Perhaps no director in the history of cinema has lived in such harmony with his art as Francois Truffaut. Truffaut took a radical stance that eliminated the line between his autobiography and the scripts of his films, and argued passionately that film art should start from the artist’s own life.

Throughout his career, in which he made more than 20 films, Truffaut became one of the most important representatives of the New Wave movement in cinema, of which he formed the foundations. Truffaut’s passionate and personal approach to cinema was shaped by the environment in which he was born and raised.

Shoot the Pianist (Tirez Sur le Pianiste, 1960)

The Liberating Camera

When the long shot is out of control of the story, a liberating experience begins for those in the frame. It is true; François Truffaut has many films that can be considered – at least on paper – within the scope of genre cinema. However, in Truffaut’s films, genre cinema patterns turn into a tool in which cinephilia is reflected, rather than making the moving image subservient to the story. The director’s mentor, film theorist André Bazin, gives the formula for Truffaut’s cinema when he talks about how the long shot allows objects and actors to exist on their own.

Fahrenheit 451, 1966)

Literature

At first glance, it may seem surprising that a director who is looking for moments when cinema is freed from the yoke of plot has included literary references so enthusiastically. Truffaut used the Balzac motif in many of his films, especially The 400 Coups (Les Quatre Cents Coups, 1959), Two English Girls (Les Deux Anglaises et le Continent, 1971), Jules and Jim (Jules et Jim, 1962) and Fahrenheit 451 (1966).

He often brings the inspiration he draws from literature to the screen in adaptations such as (1966). However, his approach goes beyond simply transferring the plot of the novel to the screen; The director feeds on the nurturing contrast between literature and cinema. Performances are more than the flesh and blood of novel characters; the unfolding of the story no longer depends only on the cause-effect relationship on paper. By invalidating the limits of familiar adaptations, Truffaut moves towards the real richness of the literature-cinema relationship.

Les Quatre Cents Coups, 1959)

Jean-Pierre Leaud / Antoine Doinel

In Olivier Assayas’s satire Irma Vep (1996), which is about the transformation in French cinema, the presence of Jean-Pierre Leaud was enough to create New Wave associations in the audience. The actor, who played François Truffaut’s alter-ego Antoine Doinel from 400 Blows until the end of his career, became the icon of the New Wave movement due to this position.

The basis of this relationship, which cannot be explained by just being the ‘favorite actor’, is Leaud’s ironic approach to his character, and therefore his performance that frees him from his bonds. Leaud is the complement of Truffaut’s cinematic attitude with his alienating position within the story, rather than Truffaut’s reflection on the screen.

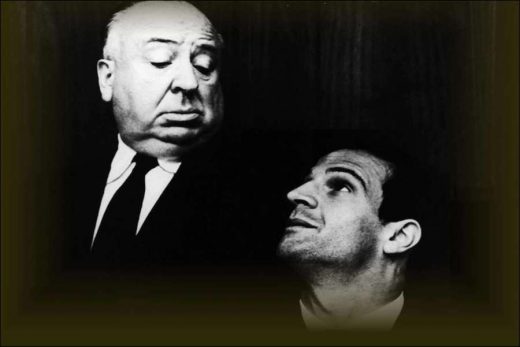

Hitchcock and Truffaut

Alfred Hitchcock

Thinking with the camera allows the conventional forms of cinematography, story and time system to lose their validity in Truffaut’s cinema. For example, the long shot ceases to be a connotation of serenity and tranquility. Time neither progresses in a straight line nor is it just a disintegration of this line. The sudden freezing frames do not indicate the end of the story, but the clarity that follows.

Of course, none of these are techniques that the director took directly from Hitchcock, whom he considered his mentor, but they are extensions of his method of using the camera as an extension of his mind, in Truffaut’s practice. By publishing his long interview with his master about the craft in 1967, he removed this admiration relationship from a personal level and caused the entire cinema world to look at Hitchcock with a different eye.

Jules et Jim, 1962

Female Characters

The interest of his New Wave peers, who, like him, were cinema writers for Cahiers du Cinéma magazine in his youth, towards Hollywood craftsmen and genre cinema, has an important place in François Truffaut’s oeuvre. However, in Truffaut, who uses genre films as a disciplinary tool that will reinforce his creativity rather than a restrictive guide, women are in a very different place than they were in this source of inspiration.

Its mysterious aspects are not coded as a threat, but rather arouse admiration as an element that undermines the dualities on which the story is based. A clear example of this attitude is the use of the dolly zoom effect in Jules and Jim, inherited from Hitchcock cinema, which distorts visual perception and serves to evoke danger: This technique is used to convey the two male characters’ first sight of the female bust, which they will find reflected in Catherine, with whom they are in love. However, the rest of the story refrains from interpreting this smile as “poisonous”, despite all its tragic nature.

Views: 273