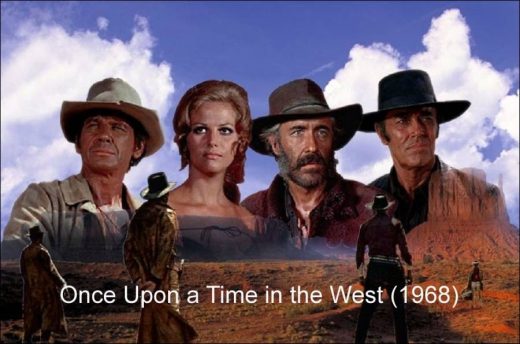

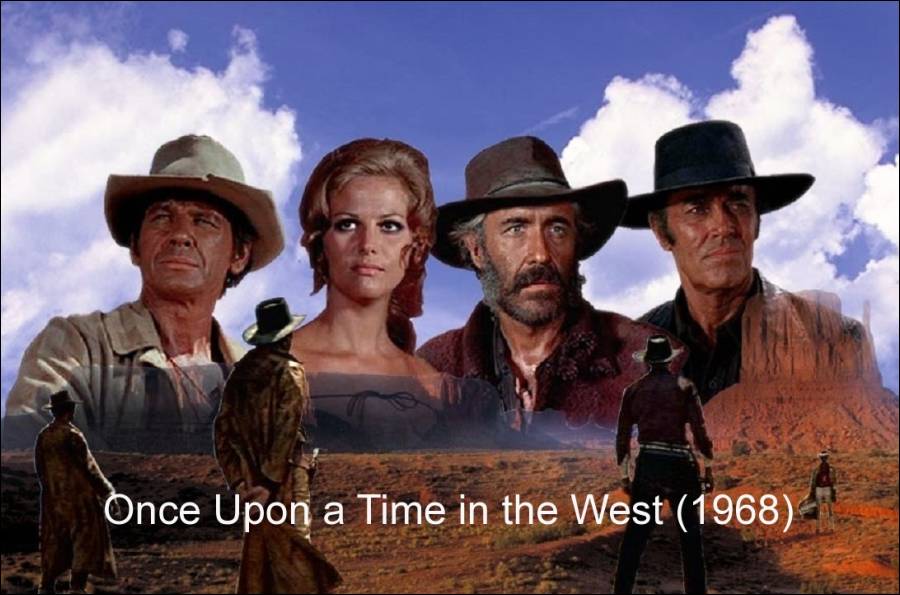

In the middle of Sergio Leone’s 1968 film Once Upon a Time in the West, Charles Bronson’s character Harmonica wins an auction for a farm for $5,000. However, it turns out that he will make the payment by handing over Cheyenne, with a $5,000 bounty on his head, to law enforcement.

Cheyenne, played by Jason Robards, likened this betrayal to the betrayal of Jesus, saying, “You got $4970 more than Judas.” Awake Harmonica snaps: “Didn’t there be such a thing as dollars back then?” Robards’ response is unforgettable: “There were bastards though”. This short dialogue is the essence of Spaghetti Western for me.

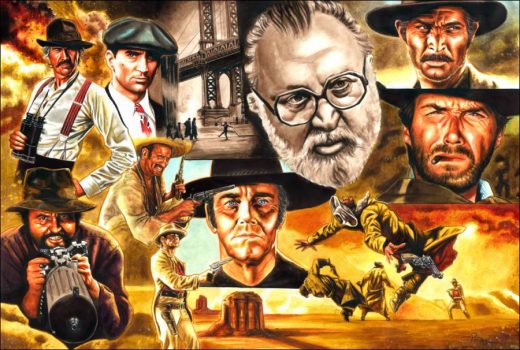

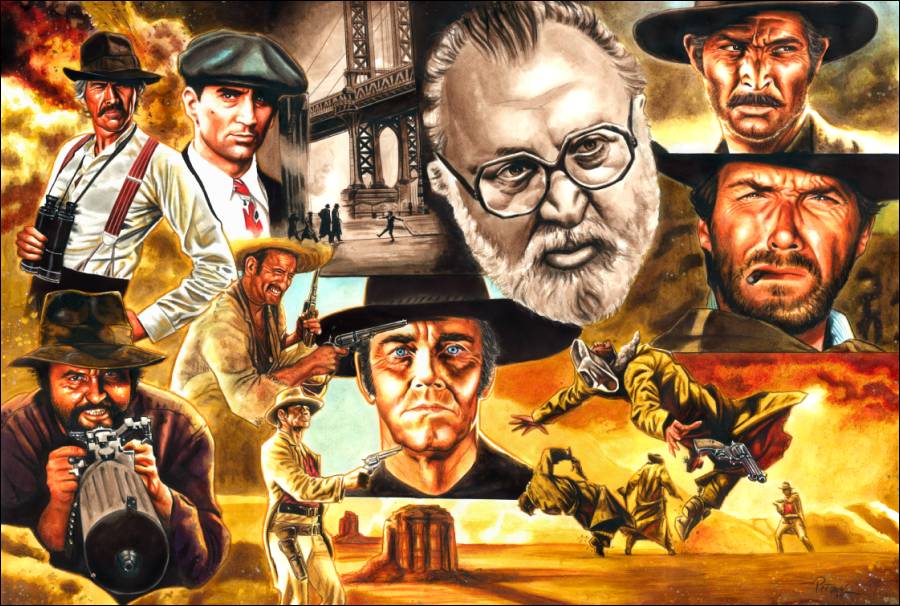

However, it would be useful to add here the more formal definition of our master Rekin Teksoy in the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Cinematic Terms, which is considered sacred to our profession: “The name given to western films shot in Italy, inspired by the Italian national dish, spaghetti (pasta).” We are not going to cite the “Spaghetti Western” articleas it is (anyone should definitely find and read it) but to cite a few details, Sergio Leone used the pseudonym Bob Robertson in his first western, not his own name, that he is new to the western genre. we can list that the filmmaker, who gives a visuality, has developed a style based on the tense episodes he created, especially by making use of very close plans.

Born in Rome in 1929, Sergio Leone’s father was Vincenzo Leone, one of the pioneers of Italian cinema, and his mother was Edvige Valcarenghi, one of the actors of that period. In a sense, he was born into the cinema. In fact, Vincenzo Leone was actually the person who shot the first western movie (Indian Vampire) in Italy in 1913.

Long story short, Sergio was familiar with film sets from an early age, and by the time he was 18 he was already leaving his law university to start working in the industry. He was in the 40s, where he worked as assistant director or second team director with names such as Vittorio De Sica, Carmine Gallone, Mario Camerini, Mario Bonnard, Mervyn LeRoy, Mario Soldati, Robert Wise, Fred Zinneman, Robert Aldrich and William Wyler. It would not be wrong to say that it was the 50s.

It is even known that some important parts of that famous race scene in Ben-Hur were shot by Sergio Leone. In other words, Leone was cooked on the counter of both Italian cinema and American cinema, as it was cheaper for Hollywood to shoot in Cinecittà at that time. Think about it, you are working on a great classic like Bicycle Thieves on one side, and on another big production like Ben-Hur on the other side. As a matter of fact, Leone continued to film and passed away at the age of 60, leaving one of the deepest traces that can be left. But there is still time there…

His popularity became his curse

Speaking of traces, is there a second filmmaker in the history of cinema who left such a deep mark by making so few films? I’m guessing one of the first names that comes to mind is Quentin Tarantino (Hazrat made nine movies and has been saying he’s quitting in the tenth for years) but he says very clearly that Tarantino wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for Leone; at least it would be someone other than today.

In a way, it wouldn’t be wrong to include Leone in the list of filmmakers who left a big impression with a small number of films such as Kubrick and Tarkovsky; with one difference, his name has always been mentioned in more popular movies than them. As a matter of fact, this popularity is responsible for its somewhat unfair place in the history of cinema. If anyone is curious, look at the list of the handful of awards he has won, the most obvious sign that he is not being taken seriously is there.

Leone’s first film, Rhodes Monster, which was his first film, was one of the historical productions that was the locomotive of Italian cinema in those years and was referred to as the “sword and sandal” film, and Leone would later say that he shot this film only to pay for the honeymoon. Therefore, it would not be wrong to say that his career that will make him write in the history of cinema started with the western titled For a Handful of Dollars, which he shot in 1964.

Sergio Leone, who changed not only his own name but also the names of leading actors Gian Maria Volonte (Johnny Wels) and composer Ennio Morricone (Dan Savio), probably because he wanted the film to be thought of as a true American Western, had a production budget of approximately $200,000. finished his first Western movie in a week. The movie was actually like a copy of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo.

“Kurosawa had shot ‘Yojimbo’ based on Hammett’s novel, so I tried to bring the story back to its homeland by shooting a western,” Leone would say. It is said that a handful of spectators also attended the film when it was first screened in a movie theater in Florence in August 1964 for a Few Dollars.

Knowing very well that this box office failure was the kiss of death for the movie, for which no advertisement was made for the promotion, Leone grudgingly returns to Rome, but hears from the operator of the cinema that ticket sales have doubled on Sunday. On Tuesday, the audience can no longer find tickets. Thanks to the newspaper Whisper, the film not only became the highest-grossing film of that year, but also broke the record by making the highest box office among all western films shown in Italy until then. Of course, right after Leone, Clint Eastwood and Ennio Morricone had a significant share in this success of the film.

From TV actor to world star

Don’t look, Leone has two expressions for him: “As an actor; with or without a hat”; After Clint Eastwood’s Dollar Trilogy, he was very upset because he didn’t want to act in Once Upon a Time in the West, and that’s why he uttered these words, otherwise the American actor was of course of great importance in Leone’s career. Of course, the opposite is also true; It is difficult to predict what kind of CV Clint Eastwood would have had without Leone’s films, but it is not at all predictable that he would not be able to pursue such a brilliant career. As a matter of fact, he himself must have been aware of this, as Eastwood would write: “To Sergio and Don” (for Sergio and Don) when dedicating his 1992 film Unforgiven to two names who had a great influence on his career.

As you know, Eastwood wasn’t Sergio Leone’s first choice for the unnamed stranger in the movie. He said that Henry Fonda, the actor he really wanted, was passed by the production company because it would be too expensive; We know that many actors such as Charles Bronson, Henry Silva, Rory Calhoun and James Coburn also rejected the script. Richard Harrison, one of the actors who rejected the role, recommended Eastwood.

It is not known whether he hit his head on the stones afterwards, but thanks to him, Leone and Eastwood came together and they easily agreed on the idea of going to Italy to shoot a movie for Eastwood, who was trying to get rid of the TV market in the USA. The result was, of course, a legend that would go down in cinema history and turn into a series of not one but three films.

Above all, it was this collaboration that turned the spaghetti western genre into a real trend; Maybe it wasn’t the first western filmed in Italy, For A Fistful Dollars, but it was undoubtedly the most successful, and almost everyone who came after it would try to imitate it or to change it, to surpass it, to make one forget it. Still, it would be Leone who did it best. The “mysterious stranger” character, created by him and portrayed by Eastwood, was of course the prototype of a protagonist (in fact, a complete anti-hero) to be imitated in almost all spaghetti westerns.

Anything can happen in any moment

“In John Ford’s films, when a character looks out the window, he sees his immense future lying before him; In my films, when a character looks out the window, he is always afraid of getting a bullet in the middle of his forehead,” said Sergio Leone in an interview.

In what he says, we not only see the difference between classic westerns and spaghetti westerns, but also one of the key concepts of Leone’s cinema: suspense. Indeed, a master of suspense, Leone somehow manages to keep the tension high even on the most “calm” stage. In his films, the audience can never get away from the feeling that anything can happen at any moment. Maybe the only element that will balance the tension and relax the audience is the humor that comes into play once in a while.

Italian writer Alberto Moravia says in one of his articles, “Hollywood westerns are built on myth, spaghetti westerns are myths of myths”. In addition, we can say that the most important difference of Spaghetti westerns is that almost everything in classic American westerns is turned upside down. So there are no heroes, there are anti-heroes.

We do not have shaved, handsome, decent-looking cowboys who are the epitome of morality, but rather messy hair and beard (this was also the case for Eastwood to some extent, we don’t see him shaved in the Dollar trilogy), crooks, scumbags, and foul-mouthed types. Alliances are fleeting, friendships are unreliable, and when it comes to money (which is always money), selling is inevitable; The quickest shooter wins.

Of course, the element of violence is much more prominent in these films and the subject is usually shaped around themes such as betrayal, reckoning, and revenge. Maybe it’s worth remembering this: These films were shot at a time when it was believed that the era of the “good” guys representing the law in Italy, which was defeated by the Second World War and suffered for years in the grip of fascism before that, was made and the “hero” prototype was a little “dirty”. It didn’t seem wrong to anyone. Neither “good” was completely good, nor “bad” was all bad…

Everyone was competing with each other in immorality, and everything was ultimately decided by the guns. Or, in Leone’s words: “Probably the best western writer was Homer. The characters he wrote were never all good or all bad. They were half and half, like all people. I’m just like Diogenes, looking for those amazing people with my flashlight. I haven’t found it yet.”

Morricone factor

One of the most impressive collaborations in the history of cinema is undoubtedly the partnership between Leone and Morricone. The thing is, it’s almost impossible to think of Sergio Leone’s films without Morricone’s music. Going further, Morricone’s music has been almost as influential as Leone’s framing, characters, and themes when it comes to spaghetti westerns.

The elements that Leone used most when building tension were music and sound. He often dreamed of having the music ready before the movie (which he failed to achieve in the early films, but in some scenes of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and nearly all of Once Upon a Time in the West), preferring to surrender his scenes to the rhythm of the music rather than dialogue. Morricone, who grasped his style very quickly, did a great job with crescendos, repetitive themes, instruments that he added and removed according to the characters, and made the music a dominant element by saving it from being a secondary element accompanying the images in the background. After all, while the western is an American invention, opera is first and foremost an Italian art.

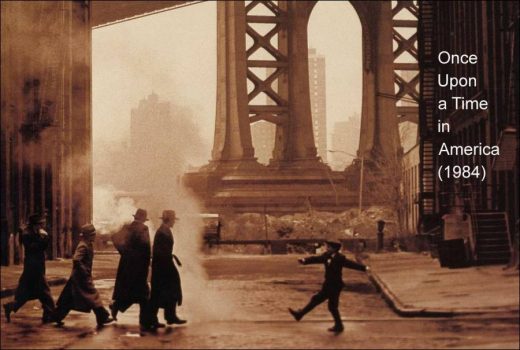

Opus magnum: Once Upon a Time in America

The last film left to us by Sergio Leone, Once Upon a Time in America, met with the audience as part of the Istanbul Film Festival years ago, and the film was interrupted twice due to its long duration; There will be those who remember. Leone, who died at a very early age (he was only 60 when he died), had waited for many years to find money to shoot this movie, and even refused to shoot The Godfather / The Father, according to rumors, because the plot was too similar.

A 4-hour mafia epic emerged when Leone, who had the whole movie planned in his mind, finally realized Once Upon a Time in America thanks to producer Arnon Milchan, whom he met by chance in Cannes. Unfortunately, things did not go as he had hoped. While releasing the movie in the USA, they turned it into a bird and played with its editing a lot; In Leone’s words, they “destroyed its essence”. According to many, Leone’s health has always gone downhill after this incident. Until 1989, when he died.

Leone always looked to the past in his films (it could go back to the 60s at most) and although he did not speak any English, except for his first film (which actually saved his life, for those who are curious; a tip: Charles Manson) he has always been to America. told. Of course, what he told was something much deeper than America, probably an America that he distilled from his own childhood, from the movies he watched, and he was looking into the depths of his own soul, telling the tales he had heard or not listened to in those years.

If he had lived, maybe he would have made a movie that looked east (but still tells the past) for the first time. The book The 900 Days, which he read in 1969 and plans to shoot ever since, was about the siege of Leningrad and probably required a $100 million budget in 80s money. Just a few months before his death, he announced at a press conference that he had made a deal for the film, but it did not happen, the project turned into one of the famous unfinished legends of the history of cinema.

Sergio Leone passed away after a heart attack on April 30, 1989. Near his death, rumor has it that he went to the Pratica de Mare cemetery in Rome with a friend and chose a burial place with a sea view and a shadow. When his friend said, “But someone is already lying there,” his response, befitting a director, was: “We’ll move him elsewhere.”

Views: 420