When foreigners visit the Netherlands today, certain items seem invariably to stand on their touristic agenda: the Rijksmuseum, Anne Frank’s house, a boat ride through the canals. One of the more remarkable items is a walk through Amsterdam’s red light district, where, on a typical summer evening, in addition to the clientele, thousands of foreigners throng – men, women, couples, even families. Such districts are not usually on the itinerary of respectable tourists, but in Amsterdam a promenade there serves a purpose: foreigners are invited to wonder at the tolerance – or, if you prefer, permissiveness – that prevails in the Netherlands. In the same district but during the daytime, the Amstelkring Museum extends essentially the same invitation.

The museum preserves Our Lord in the Attic, one of the roughly twenty Catholic schuilkerken, or clandestine churches, that operated in Amsterdam in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Nestled within the top floors of a large but unremarkable house named The Hart, Our Lord does not betray its existence to the casual passer-by – it has no tower, no stained-glass windows, no crosses on the outside – and, but for the museum banner that hangs today on the building’s front façade, one could easily pass by it unawares. In its day, though, its existence was an open secret, like that of the other schuilkerken. Its discreet architecture fooled no one, but did help to reconcile the formal illegality of Catholic worship with its actual prevalence. Today, the museum’s guidebook (English version) presents the church as ‘a token of the liberalism of the mercantile Dutch in an age of intolerance’.

Around the world, Dutch society is famous for its tolerance, which extends to drug use, alternate lifestyles, and other matters about which most industrial lands feel a deep ambivalence. But whence comes that tolerance, that ‘liberalism’? The guidebook hints at two answers. One is that tolerance promotes commerce and thus is profitable; the other is that the Dutch are simply a ‘liberal’, that is, tolerant, people. Tolerance is represented as smart economics, but also as a national trait – a virtue by most people’s account, a vice by others’, but either way as something rooted in the history, customs, and very character of the Dutch people. The Dutch, in other words, do not just practise tolerance: by their own account and others’, they are tolerant; it is considered one of their defining characteristics.

This is nothing new: ‘Dutch’ tolerance was already proverbial in the Golden Age, though the tolerance then under discussion extended only to religions. Indeed, as early as the sixteenth century, in the crucible of their Revolt against Spain, the Dutch – with Hollanders in the vanguard – began to define themselves as an especially, even uniquely tolerant people. That identity was cemented in the Golden Age, when Calvinists, Catholics, Mennonites, and a host of other religious groups lived peacefully alongside one another. In our own century, the same notion of Dutchness has expanded beyond the religious, just as the concept of tolerance itself, rooted in the religious dilemmas of early modern Europe, has come to be applied to all forms of ‘otherness’.

Logically, the argument that the Dutch practise tolerance because they are tolerant is nothing but a tautology, unless one believes in national character as an autonomous, causal force in history, which few scholars do today. As a cultural construct, though, the argument continues to function as a powerful expression of national identity.

In that capacity it provides a standard of behaviour against which the Dutch judge their society and government – severely sometimes, for example as concerns policy towards the ethnic minorities come in recent decades to live in the Netherlands. It also provides a framework for the interpretation of Dutch history. But here the problems begin, for the essentialising of ‘Dutch’ tolerance has for centuries involved mythologising, encouraged anachronism, and served partisan causes. In this way it has long obscured our understanding of religious life in the Dutch Republic. Today it does the same, but in a twofold manner: not just by propagating but also by provoking reactions, some of them exaggerated, against such mythologising, anachronism, and partisanship.

The mythologising began early. In the sixteenth century, Netherlanders justified their Revolt against Spain most frequently as a conservative action in defence of their historic ‘privileges’, or ‘liberties’. As Juliaan Woltjer has pointed out, only some of those privileges had a firm basis in law or fact, and what they entailed was not always crystal clear. Even the famous jus de non evocando, perhaps the most frequently cited privilege of all, was capable of varying constructions: while most people agreed that it guaranteed that a burgher accused of a crime would not be tried by a court outside his province, opinions differed as to whether it assigned to local municipal courts sole and final jurisdiction in such cases.

Either way, the privilege conjured up a time when cities and provinces had enjoyed judicial autonomy, and therein lay the true power of the privileges generally: to evoke an idealised past against which the present could be judged. However vague their positive content, no one mistook the privileges’ negative import as an indictment of, and justification for resistance to, the Habsburg government’s unwelcome initiatives and innovations. Foremost among the latter were the efforts of Philip II to introduce what the Dutch, with great effect if little accuracy, called the ‘Spanish Inquisition’: an institutional structure for suppressing Protestantism, reforming the Catholic Church, and imposing Tridentine orthodoxy on the people of the Netherlands. Such a programme entailed gewetensdwang, the forcing of consciences, on a massive scale.

But if gewetensdwang was new and contrary to the privileges, was its opposite, freedom of conscience, then part of a hallowed past? That was at least the vague implication, made more plausible by the fact that believers in the old Catholic faith as well as converts to Protestantism resisted the government’s religious policies. Still, given that the variety of religious beliefs spawned by the Reformation was scarcely older than the placards outlawing them, it took some legerdemain to construe the privileges as guarantors of freedom of conscience. Nevertheless, a few writers of the period did so explicitly. Two anonymous pamphlets dating from 1579 appealed to the Joyous Entry of Brabant, the oath taken since 1356 by each new duke of Brabant by which he swore to ‘do no violence or abuse to any person in any manner’.

This word in any manner, expressly highlighted [wtstaende] in the Joyous Entry, excludes any kind of violence or abuse, be it to property, body, or soul, so that the king is bound by virtue of the Joyous Entry to leave every person in possession of their freedom, not only of property or body but also of soul, that is, of conscience.

That this interpretation might seem rather far-fetched did not escape the author of either pamphlet, but in its support both cited a treaty between Brabant and Flanders concluded in 1339 (and published, as a timely reminder, in 1576), in which the vague phrase ‘in any manner’ is glossed to mean ‘in soul, body, or property’. Contrary to what some people think, says one of the pamphlets, it is a wonder to see ‘how careful our ancestors always were to preserve and to retain the enjoyment of this right’, freedom of conscience, ‘which until the arrival of the Inquisition we always enjoyed’. Even more remarkably, both pamphlets go on to equate freedom of conscience explicitly with freedom of worship. Not even the Inquisition could stop people from believing what they wished; the freedom which it took from us, therefore (so the argument went), must have been the right to profess our beliefs publicly and to worship God in accordance with them.

Thus by anachronism religious tolerance took on the aura of an ancient custom. Once gained, that aura did not readily fade. Eighteen years later, Cornelis Pieterszoon Hooft, burgomaster of Amsterdam, thought it entirely plausible to tell his fellow regents that it was ‘in accordance with the ancient manner of governing this land and this city’ that they ‘bear with each others’ mistakes in matters of faith and not disturb any person on account of religion’. In 1659, Pieter de la Court represented what he perceived as a decline in religious tolerance as a departure from the ‘original maxims’ of his province.

Some of its apologists, however, represented the Revolt as a fight not just for specific ‘freedoms’, plural, but for ‘freedom’, singular and abstract. Jacob van Wesembeeke, Pensionary of Antwerp, played a crucial role in developing this argument. In 1566 he described the people of the Netherlands as ‘having always been not just lovers, in the manner common to other peoples, but special and extremely ardent advocates, observers, and defenders’ of their ‘ancient liberty and freedom’. William of Orange, for whom Wesembeeke worked for a time as propagandist, took up the theme, characterising Netherlanders ‘as exceptional lovers and advocates of their liberty and enemies of all violence and oppression’. Both men attributed a religious dimension to the liberty so cherished, Wesembeeke speaking reverently, for example, of the ‘anchienne liberté au spirituel’ of the Netherlands. Thus the Dutch devotion to religious freedom was given a basis in national character as well as custom.

That character took on a sharper profile over the course of the Revolt, especially after the return of the southern provinces to the Spanish fold. Northerners – Hollanders in particular – increasingly appropriated to themselves the special love of freedom once more widely conceded. One way they did so was through the myth of the Batavians, which had been circulating since the 1510s but gained enormous cultural prominence from the 1580s. Histories, dramas, and paintings celebrated this ancient Germanic tribe, known chiefly from the writings of Tacitus, as ancestors of the contemporary Hollanders and founders of their polity. Virtuous, industrious, pious, and clean, paragons of a simple decency, the Batavians appear in works like Hugo Grotius’ Liber de Antiquitate Reipublicae Batavicae (1610) above all as fiercely independent.

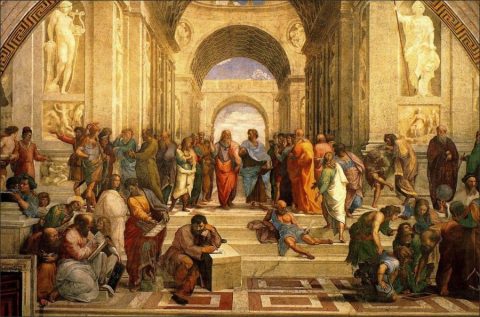

The tale of their struggle for autonomy from Rome was taken to prefigure the Hollanders’ own struggle with Spain and predict its happy outcome. In another work, the Parallelon Rerum-Publicarum Liber Tertius (written around 1601), Grotius compared the formerly Batavian, now Hollandic people to the ancient Athenians and Romans. The former emerge as superior in almost every respect to the paragons of civilisation venerated by Renaissance Europe. This experiment in comparative ethnology represents the Revolt as a fight by the Hollanders ‘for the freedom of their souls’ as well as of their bodies, and exults in the Hollanders’ combination of piety and tolerance.