Lola movie storyline. It’s been over ten years since the end of WWII, and the West German economy is booming largely due to reconstruction. Straight-laced, refined, wealthy and regimented von Bohm is hired by Mayor Völker as the new Building Commissioner in his West German city, von Bohm new to the city. Kleinermans, von Bohm’s predecessor, ran a lax, undisciplined building department, resulting in the major shrewd contractors, especially Schuckert, being able to sneak and bribe their way into building whatever they want.

Schuckert’s activities are despite Kleinermans and now von Bohm’s assistant, Esslin, never having agreed with what is happening in the construction business in the city. Usually reserved von Bohm quickly falls for a young woman he meets named Marie-Louise. He is unaware of two fundamental aspects of her being. First, she is the daughter of the faithful Prussian housekeeper he has just hired, Frau Kummer. And second, although being a classically trained singer, Marie-Louise works largely as Lola, a performer at a sleazy cabaret, where the women also ply their trade upstairs at the whorehouse.

Most of the bureaucrats and elected officials, including Esslin and Mayor Völker, know Lola as they frequent the cabaret and whorehouse, Esslin who even works as a drummer in the cabaret’s band. Lola is largely married Schuckert’s kept woman, he the biological father of Lola’s now adolescent daughter, Marie, of which he is aware. Like most of her fellow whores, Lola doesn’t much like her life, she yearning for respectability. She doesn’t like false artifice, as she is ashamed of her own double life.

As such, Marie-Louise dreams of a life with von Bohm, she and Esslin the only two people who know the entire situation between her and von Bohm. The question becomes what the repercussions are if von Bohm finds out about her life as Lola, those repercussions not only on their relationship but also the nature of the construction business in the city.

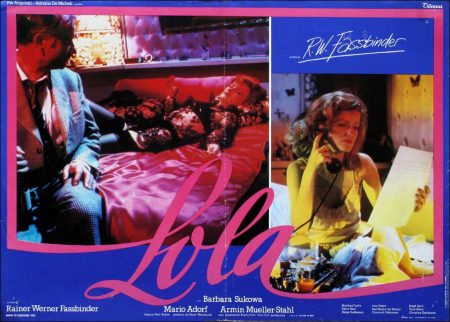

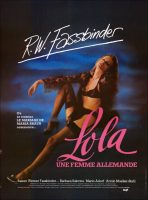

Lola is a 1981 West German film directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and is the third in his BRD Trilogy. The first film in the trilogy is The Marriage of Maria Braun and the second is Veronika Voss. It stars Barbara Sukowa, Armin Mueller-Stahl, Mario Adorf, Christine Kaufmann, Günther Kaufmann, Helga Feddersen, Karin Baal, Elisabeth Volkmann, Ulrike Vigo and Karl-Heinz von Hassel.

The Candy-Colored Amorality of the Fifties

“Gray literature” is the term German film historians use to describe the material written purely for publicity purposes and made available to the press, but not meant for official publication. Often this gray literature, which is only accessible to film journalists, is indirectly responsible for a film’s reception. The press work for Lola was handled by Karsten Peters (and Fassbinder quickly came up with a part for him in the movie: Peters played the local reporter). Peters had a delicate job to perform, because on the one hand they wanted the press to believe that the new Fassbinder film was a remake of The Blue Angel, but at the same time, they had to avoid this impression for copyright reasons.

In the press booklet Fassbinder explained how the movie came about: it was a story in itself, he said. “After I made Despair with Dirk Bogarde, he wrote me a letter saying that, although he didn’t actually want to make any more films, he would like to do another film with me—and he wanted it to be Heinrich Mann’s Professor Unrat. I thought this was an exciting idea. But my writers, Peter Märthesheimer and Pea Fröhlich, said that the story in the novel as it is didn’t interest them very much. In the meantime, I was also at the point of thinking to myself that the period in which the novel is set—i.e., before World War I—didn’t interest me very much either. I am interested in the fifties.”

The attempt to transfer the story to another epoch failed at first, however. Märthesheimer went into seclusion for six weeks and wrote a new version—at his own risk, because he wanted to prove that only a free adaptation would correspond to Fassbinder’s ideas. (Even Josef von Sternberg’s screen adaptation of the novel, The Blue Angel, had deviated from the original plot. The film ignored the critical references to the period, stressing instead the melodrama; left out most of the story of the marriage; and turned the “artiste” Rosa Fröhlich into the nightclub singer Lola Lola.)

The second attempt succeeded because Märthesheimer freed himself from what had become a historical milieu. Fassbinder wanted to make a film about the fifties, but the theme of the high-school teacher as small-town tyrant, a figure from the era of Kaiser Wilhelm, simply did not fit into the period of the German economic miracle.

The protagonist had to have something to do with the reconstruction of the country, so a building commissioner seemed to be the ideal profession. A big-time building contractor as his antagonist formed a logical constellation. The whore fit in with the time, as a virtual representative of the fifties, because—as Fassbinder explained in the press booklet—“the years from 1956 to 1960 were more or less the most amoral period that Germany ever experienced.”

This brought about “a completely new, completely original story,” continued the filmmaker. The lawyers took a different standpoint; the producer wanted to avoid a lawsuit. They agreed to have a nonpartisan legal opinion drafted on behalf of Leonie Mann (Heinrich Mann’s heir) and Trio Film. Paragraph 24 of the copyright law stipulates that an independent work that has been created in free adaptation of the work of another party can be published and exploited without consent. The decision about whether the work has been adapted freely or not is a matter of interpretation; it is a gray zone, and since the producer did not want to risk a plagiarism trial, they agreed on a settlement out of court.

“He didn’t like preparatory talks. He also didn’t like intermediate talks or final discussions, but preparatory discussions least of all,” reports Peter Märthesheimer. Script conferences like those he used to have as a TV producer didn’t exist with Fassbinder. “You would be invited to dinner at his apartment and would talk about all sorts of things, but not about the project. “And then at some point he would take you aside and give you his order.”

In the case of Lola, the work was not immediately done to the customer’s satisfaction, but Fassbinder accepted the second version without any changes. However, during the shooting—this was his way of appropriating a script—he began to rewrite…without consulting the screenwriters. Märthesheimer: “I’m sitting there watching the rough cut of Lola and feeling quite happy, and all of a sudden a black G.I. walks into the apartment….”

In the opening credits, under “screenplay,” the third name listed is Fassbinder’s: the final version stems from the director. The new ending reflects a truly essential change. Even after their marriage, which integrates von Bohm once and for all into small-town society, Lola remains Schuckert’s own private whore. That was the last scene in the screenplay. The preceding scene—in the screenplay—the usual Sunday churchgoing, the election poster reading “No Experiments” summarizing the political tone of the situation—was changed by Fassbinder.

The marriage: Lola all in white. The bride bids farewell, gets into her red convertible, and meets with the building contractor—Fassbinder hardly needed to change the screenplay there. This is followed by a new closing scene: Esslin and von Bohm walking in the woods; von Bohm’s assertion that he is happy does not sound convincing. This gives the false happy ending a different accent: von Bohm has willingly resigned himself to his fate, and he appears to recognize that Lola is betraying him. Otherwise, Fassbinder hardly touched the dramaturgy, the narrative flow, the sequence of scenes, or the dialogue, except for minor rearrangements and accentuations that are typical of directorial changes in the filming of a screenplay.

Lola (1981)

Directed by: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Starring: Barbara Sukowa, Armin Mueller-Stahl, Mario Adorf, Christine Kaufmann, Günther Kaufmann, Helga Feddersen, Karin Baal, Elisabeth Volkmann, Ulrike Vigo, Karl-Heinz von Hassel

Screenplay by: Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Pea Fröhlich, Peter Märthesheimer

Production Design by: Raúl Gimenez, Udo Kier, Rolf Zehetbauer

Cinematography by: Xaver Schwarzenberger

Film Editing by: Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Juliane Lorenz

Costume Design by: Barbara Baum, Egon Strasser

Art Direction by: Helmut Gassner

Music by: Freddy Quinn, Peer Raben

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: United Artists Classics (US theatrical)

Release Date: August 20, 1981 (Germany), August 4, 1982 (United States)

Views: 181