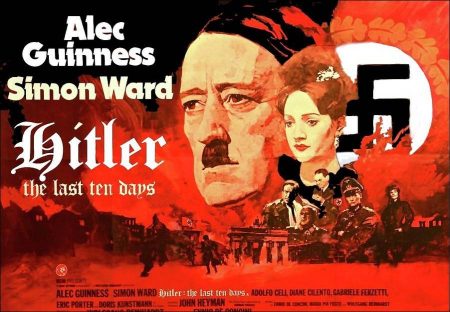

Taglines: Do you know the truth about Hitler and his last 10 days in the Berlin Bunker?

Hitler: The Last Ten Days movie storyline. Alec Guinness plays against stereotype, imbuing his Adolf Hitler with an introverted solemnity in Ennio De Concini’s Hitler: The Last Ten Days. Set almost entirely inside Hitler’s Berlin bunker, the film chronicles the dying days of the Third Reich as the Allied armies close in on Berlin. Guinness’s Hitler is an enclosed depressive who sinks slowly into madness, depression, and ultimately suicide as his 1,000-Year Reich collapses around him.

Hitler: The Last Ten Days is a 1973 British-Italian biographical drama film depicting the days leading up to Adolf Hitler’s suicide. The film stars Alec Guinness and Simon Ward, and features an introduction presented by Alistair Cooke; the original music score was composed by Mischa Spoliansky. The film is based on the book Hitler’s Last Days: An Eye-Witness Account (first translated in English in 1973) by Gerhard Boldt, an officer in the German Army who survived the Führerbunker. Location shooting for the film included the De Laurentiis Studios in Rome and parts of England.

Film Review for Hitler: The Last Ten Days

“Hitler: The Last Ten Days” is a movie that doesn’t supply many answers about the evil man’s death, and doesn’t even seem to understand what the questions are. The death trip that went on inside Hitler’s Berlin bunker has a grisly fascination of its own, but this movie doesn’t get inside the characters; it isn’t demented enough, somehow. If poor Visconti hadn’t entirely wigged out with “The Damned,” he might have been the right director for this assignment.

As it is, we get a fashion show (heavy on the red lipstick, please) and a lot of secondhand historical gossip. Hitler and Eva Braun, it appears, spent their last days together in much the same manner as Bonnie and Clyde. They listened to records, got tender and were just on the blink of – at last! – consummating their mutual romantic fantasies when the Russians and/or Texas Rangers had to spoil everything. “Bonnie and Clyde” at least had the grace to give us a moment of silence after the shooting, so that the fact of death could sink in.

“Hitler” has an incredibly off-key ending (the tone is wrong, even if it’s historically accurate; movies have artistic license to lie, if necessary). Hitler never allowed anyone to smoke, you see, and so the first thing everyone does when they learn he’s dead is . . . light up.

The facts in the movie have been certified as accurate by no less than Hugh Trevor-Roper, who, it is said, should know. I have a rule of thumb about historical movies, and it’s this: Always beware if the producer starts telling you how accurate his facts are. Accuracy is almost always a cop-out in these matters; It means the director and the writers have failed to find an artistically satisfying point of view toward their material. Facts mean nothing compared to truth. And truth, as always, is as elusive as artistry.

This movie resolutely stays outside its characters. Alec Guinness plays Hitler as if they had both been strongly influenced by Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator.” We get the tantrums, the interminable self-praise, the megalomania. Hitler was probably like this, we suppose, but isn’t there a way to arrange this material so we don’t get as bored with him as his senior staff did?

There’s always a problem, as in the case of an extreme personality like Hitler, that a movie will slip over that thin line into comedy. We know what a catastrophe Hitler was to Western civilization, but somehow this isn’t Hitler, it’s Guinness with a moustache, and it’s hard to remember the movie isn’t a parody. “Springtime for Hitler,” from “The Producers,” keeps sneaking in. That happens, for example, in an awkward-funny scene where a city councilman is brought in to marry the loving couple. The councilman, collecting answers for his official marriage license form, asks Hitler: “Are you … Aryan?”

There’s no tragedy in this movie, no sense of the vast scale of suffering outside the bunker. The director does periodically cut to grainy newsreel footage of death and destruction, but this real footage does the opposite of what he expects: Instead of lending credibility to his story, it sabotages it. Guinness and his supporting cast simply cannot stand up to actual World War II footage. The movie becomes an embarrassed fiction.

An example. The movie uses the famous photo of Jews being rounded up in the Warsaw Ghetto. In the foreground there is a little boy, 8 or 9 years old, his hands raised and terror on his face. This photo is one of the most heartbreaking reminders of man’s inhumanity in existence; it belongs with Piccasso’s “Guernica.” Ingmar Bergman used the same photo in “Persona” (along with the notorious TV footage of the street execution of a suspected Viet Cong) to help indicate the moral turmoil within his central character.

But the thing was, Bergman understood that turmoil; had created it; knew why he was using such an emotionally charged image and knew how to direct it. In “Hitler: The Last Ten Days,” the photo (and, indeed, the entire war) are simply exploited for whatever fringe benefits can be extracted. That’s obscene. The movie itself, however, isn’t good enough to be obscene: It’s merely unnecessary.

Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973)

Directed by: Ennio De Concini

Starring: Alec Guinness, Simon Ward, Adolfo Celi, Diane Cilento, Gabriele Ferzetti, Eric Porter, Doris Kunstmann, Joss Ackland, Barbara Jefford, Valerie Gray, Angela Pleasence, Sheila Gish

Screenplay by: Gerhard Boldt, Ennio De Concini, Maria Pia Fusco, Ivan Moffat, Wolfgang Reinhardt

Production Design by: Roy Walker

Cinematography by: Ennio Guarnieri

Film Editing by: Kevin Connor

Costume Design by: Sonia Quemell

Set Decoration by: Michael Lamont

Music by: Mischa Spoliansky

MPAA Rating: None.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: May 2, 1973 (UK), May 9, 1973 (US), August 31, 1973 (Italy)

Views: 366