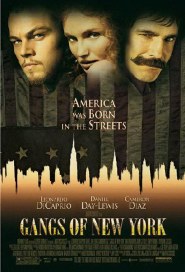

cameron diaz movies

|

|

Chapter 4 - Re-Creating a New York No Longer Exists

With the cast in place, the filmmakers faced their most extraordinary challenge: re-creating a lost New York of tenements, bordellos and saloons, a New York that has never been seen on screen and no longer exists at all outside of books, ghosts and blurry photographs. With an intense devotion to detail, Scorsese fulfilled on his reputation for making things on screen look “more than real.” With the cast in place, the filmmakers faced their most extraordinary challenge: re-creating a lost New York of tenements, bordellos and saloons, a New York that has never been seen on screen and no longer exists at all outside of books, ghosts and blurry photographs. With an intense devotion to detail, Scorsese fulfilled on his reputation for making things on screen look “more than real.”In doing so, the production had a bit of fleeting luck. Recently, a team of archaeologists had begun to dig deep beneath Lower Manhattan to uncover the artifacts and lifestyles of the infamous Five Points. Scorsese and his team utilized this collection of over 850,000 items, ranging from dishes to combs to children’s toys. It was extraordinary timing, for the entire collection (except for 18 items out on loan) was destroyed and lost forever when the World Trade Center 6 Building was partially collapsed by falling debris on September 11, 2001.

It was agreed from the beginning that rather than rely on digital effects, the filmmakers would erect Old New York from scratch, attempting to authentically recapture the look and feel of those days of horse-drawn carts and chaos and corruption in the cobble streets. Says the director: “We created our own world in the spirit of Old New York.”

But they did none of this in New York itself, which over time, built over the dilapidated past so well that it can no longer be found. Instead, the film was shot almost entirely in Rome, at legendary Cinecittá Studios. Scorsese felt at home here because of his close affinity for the cinema of Italy and his high regard for the artistry of Cinecittá’s famed craftsmen and artisans.

Cinecittá had several other attributes to recommend it including a vast back lot where the New York of 1846 and 1863 could be recreated and a massive studio tank for the crucial New York harbor scenes. “I’ve always felt that Cinecittá has a special magic because of all the great films that have been made there,” says Scorsese. “For the many years that I had been thinking about GANGS OF NEW YORK, I always imagined it would be created with an aspect of the Italian artistry that I saw and experienced in Italian films when I was growing up.”

To further excavate the lost world of Old New York, Scorsese hired Luc Sante, author of the acclaimed book Low Life, a riveting modern-day chronicle of Old New York’s dark underbelly, as a technical adviser. “I’m mostly interested in the fringes of society, life in the poor quarters. And this is where a great deal of GANGS OF NEW YORK is set,” says Sante. “I had done five years of research on this period and I was thrilled to be able to put that research in the service of a Martin Scorsese film.”

Sante advised the film team on key particulars of everyday life in the Five Points. Famed for its squalid, overcrowded dwellings and polyglot populaton, as well as its raucous and licentious street life, the Five Points was like an entire universe unto itself. The neighborhood derived its name from the intersection of five downtown streets near a patch of green called Paradise Square. In the New York of today the Five Points would be located northeast of City Hall, essentially on the site of the Federal Court House.

“The Five Points resembled a Wild West town more than a New York City neighborhood of today,” Scorsese observes. And it is that new and fiercely wild urban landscape that Scorsese and team set out to evoke on the screen.

To recreate the Five Points, production designer Dante Ferretti, in his fifth collaboration with Martin Scorsese, constructed a welter of wooden shacks, wooden walkways, brick and cement structures (actually made from fiber glass), then dug dirt roads and laid cobble stone streets across fifteen acres of Cinecittá’s back lot. He erected dozens of structures including the old Brewery exterior, grocery stores (often a euphemism for a bar), a pawnshop, several run-down hotels, the charred remains of a burned-out building, tenement houses and a wharf side saloon.

Other exteriors include a section of New York Harbor, with two great sailing vessels – such as those used to transport immigrants from Ireland to America and ferry Union soldiers to the Civil War – at dock. The team also created a stretch of Lower Broadway, the upper class section of the city at the time, featuring the Tribune Building, P.T. Barnum’s Museum, Delmonico’s Restaurant. They also constructed elegant shops and hotels, as well as several private residences and the neighborhood’s Catholic Church, based on the design of the first St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street. Mandrawn fire engines were recreated based on those found at the Fire Museum in New York.

Among the interiors created at Cinecittá was a major Five Points landmark: the sagging Old Brewery which serves as a makeshift hostel for the constant flow of immigrants, as well as a hideout for the town’s worst criminals. Luc Sante calls this building “a human dump of almost mythic proportions.”

Since no photos or drawings of the building’s interior survive, Ferretti based his designs on a brewery of the same period found in Diderot’s Encyclopie.

Says Martin Scorsese: “We cut the building like slicing a cake to show all of the different rooms in the brewery where people were eking out an existence. There were connecting catwalks and people living in underground tunnel. We show how people lived – barely existed – in these cubby holes.”

Another key interior is Sparrow’s Chinese Pagoda, which functions as a Chinese nightclub, restaurant, gambling casino, brothel, opium den and – even – a theater. The Pagoda is a essentially a dual creation of Scorsese and Ferretti and one of the film’s most elaborate designs.

Based on a fantasized version of an actual structure of the era called the Chinese Assembly Rooms, another building for which no visual record exists, the Pagoda’s central inspiration came from the 1946 Joseph Von Sternberg film “The Shanghai Gesture.”

“Marty didn’t want me to copy the set in the von Sternberg film,” Ferretti notes. “He wanted me to get the feeling of the place, and work from there.”

The Pagoda's focal point is the stage area from which banks of tables fan out and are arranged in clusters on different levels behind ornate railings decorated with gorgons and dragons. Overhead is an enormous wooden chandelier lit with candles; also suspended from the ceiling are bamboo cages containing young women selling themselves to the highest bidder.

To create Satan’s Circus – the bar, social club and butcher shop – that serves as Bill the Butcher’s Native American headquarters, Feretti aimed for claustrophobia and sense of menace. “The main room, long and narrow, makes you feel as if you’re underground. It also reflects the way many of New York’s wooden buildings were constructed in the period, anywhere there was space, without any formal design or architectural blueprint,”

Ferretti says. “In Satan’s Circus, the roots of a big tree growing outside on the street have actually forced their way down through the ceiling over the bar. They stand out like a skeletal hand, something that symbolizes a living death, which was what Marty wanted.”

Creating such sets involved intense research and, when the research reached its limits, the powerful force of imagination. Ferretti drew inspiration from lithographs, prints, books of engravings and daguerreotype photos from the period. He was also influenced by images from a later period, especially the famous New York photographs by Jacob Riis of the poorer sections of the city. Later, Ferretti swung to extremes of opulence in creating Tammany Hall and the luxurious offices of Boss Tweed, with its parquet floors, mahogany desk and leather bound chairs, as well as some fifty canary cages, each one occupied by one or more of the chirping creatures. At the center of the room is a functional Cholera Box, large enough only for a single person: Boss Tweed himself.

In Rome, Ferretti created models and maquettes for all the sets, going over each one carefully with Scorsese. “I always work with models,” Ferretti says. “They are essential because you get three dimensions. When a director looks at a model, I think it helps him to figure out exactly how he wants to shoot.”

As Ferretti and Scorsese settled on the look for each set, carpenters, plasterers, painters, sculptors and iron and tin workers began working round the clock so that 19th century New York, which took a century to build in reality, could be finished in mere months.

Arriving at the studios, and stepping inside the vivid world that was New York City in the 1860s, was a magical, imagination-sparking experience for cast and crew. “When I first saw the sets I was completely blown away. I thought, ‘this can’t be real,’” says Cameron Diaz. “And yet it was. But what really impressed me were the hundreds of extras actually inhabiting the set, going about their lives. I never imagined that it would look so lifelike.”

Luc Sante adds, “Walking around Ferretti’s sets was deeply disorienting, a timemachine experience. Every building looked as if it had been standing since the 18th century. It seemed that Marty had captured what we had set out to do: to be true to the feeling of the period with a poetic accuracy.”

As shooting got under way, everyone also got a sense of the massive scale and scope of the film. There are more than 100 speaking parts in “Gangs of New York,” and before filming was complete, a total of 22,000 background player man-hours would be logged. Many of the background actors appeared in specific roles carried throughout the action of the film. Predominantly Italian, the extras chosen had light hair and fair complexions so they would resemble the Irish. A large group was also recruited from local US Army and Naval bases.

As executive producer Michael Hausman explains, “Although there are one or two scenes in which we do blue screen work and special effects, for the most part what you see on screen is a realistic depiction of what was happening on the set. In that respect, this is traditional, epic filmmaking. The atmosphere was real and it contributed to the overwhelming sense of reality that movie will convey.”

In all Scorsese was delighted by the experience of shooting at Cinecittá. “Usually I work on location in New York, so I found myself kind of spoiled by having the New York City I needed right in front of me at all times. It was much easier to get cross town in Cinecittá that it is in New York City.”

|