Taglines: It brings magic back to the cinema.

Paris, Texas movie storymine. Four years after he disappeared without a trace, Travis Henderson reemerges in the small US border town of Terlingua, Texas, where his Los Angeles residing brother Walt Henderson must retrieve him. Travis, looking a little worse for wear, is initially mum about everything that has happened in his life in the intervening years, especially why he and his wife, Jane Henderson, individually abandoned their lives and their marriage which resulted in who was their then four year old son Hunter Henderson being dropped off with Walt and his wife, Anne Henderson.

Believing that Travis and Jane had both since died, Walt and Anne have raised Hunter as their own, he who does not generally remember either of his biological parents. Travis’ return is thus bittersweet for Walt and Anne who have to decide what to do about Hunter and his relationship with his biological father, which nonetheless is strained in Hunter not really knowing Travis.

Travis’ return is not by accident as it is just the next step in he reconciling his life with regard to Hunter which involves his want to go to Paris, Texas, where he has purchased some property. But that reconciliation takes a turn when Anne divulges some information to him, which leads to a trip to Houston to make that reconciliation perhaps not more holistic but just in Travis’ mind.

Paris, Texas is a 1984 road movie directed by Wim Wenders and starring Harry Dean Stanton, Dean Stockwell, Nastassja Kinski, and Hunter Carson. The screenplay was written by L. M. Kit Carson and playwright Sam Shepard, while the musical score was composed by Ry Cooder. The film was a co-production between companies in France and West Germany, and was shot in the United States by Robby Müller.

The plot focuses on a vagabond named Travis (Stanton) who, after mysteriously wandering out of the desert in a dissociative fugue, attempts to reunite with his brother (Stockwell) and seven-year-old son (Carson). After reconnecting with his son, Travis and the boy end up embarking on a voyage through the American Southwest to track down Travis’ long-missing wife (Kinski).

At the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, the film won the Palme d’Or from the official jury, as well as the FIPRESCI Prize and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. It went on to win other honors and critical acclaim.

Film Review for Paris, Texas

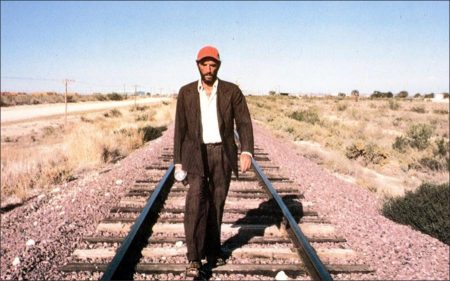

The man comes walking out of the desert like a Biblical figure, a penitent who has renounced the world. He wears jeans and a baseball cap, the universal costume of America, but the scraggly beard, the deep eye sockets and the tireless lope of his walk tell a story of wandering in the wilderness. What is he looking for? Does he remember?

Wim Wenders’ “Paris, Texas” (1984) is the story of loss upon loss. This man, whose name is Travis, was once married and had a little boy. Then that all went wrong, and he lost his wife and child, and for years he wandered. Now he will find his family and lose it again, this time not through madness but through sacrifice. He will give them up out of his love for them.

The movie lacks any of the gimmicks used to pump up emotion and add story interest, because it doesn’t need them: It is fascinated by the sadness of its own truth. The screenplay was written by Sam Shepard, that playwright of alienation and rage, and it reflects themes that repeat all through Wenders’ career. He is attracted to the road movie, to American myth, to those who stand outside and witness suffering. Travis in “Paris, Texas” is like Damiel, the guardian angel in “Wings of Desire.” He loves and cares, he empathizes, but he cannot touch. He does not have that gift.

The movie’s story is simply told. Travis (Harry Dean Stanton) asks for water at a backroads gas station, collapses, is cared for at the local hospital. His brother Walt Henderson (Dean Stockwell) comes to fetch him, but when they stop on the road he starts walking away again, down the railroad tracks. He will not speak.

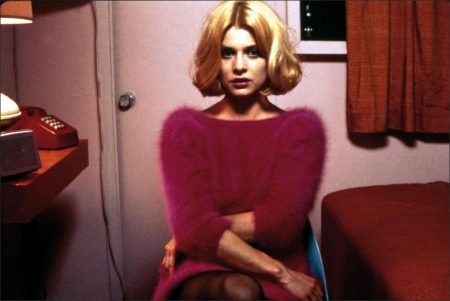

And when he finally does start speaking, it’s as if he is haltingly reassembling a self that he lost track of. Walt and his wife Anne (Aurore Clement) live in Los Angeles with Hunter (Hunter Carson), who is Travis’ son. We gradually learn pieces of the story: Hunter was left with the Hendersons by Travis’ wife Jane (Nastassja Kinski), who could no longer care for him, but who sends a check every month from a bank in Houston.

Travis is not insane, not acting out his alienation. He is simply lost in grief, despairing at the way his marriage was joyous for a brief time and then was destroyed by his own drinking and jealousy. He stays for a time with the Hendersons, slowly wins Hunter’s trust, walks home with him from school in a sweet little scene where they copy each other’s gaits. Then he has a serious conversation with Hunter that leads to them getting into Travis’s old Ford pickup and driving to Houston to find Jane.

The movie is always compared to John Ford’s “The Searchers,” a film in which a man wanders in the desert to look for a young woman lost to the Indians. Another film said to be inspired by “The Searchers” is Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” where the hero (also named Travis) tries to rescue a young woman from the clutches of a pimp. In the Wenders and Shepard telling, Jane is discovered working in a sex club, where her specialty is sitting behind one-way glass and talking with her customers over a telephone. The buried theme in each case is the need to save the woman from what is perceived as sexual bondage. All three heroes–those played by John Wayne, Robert De Niro and Stanton–are somewhat misguided in their quest, not quite understanding the role of the woman.

The journey from Los Angeles to Houston includes many long talks between Travis and Hunter, and I was reminded of Wenders’ “Kings of the Road” (1976), where two men share a long journey and talk especially about women, how they need them and do not understand them. Travis and Hunter talk obliquely about the missing wife and mother, but they also cover the Big Bang and the theory of relativity. Although they are sharing the front seat of the truck, they sometimes speak over walkie-talkies. This mechanical intervention in their conversation is reflected later, when Travis talks with his wife on the telephones in the booths at the sex club.

“Paris, Texas” is as linear as an arrow. Travis is hauled back from despair and reunited with his brother’s family and Hunter. The more he sees the family the more he feels that Hunter belongs with his biological mother. The journey takes them to Houston, and then everything narrows down to the heartbreaking scenes in which Travis and Jane try to explain themselves to one another.

Their first conversation is halting and painful, as Travis tries to determine if Jane goes home with her customers for money. She does not. We understand that Travis asks not out of jealousy, but because he is forming a plan. In the second conversation, even though Jane cannot see him and his voice is distanced by the tinny sound of the phone, Travis turns his back to the window. He cannot even look at Jane while telling her a story.

“I knew these people,” Travis begins, in one of the great monologues of movie history. “These two people. They were in love with each other. The girl was very young, about 17 or 18, I guess. And the guy was quite a bit older. He was kind of raggedy and wild. And she was very beautiful, you know?”

He tells of a time when even a trip to the grocery store was an adventure. When he would quit jobs just so he could be at home with her. And then how the jealousy began to eat at him: “Then he’d yell at her and start smashing things in the trailer.” When Jane repeats, “the trailer?” it is clear she knows this is Travis (I think she knows sooner, and gives it away with a sideways flicker of her eye). He continues with his story, ended when the marriage is in wreckage and he awakens with the trailer on fire: “Then he ran. He never looked back at the fire. He just ran. He ran until the sun came up and he couldn’t run any further. And when the sun went down, he ran again. For five days he ran like this until every sign of man had disappeared.”

This confession inspires Jane to turn her back to the window and tell her own story. At one point she turns off the light in her cubicle and he turns a light to his face and she can even see him. They never touch. He tells her that Hunter is waiting for her in the Meridian Hotel, Room 1520. “He needs you now, Jane. And he wants to see you.”

The film ends with the mother and child reunited. In a decision that is both dramatically and cinematically inspired, Travis watches their meeting from the rooftop of a nearby garage, and then drives away. There is the same feeling as when John Wayne, in “The Searchers,” restores the missing girl to her family and then looks on, alone again and forgotten, before turning to walk back into the wilderness.

Practical and logical objections can be raised about this story. Was Travis right to take Hunter away from Walt and Anne? Can Jane care for him? Could Jane work in the club and not be a prostitute?

But never mind. Wenders uses the materials of realism but this is a fable, as much as his great “Wings of Desire.” It’s about archetypal longings, set in American myth. The name Travis reminds us of Travis McGee, the private investigator who rescued lost souls and sometimes fell in love with them but always ended up alone on his boat. The Texas setting evokes thoughts of the Western, but this movie is not for the desert and against the city; it is about a journey which leads from one to the other and ends in a form of happiness.

Wenders is part of that circa-1970 flowering of talent known as the German New Wave (it includes also Herzog, Fassbinder, Schlondorff, von Trotta). He has always been fascinated by American movies and music; many of his films are set at least partly in the U.S. The music in “Paris, Texas” is by Ry Cooder, and it’s lonely and filled with distance (they collaborated again on the Cuban music documentary “The Buena Vista Social Club”). The photography by Robby Muller contains the sense of a far horizon beyond every close shot. The Shepard dialogue lacks all flourish and fanciness, and is about hard truth, long rehearsed in the mind.

Then there are the miracles of the performances by Harry Dean Stanton, Nastassja Kinski and Hunter Carson (the son of Karen Black and L.M. Kit Carson). Stanton has long inhabited the darker corners of American noir, with his lean face and hungry eyes, and here he creates a sad poetry. Kinski, a German, perfects the flat, half-educated accent of a Texas girl who married a “raggedy” older man for reasons no doubt involving a hard childhood. Young Carson, debating relativity and the origin of the universe, then asking even harder questions such as “why did she leave us?” has that ability some child actors have, of presenting truth without decoration. We care so much for their family, framed lonely and unsure, within a great emptiness.

Paris, Texas (1984)

Directed by: Wim Wenders

Starring: Harry Dean Stanton, Nastassja Kinski, Dean Stockwell, Aurore Clément, Claresie Mobley, Hunter Carson, Edward Fayton, Justin Hogg, Tom Farrell, John Lurie, Sally Norvell

Screenplay by: L.M. Kit Carson, Sam Shepard

Cinematography by: Robby Müller

Film Editing by: Peter Przygodda

Costume Design by: Birgitta Bjerke

Art Direction by: Kate Altman

Music by: Ry Cooder

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: 20th Century Fox

Release Date: November 9, 1984

Views: 182