Vincent Van Gogh found in Millet the basis of a primitive popular art, models for portraits of humanity. He made the gravity of Millet graver, I might almost say more Lutheran. The ancient Greek spirit which breathes from many of Millet’s soft pencil drawings like a natural sound, gives place in him to a gigantic instinct, in relation to which the Millet form appears only as as oftening element.

There is nothing classical about him; he reminds us rather of the early Gothic stone masons; the technique of his drawings is that of the old wood-carvers; some of his faces look as if they had been cut with a blunt knife in hard wood. The ugliness of his personages, the “mangeurs de pommesde terre,” carries the primitive ruggedness of the older painters to the region of the colossal, where it occasionally resembles materialised phantoms of horror.

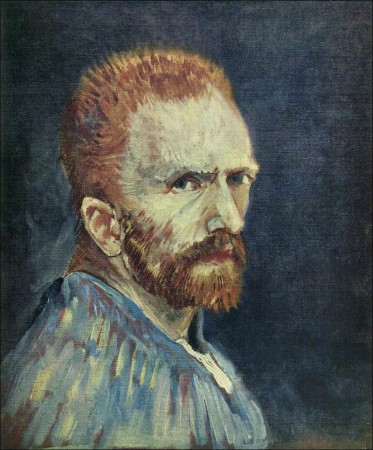

Heprojected such things as La Berceuse not for amateurs, but for common folks, and it was one of his–all too natural–disappointments, that no peasant would give himself up to sitting. In his painted portraits, the hard wood of the drawingsseems sometimes to be blent with gleaming metal. Schuffenecker owns the most masterly of his portraits of himself.

No-one who has seen this tremendous headwith the square forehead, the staring eyes and despairing jaw can ever forget it. It is so full of a terrible grandeur of line, color, and psychology, that it takes away one’s breath, and it is hard to know whether one is repelled by its monstrousexaggeration of beauty, or by the lurking madness in the head that conceived it.

Van Gogh’s self-destruction in the cause of artistic expression is tragic, because it was a natural sacrifice, not a self-defilement, the act of a perfectly healthy consciousness, shattered by insufficient physical powers of resistance. “The more ill I am, the more of an artist do I become,” he writes, with no thoughts of verse joys in his mind. He records the same simple fact with which Delacroix reckoned, and Rembrandt, “the old wounded lion with a cloth round his head,still grasping his palette.”

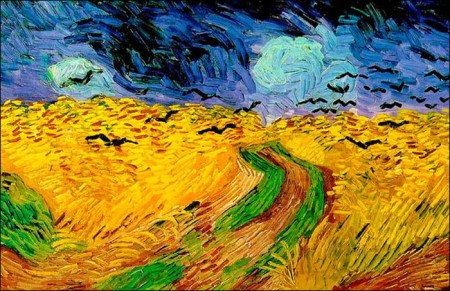

The tragic result was inevitable, because it fulfilled a natural doom. The only means by which he could escape despair, retain his self-respect, and repay the devotion of the brother who had spent so much on canvas and colors was, to make constant progress, to loosen more and more the slenderthreads that bound his individuality to a failing body, and penetrate ever more deeply into the mystery that dazzles the eyes, to give bodily substance to theartistic soul, even when it was parting soul and body.

It was heroism, becausethe result was hardly doubtful to him, a peasant’s heroism, because it went straighton its way without any dramatic gesture, simply and naturally. In one of hisletters Vincent speaks of a worthy fellow who died for lack of a proper doctor: “He bore it quietly and reasonably, only saying: ‘It is a pity I can’t have anyother doctor.’ He died with a shrug of the shoulders that I shall never forget.”

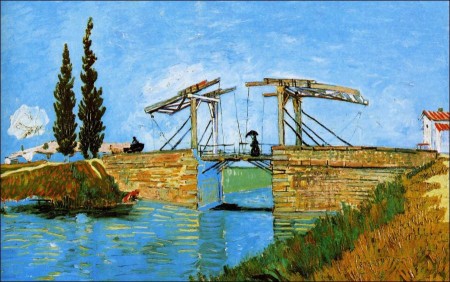

In some such fashion Vincent’s death must be explained. Even in the early days at Arles, when Gauguin was with him, be once threatened to cast off the weary flesh. He came to himself again, and went voluntarily to the Arles asylum, where he painted some wonderful things, among others the Schuffenecker portrait of himself, the cloistered garden of the asylum with the splendid flower-beds (belong shying to Hessel), and some beautiful flower-pieces.

In his letters to Theo he revealsa marvellous memory, clinging to childish recollections, as if to interpose his home between himself and the strange power that sought his life; he recovered so far, that he went to Saint Rémy, to find a new field of activity there. But his brother was in trouble, and when Vincent came to visit him in Paris he recognised his own danger, and looked about him for help. He found it in Dr. Gachet.

Gachet, who still pursues his avocation and his art robustly, had a comfortable, hospitable house at Auvers-sur-Oise, near Valmandois, where Daumier spent his lastyears of blindness. Daubigny painted there, Cézanne came thither in 1880 at Gachet’s recommendation, and lived there for several years, painting many finethings; to many others the happy land and the old artist-doctor’s table were a solace. Even Van Gogh seemed to have painted himself into health at Auvers. He came in the middle of 1889.

His Auvers pictures have not, of course, the intoxicating richness of strong colour revealed to him by the south; but on the other hand, he achieved an unprecedented development in his play of line. His own portrait and his portrait of Gachet are purely rhythmic works, quite free from hardness, marked by a perfectly conscious application of his unrivalled talent for decorative tasks. In the roses, and in the arrangement of chestnut leaves and blossoms, a happy harmonious spirit seems to be weaving its beautiful dreams, remote from all dramatic violence.

Visits: 59