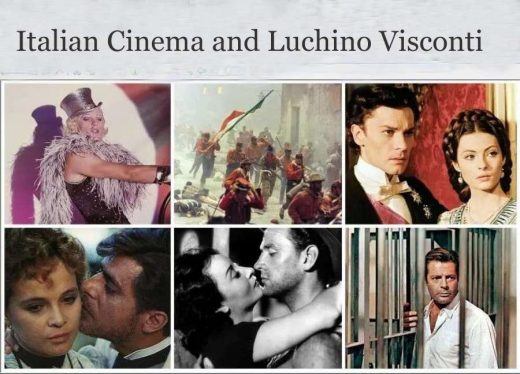

A filmography from neo-realism to decadence: Luchino Visconti.

Italian director Luchino Visconti (1906-1976), nourished by music, opera, painting, history and literature, is one of the most “aesthetic” directors of cinema. Visconti, who was raised in Italian Neorealism but developed his own style in a short time, is a director who turned his back on the winds of his time and followed his own aesthetic tendencies and obsessions throughout his life.

Luchino Visconti, the epic poet of a magnificent aesthetics of decadence, destructive passions, corruption and perversion, beauty and call to death, is on the big screen once again with the cooperation of Istanbul Italian Cultural Center. Within the scope of the retrospective, all of the director’s feature films, except Vaghe Stelle dell’Orsa (1965), will meet the audience at the Kadıköy Municipality Cinematheque/Cinema House Onat Kutlar Cinema Hall during May and June.

Building blocks of Italian neo-realism

The director’s first film, Ossessione, made in 1942, adapted from the novel The Postman Rings Twice, is considered one of the first and pioneering films of the New Realism movement. The Earth is Shaking (La Terra Trema, 1948), which tells the collapse of the Valastro family, who sought to become individually independent after their resistance against the merchants who exploited them failed, is one of the masterpieces of the movement.

Criticism of the bourgeoisie

While Anna Magnani worked wonders in Bellissima (1951), the story of a working-class woman who wants to make a star out of her little daughter, being seduced by the glittering entertainment culture of the bourgeoisie and subsequently disappointed, Senso (1951), which declared the director’s break with neorealism and took place during the process of national unity of Italy. 1954) is the film in which Visconti first encountered the themes of historical collapse and corruption. White Nights (Le notti bianche, 1957) is a testament to the director’s admiration for Dostoyevsky and the contrary child of his filmography.

Alain Delon, Burt Lancaster and Marcello Mastroianni on stage

The 1960 film Enemy Brothers (Rocco e i suoi fratelli), an epic narrative about social change with the intensity and depth of a 19th century novel, in which characters represent historical and social trends, led to a serious leap in Visconti’s international fame.

The Leopard (Il Gattopardo, 1963) won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, further cementing the director’s reputation. The film, starring Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon and Claudia Cardianale, is a narrative of change and transformation full of historical characters. As a member of a dying class, the director reveals for the first time his silent and aesthetic sadness for the collapse of aristocratic values.

The Stranger (Lo Straniero, 1967), adapted from Albert Camus’s existential novel of the same name, is the story of the terrifying indifference of Mersault (Mastroianni), who is sentenced to death at the trial for murder, not for the crime he committed but for his lack of empathy, and even for his attitude of refusing to pretend to feel empathy.

German Trilogy

In the first film of the German Trilogy, The Damned (La caduta degli dei, 1968), in which he never refrains from going to extremes, the director prefers an expressionist aesthetic to a realism full of real characters. With his 1971 film Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia), he returns to his beloved author Thomas Mann and pursues examining one of his favorite themes, the relationship between death and beauty.

In the last film of the trilogy, Ludwig (1973), he was an art and aesthetic enthusiast who could never adapt to his position, an eccentric homosexual, and was dethroned on the grounds that he was “crazy” by a conspiracy of the Bavarian government. He uses Ludwig’s reign as a historical context for the idea of decadence, trying to rationally frame his nostalgic/aesthetic pleasure and intense interest in decadence.

Visconti’s farewell

In Family Table (Gruppo di famiglia in un interno, 1974), an esthete who devoted himself to painting and music as a result of the disappointment he experienced while being an expert in positive sciences and lives an isolated life in his small monastery, while waiting for the day he will die among dead objects, experiences almost the exact opposite of everything he believes and loves.

It is about the disruption of peace by a representative family. In his farewell film Innocent (L’Innocente, 1976), which is a cool-headed criticism of all existential philosophical schools that glorify “will”, starting from Nietzsche, Visconti demonstrates sharply and strikingly how our animalistic instincts limit our voluntary choices and self-control claims. .

Views: 355