pass for Delft, Vermeer’s home town, circa 1665. “I used daylight stock for the first time because we were shooting in the winter and the days were very short, and I wanted to push through to 1,000 ISO almost every day and still have a color-balanced negative,” says Serra. “I think it worked very well.”

The film’s narrative unfolds over nine months, but the production shot for just over three, so Serra used filtration to suggest the changing seasons. “I didn’t use any filters for spring and summer scenes, but I made corrections to winter scenes with 80 and 82-blue filters to give them a colder feel.”

Vermeer’s house, which includes the basement servant quarters, a ground floor and an upstairs studio, was a practical set built onstage at Delux Studios. To film most interior scenes, Serra used Kodak’s new Vision2 500T 5218, and he often pushed it to make the most of low light levels. “The 5218 had just been released when we started shooting,” he recalls. “It responded [to pushing] well. I could go in the direction of rich color without violence.”

One of the film’s most remarkable sequences is a lavish candlelit dinner party that Vermeer arranges for his patron, Van Ruijven (Tom Wilkinson), who is withholding a commission the artist needs to pay his bills. Sensing Vermeer’s desperation, the sadistic Van Ruijven also notices a growing intimacy between master and maid. This leads him to contrive a new commission for Vermeer to paint Griet as the Girl With a Pearl Earring. “The dinner party is a long, important scene with plenty of people and lots of dialogue,” says Serra. “It establishes characters and sets the stage for the central drama. We shot it with two cameras, and I didn’t try to light it in a realistic way. When lit realistically, candlelit scenes are very strong and dramatic visually, and I thought that wouldn’t be appropriate in this film. Our story deals with Vermeer and daylight, not La Tour and candlelight. and I didn’t want to do a history of painting. The important things in the scene are the relationships among the characters, so I was rather traditional in my approach. I wanted to make it believable, not distracting.” Serra lit the scene with a combination of Kino Flos through heavy diffusion and Chinese lanterns gelled with full CTO.

For a scene that shows Griet making an eerie, candlelit trek through the house in the middle of the night, Serra again avoided realistic lighting. “Generally, I tried to light the house more richly than it would have been with real candles,” he notes. “In reality, the candle wouldn’t illuminate the walls or the corners of a room.”

Little is known about Vermeer, who left 35 paintings behind when he died at age 43. But thanks to clues in many of his canvases, a great deal more is known about his studio. “More than any other painter of that period, Vermeer consistently tried to analyze what effect natural light had on a room and on a face,” Serra remarks. “At that time, it was very important to be accurate in reproducing light because painting was theway to capture the world.” The cinematographer saw Vermeer’s studio as a place magically apart from the rest of the artist’s day-to-day existence, and he employed Kodak Vision 500T 5263 to give the setting a distinctly different feel… “I often like to change stocks when I have different situations, and I think using a different stock helped give Vermeer’s studio a softer look to separate it from the rest of the house. It was kinder to the actors’ faces, and the colors were a little subtler and more subdued than what we have in the rest of the film. Many areas of the house are quite dark, but the studio is light. It’s all about light. We wanted to keep the emphasis on the characters, but in Vermeer’s studio, light is also one of the characters.

“Sometimes we had to be very specific about lighting this set because we had to respect certain Vermeer paintings,” he continues. “About the only thing we really know about Vermeer is how that side of his studio looked. Like all painters, he had windows to the north so that the light wouldn’t change much throughout the day. Ben van Os built quite an accurate reproduction of it.”

Some cinematographers might have felt constricted by having to light the space almost exclusively from the windows, but Serra says he wouldn’t have done it any other way. “I knew that I would have to be respectful of the light coming through the windows and be as honest as possible, but that is what I like to do anyway,” he says. “It’s very disruptive to have light coming from somewhere else when you know where it’s supposed to come from. I respect logical, natural sources, not because classic painters did, but because I like it. It’s not a rule or moral obligation, it’s my taste. My ideal is one soft source. I don’t like spotlights putting shadows everywhere, and I never use backlight or rimlights around the head and hair for separation. I think it’s quite distracting. I like what soft light does on faces, and I also like the contrast soft light gives to the image. So I just organized the light coming through the windows, allowed it to fall naturally, and then took advantage of it.” To create the daylight, Serra’s crew placed four 24-light Dinos going through two frames of full gridcloth outside the windows…

As Griet transitions from being Vermeer’s assistant to being his model, the painter’s studio undergoes a fascinating metamorphosis, evolving from a very dark, mysterious place into a bright, welcoming one. “We were trying to achieve that,” Serra says with pride. “We simply moved our small lights to change the mood—subtle touches that made it feel either empty and cold or warm and sensual. But the basis lighting setup outside the windows remained the same.”

Serra’s approach to lighting Vermeer undergoes a similar evolution. The artist is first shown in shadow, but then Griet spots him watching her from the darkness of his studio and gradually brings him into the light. “Originally, we were supposed to see Vermeer fully earlier in the film,” reveals Serra. “But the decision to keep him in shadow and reveal him so slowly—we only see him clearly at that dinner party—was not only a photographic decision, but also a directorial and editorial decision. I didn’t use a very complicated lighting scheme for Vermeer; it flowed from the story and the situation. He’s always sidelit in the studio, with his profile to the light, so he’s much more contrasty than Griet. Letting the light drop off from the windows in that big room made the rest of the house feel heavy with deep shadows.

Given Serra’s rigorous quest for purity in his images, it is perhaps not surprising that he decided to forgo a digital intermediate (DI) on Girl With a Pearl Earring. “When we started shooting, we hadn’t made a decision about that yet,” he recalls. “After I saw the first printed rushes, there was something about the faces, the skin tones, the color, the richness and brightness, that I was afraid we would lose if we went digital. When you’re happy with what you get on film, why go digital?”

Production Design in Detail

Director Peter Webber and his production team created a living, breathing, fully dimensionalized portrait of the 17th-century Dutch town of Delft on a budget of just $10 million. The secret to their success lay in the angle of attack. Webber is a passionate admirer of Stanley Kubrick’s 18th-century epic, “Barry Lyndon.” But upon reading Olivia Hetreed’s screenplay for “Pearl Earring,” Webber saw a key difference between Kubrick’s film and the one he was about to make. “Kubrick was obsessed with the spectacle and manners of the period,” says Webber. “So he staged these elaborate and expensive set pieces. My film was about the intimate relationships within a single household.”

“The characters who pass through Vermeer’s house come from a broad spectrum of society, from the very wealthy to the very poor,” says Webber. “You get a microcosm of 17th-century Holland under one roof. So the film is, in a sense, an intimate epic.”

Production Design

Finding a production designer who could bring this distilled drama to the screen proved difficult. “The various British production designers whom I spoke to approached the film a bit like it was a museum piece,” says Webber. “They wanted to get all of the period details exactly right, and were slightly scared of not getting it right.”

When Webber met Ben van Os he knew he had found the right person. “Ben is Dutch; this story is in his blood,” says the helmer. “So he wasn’t intimidated by the period obligations. He was much more interested in story and character. How are we going to create this mood? Ben said, ‘We’ll take this from this period and this from that period.’ It was music to my ears.

“The most important things are the story and the characters. I really don’t care if I’m going to get a letter from some expert in Dutch architecture saying, ‘That roof design wasn’t used until 17 years after your movie takes place.'”

Van Os created a cross-section of Dutch society by building three interior sets: the drab monochromatic, Calvinistic home of Griet; the lurid, painting-filled Catholic chaos of the Vermeer house; and the mansion of Vermeer’s wealthy patron, van Ruijven (Tom Wilkinson , filled with curios gathered on his world travels and eerie stuffed animals, which convey van Ruijven’s predatory nature.

The Vermeer house presented the biggest challenge. Van Os constructed the three-story set on one of the largest soundstages in Luxembourg. “We wanted the house to give us that sense of frames within frames so familiar from Vermeer’s paintings,” says van Os. “We built rooms with connecting doorways that led the eye through the house to give a feeling of space—and lack of privacy. We wanted Griet to always feel watched because the film is about being observed, either by Vermeer as he paints her, or by the other family members with their various agendas.”

Van Os knows that the little details give this cloistered world authenticity. “For instance, the windows are all exact reproductions of the those that were used at the time,” he says. “That was a big undertaking, quite expensive. We went to a company that restores all kinds of windows in old churches and historic buildings and had them build them for us.”

For the exteriors, Webber and van Os spread dirt and trash to give the streets the feel of a crowded city. “I was obsessed with getting animals—dogs, livestock—into as many shots as I could,” says Webber, “because it brings a breath of life to the piece.

Costume Design

The distillation process extended to the wardrobe as well. “I wanted a stripped-down look,” says Webber. “If I dressed all the actors in the real costumes of that era, they would be wearing ruffles and baggy outfits. I didn’t want to put Colin Firth in that. For a modern audience he’s going to look too costumey. So we came up with a look we jokingly called period Prada, to give the clothes sleek lines. I called it my Vermeer filter: take the real clothes from the period and reduce them to their essence.”

Costume designer Dien van Straalen combed through second-hand clothing and furniture stores, Indian silk shops and garment marts throughout London and Holland in search of period fabrics. Old curtains and slipcovers were converted to jackets and dresses, and aged with sandpaper. The wardrobes for each character varied from prosaic to grand. Again, the clothes made up a cross-section of the 17th-century Dutch society. “We used pale colors for Scarlett Johansson to give her the drab look of a poor servant girl,” van Straalen explains.

As for Vermeer, “obviously he was not a wealthy man, though he was considerably better off than Griet. So I wanted to keep him as plain as I could. He sometimes had to go out to social events, so we gave him one aged black dress suit with a simple white collar and a bit of braid.

“Vermeer’s patron, van Ruijven, wants to control Vermeer and enjoys his power over other people. For me he was a peacock strutting around with his money. I used more braids and more gold, big hats with feathers, and cloaks. We have costume makers in Holland who used to work for the opera so they know exactly how to make fancy clothing from that period.”

Makeup and Hair

“The makeup for Scarlett Johansson was very simple,” says makeup and hair designer Jenny Shircore. “We just had to keep her skin looking milky, thick and creamy. This required some makeup because Scarlett has spots and things that happen to a 17-year-old. We wanted to present her as if she had no makeup on. We gave her a little bit of help by bleaching her eyebrows, because in the Vermeer paintings it’s all about skin and face, nothing else gets in the way, so you eliminate those other features.”

Almost all of the actors wore wigs, which presented problems. When Johansson’s wig arrived a couple of days before shooting, it had the wrong color and texture. “It was a nightmare,” Shircore laughs. “I didn’t dare say a word to Peter, because I thought: ‘We must sort this out without giving him a headache.’ We were up all night dyeing, straightening, curling and redyeing the wig.”

“For Vermeer’s wife, Catharina (Essie Davis), I used a very simple Dutch hairstyle. The women wound their hair round the back of their heads. There comes a point when you’ve finished the hair, it can’t be wound anymore because the length is used up. Instead of neatly pinning it away, we let the ends splay out, because in looking at references, little drawings and prints, we found that that’s what they did. Once you’re actually working within a period, the hairstyles evolve very naturally.”

Production notes provided by Lionsgate Films.

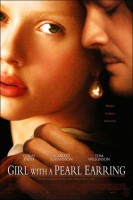

Girl with a Pearl Earring

Directed by: Peter Webber

Starring: Colin Firth, Scarlett Johansson, Tom Wilkinson, Essie Davis, Alakina Mann, Cillian Murphy, Judy Parfitt, Leslie Woodhall

Screenplay by: Olivia Hetreed

Cinematography by: Eduardo Serra

Film Editing by: Kate Evans

Music by: Alexandre Desplat

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for sexual content.

Studio: Lionsgate Films

Release Date: December 12, 2003